Cambodia's ruling party spokesman has dismissed a report suggesting Prime Minister Hun Sen artificially inflated the number of "likes" on his Facebook page, but observers say the claim that he may have paid for his online popularity is damaging.

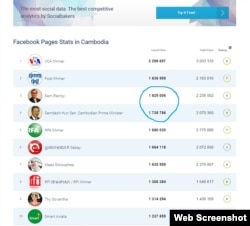

Just days ago, Hun Sen announced he had reached 3 million likes on the renowned social-media platform, joking that his popularity made him "the Facebook Prime Minister." While he joined Facebook only some six months ago, he appeared to have overtaken opposition leader Sam Rainsy's 2.2 million likes. Rainsy has been on Facebook for at least five years.

However, in a Wednesday report citing figures from media analytics company socialbakers.com, The Phnom Penh Post newspaper said that only about 20 percent of Hun Sen's recently added fans were Cambodia-based users.

Many of the likes came from countries whose citizens would have little reason to support Cambodia's long-term ruler. The report also said a great number of likes posted in the past 30 days came from India, the Philippines, Burma, Indonesia, Turkey and Mexico, raising the possibility that the prime minister had been buying his popularity on the site.

‘Likes’ vs. popularity

Chok Sopheap, executive director at the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, said she was "surprised" by the report, adding that it raises concerns about the transparency of Facebook's "likes" function, which has been used by Cambodian politicians to compete for popularity.

"The report is a wake-up call for social media users concerning the techniques to make gains in terms of popularity," said Chok Sopheap. "I believe some politicians and institutions have used money to broadcast themselves."

However, she added, a politician's popularity shouldn't be judged by social media activity alone, but by their effectiveness as public officials.

"The real concern is that the users themselves have to understand that the number of likes they gain on Facebook does not [accurately] reflect their popularity or [whether] there's full support for them," Sopheap said.

Nget Moses, head of the Internet technology department at Phnom Penh-based CENTRAL, an online rights advocacy group, explained that Facebook users could pay money to advertise their Facebook posts or page, a mechanism known as "boosting."

"We cannot use money to buy likes," he told VOA Khmer. "However, what we can do is pay money to boost our page or posts in order to reach a wider audience, as well as select where the page or the posts can be most seen. The location will imply where we obtain the most number of likes from, and it means that is the country where the page or the post can be seen the most. This appears on the account of the users."

Support for prime minister

The expert suggested that the administrators of Prime Minister Hun Sen's Facebook Page could release reports and the data behind the page for the sake of accountability and transparency.

Sok Eysan, spokesman for the ruling Cambodian People's Party, dismissed the report, insisting that the prime minister had no reason to artificially inflate his online popularity.

"We don't believe it, and we cannot accept what's spoken informally outside," he said. "Some alleged that the Cambodian government even hired people to like. I just want to say that there's no use in having other people overseas like the page because there is not much benefit borne out of that.

"The main concern is the interest of the Cambodian people," he added. "The people want to propose this and that, and the government needs to find solutions for them. Thus, it's mostly Cambodian people within the nation."

Hun Sen, who has been in power for more than 30 years, recently announced that Cambodians can send messages directly to his own Facebook page in order to raise concerns and issues.

He also urged officials to create their own Facebook pages along with accounts for government institutions, so that the public's concerns could be collected and addressed.

Political observers believe Hun Sen is hoping that he can harness Facebook to gain popularity in preparation for important commune elections in 2017 and national elections the following year.

This report was produced in collaboration with VOA's Khmer Service.