In the wake of the racially-charged killing of nine African-Americans in Charleston, SC, last month, many have called for the removal of symbols of the Confederacy from public spaces.

Dylann Roof, who was charged with the murders, allegedly posted pictures of himself holding the Confederate battle flag to his website before the shooting spree, along with a racist manifesto.

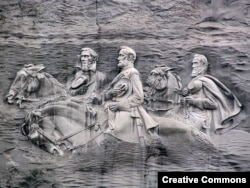

In addition to the Confederate battle flag, some are also calling for the removal statues of Confederate leaders and the renaming of streets and schools named after Confederates.

But that task would be an immense undertaking as the South is replete with homages to the short-lived Confederate States of America.

For example, overlooking Washington, D.C., from the Virginia side of the Potomac River and right in the middle of Arlington National Cemetery sits Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial. Lee, the South’s leading general, owned the plantation there prior to the Civil War.

In the surrounding Virginia suburbs, there are schools named after southern Civil War figures like Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart, two prominent Confederate generals.

Just 90 minutes from Washington, in Richmond, Va., the former capital of the Confederacy, a major thoroughfare called Monument Avenue, is lined with statues and memorials to Confederate soldiers and politicians.

Concerted effort

After most wars, statues and memorials are erected to honor the victors, not the vanquished.

Historians told VOA the memorials are the result of an organized effort by some in the South who set about revising the history of the Civil War, starting nearly immediately after hostilities ended.

“The South reversed the dictum that the winners write the history books,” said Brian Matthew Jordan, an associate professor of history at Sam Houston State University in Texas and author of the book Marching Home about Union veterans in the post-war era.

“They won the battle over the peace.”

Some of the groups are still around today, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

Neither group returned calls seeking comment, but according to the UDC website, the group seeks to “collect and preserve the material necessary for a truthful history of the War Between the States and to protect, preserve, and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor” and to “assist descendants of worthy Confederates in securing a proper education.”

The movement was spurred by several southern groups that wanted to change the narrative about the Civil War. Called the “Lost Cause” movement, it set out to divorce the Confederacy from slavery and make the war about states’ rights and self-government.

In turn, Confederate soldiers were portrayed as heroes for fighting with honor and courage in the face of overwhelming numbers on the battlefield - ideals that all Americans admire and respect.

Much of that was a revisionist interpretation, but Jordan says there was enough of a kernel of truth in the Lost Cause myths to spur its widespread attraction.

And in the North, too, there was a desire to put the war behind the country as quickly as possible.

“The Lost Cause took effect immediately,” said Jordan. “It was a mainstream historical memory for at least the first half century after the war.”

It was during this time that many of the statues and memorials went up.

“In the years after the war, there was a concerted effort made by mostly children of Confederate veterans to try to memorialize the war their fathers had fought, and to valorize and glorify the Confederate cause,” said Carole Emberton, a professor of history at University at Buffalo in New York and author of the book “Beyond Redemption,” which is about the early post-war years in the South.

The Lost Cause movement was driven in part by groups like the SCV and UDC, which collected money to build memorials and commemorated famous battles.

These groups also gave Civil War history a spin that was more palatable to southerners.

“They also did other things like sponsor the writing of school textbooks in the South,” said Emberton. “They tell the story in a way that they approve of. This is where you get stories that slavery was a benign institution and only after slavery did race relations fall apart.”

Even as recently as 2014, Texas, a former Confederate state, was embroiled in a controversy over how school textbooks would address slavery’s role in the Civil War.

In addition to textbooks, the groups also sponsored essay contests and published history papers.

Not just for Southerners

Reconstruction in the immediate post-war years helped galvanize the Lost Cause movement because it was seen by southerners as an attempt by the north to destroy their way of life.

But the Lost Cause wasn’t just for southerners.

A desire to reconcile allowed some of the Lost Cause myths to find support in the north.

For example, "Bby and large, Americans couldn’t agree on exactly how treasonous secession was,” said Emberton.

Also, Jefferson Davis was never charged with treason and was released from prison after two years. Among those paying his bail were prominent northerners, including radical abolitionist Horace Greeley.

In 1870, just five years after the war, the funeral of Robert E. Lee was attended by prominent politicians from the north and, according to Emberton, was “talked about like an American hero.”

The rehabilitation of the South was also embraced nationally because the Civil War was seen as the time when the U.S.--north and south-- lost its innocence, said Jordan.

For many in the north and south, the post-war years saw a sharp rise in industrialization and urbanization and their attendant problems, leading to nostalgia for pre-war days, he said.

“Life seemed to be lurching into the future at a breakneck speed, and the Civil War--awar of unprecedented scale that seemingly confirmed the supremacy of central authority--- seemed now to be in retrospect the moment when the nation took its first steps away from its quaint, and highly idealized, antebellum past,” said Jordan.

Interestingly, the highly controversial Confederate battle flag, which has received most of the attention after the Charleston shooting, was not always featured prominently as a part of the Lost Cause movement, experts say.

Instead, it began to be employed as a protest symbol against the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, in what Emberton said was “like giving the middle finger to southern blacks.”

‘Cultural cleansing’

But amidst calls for the removal of Confederate symbols and memorials, there are those who insist honoring those who fought for the Confederacy shouldn’t be seen as offensive or racist.

Ben Jones, a former Georgia Congressman and currently chief of heritage operations for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, called efforts to remove the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina capital a “feeding frenzy of cultural cleansing” in a USA Today editorial.

“To those 70 million of us whose ancestors fought for the South, it is a symbol of family members who fought for what they thought was right in their time, and whose valor became legendary in military history,” Jones wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “This is not nostalgia. It is our legacy. The current attacks on that legacy, 150 years after the event, are to us an insult that mends no fences nor builds any bridges.”

Jim Webb, a former U.S. Senator from Virginia and current Democratic presidential candidate, said on Facebook it was important to think about the issue with a care that respects “the complicated history of the Civil War.” Webb wrote that his ancestors died fighting for both sides of the conflict.

In a later Facebook post, Webb said he was “deeply concerned that the larger politics of the war are being put onto the backs of the soldiers who were called upon to fight it.”