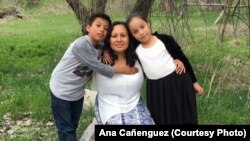

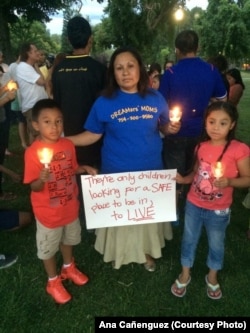

Activist and undocumented immigrant Ana Cañenguez vowed to continue the immigration fight after last week's U.S. Supreme Court deadlock thwarted President Barack Obama's plan to defer the deportation of millions of immigrants like her.

“We will continue [the immigration] fight and urge people to vote in the presidential elections," a tearful Cañenguez told VOA over the phone recently. "It is not over yet."

Immigration advocates are urging Obama to issue a moratorium on deportations after the court let stand a lower court ruling that halted his Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) programs.

The immigration policies would have allowed certain undocumented immigrants and their children to remain in the U.S. without fear of deportation for two years.

Texas and 25 other states sued the Obama administration over the immigration plan, arguing that it was unconstitutional since it conflicted with current federal immigration law.

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, a Republican, praised the court's decision, saying it shows "the president is not permitted to write laws, only Congress is."

“People are really upset and that is driving them to participate and to come out, and what’s happening is people realize without DAPA and DACA, something needs to happen,” said Hairo Cortes, program coordinator at Orange County Immigrant Youth United and one of the partners in the Not1More deportation campaign.

The campaign is hosting a series of Moratorium Now rallies in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and California.

Fighting family separations

DAPA-eligible parents such as Cañenguez are now working in their communities to fight family separation, urging U.S. citizens to vote in the upcoming presidential election, and hoping that Congress will act on immigration reform soon.

A Central-American mother, immigrant and advocate who first came to the U.S. from El Salvador in 2003, Cañenguez said she had to leave her five children behind because of her desire to ultimately give them a better life.

There were days, she said in Spanish, the family did not have anything to eat. “Leaving them was very hard, but I had to do something."

Cañenguez spent eight long years separated from her children. Then her oldest son came on his own after she paid smugglers to bring him to the U.S.

When she heard from relatives that las pandillas, or gangs, were threatening to recruit her next two children, she hired a coyote, or smuggler, to bring them across the U.S.-Mexico border.

U.S. Border Patrol agents caught them walking in the Arizona desert. The 13- and 15-year-old boys were detained for weeks before being released to Cañenguez in Utah. Both boys are under deportation orders.

Not long after, Cañenguez says she began to receive calls from gang members asking for money or they would kill her other two sons still living in El Salvador.

“They think that just because you live in the United States you have money,” she said.

The 43-year-old mother walked miles in the Mexico-Arizona desert and paid another smuggler to help her and the two children cross the border into the U.S.

But the smuggler left the three in the desert. Running out of food and water, the three were apprehended by border patrol agents.

Today, although she is still fighting deportation proceedings, Cañenguez has finally reunited her family in Utah, where she remarried and had two U.S.-born children.

Presidential action

The immigration case, United States v. Texas, which was brought by 26 states, challenged Obama's executive orders and argued that he did not have the power to effectively change immigration laws.

A lower court struck down Obama's action as unlawful and issued an injunction on its implementation – a ruling that stands without precedent after the Supreme Court deadlocked on the case.

Paromita Shah, associate director at the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild, explains, “This was a tie by the Supreme Court so there’s no precedent that has been set. There’s no precedent resulting from this decision, meaning that we don’t have any Supreme Court law on the merit of this program.”

As a result, Shah said there are still ways Obama could help undocumented families in need.

“One of the most important things, and this has been said by some immigrant rights groups across the country, is that the president still can enact a moratorium on people deportation,” she said.

“He still has the authority to do that. He can stop the raids. … Even though there’s a big question of what’s going to happen in this program now, there’s a number of immigrants’ rights groups including us that believe that the president can do things,” she added.

Living in fear

A halt to the deportation raids would protect Lydia Nakiberu’s family.

Nakiberu has called the U.S. home for the past 11 years. She came here after the political and economic situation in Uganda left her without hopes for the future.

Nakiberu lives with her husband, Jerry, and their three U.S.-born children in Massachusetts.

The family experienced tough times when Jerry spent three months in an immigration detention, forcing him to miss their youngest son's birth. He's been fighting his deportation order ever since.

“It was really tough but because we had a great community – people stepped in – to bring us some groceries. People from church really helped us. That’s how we survived,” Nakiberu said.

Nakiberu says her two oldest children understand the situation “at some level” and have told her they are afraid to one day come home from school to an empty house.

“They leave in fear every time they think [law enforcement] will come and pick us up because they know what’s going on," Nakiberu said. "They have this fear that maybe one day they will lose their parents.”