A U.S. based university professor has said counter-terrorism efforts by both U.S. and Ethiopian governments to marginalize or defeat Islamic groups in Somalia might have had the unintended consequence of further strengthening the groups.

But, Kenneth Menkhaus, professor of political science at Davidson College in North Carolina, said he was encouraged by policy shifts both in Ethiopia and the United States to reduce external factors that he said sometimes inflame radicalism in Somalia.

His comments came as a two-day summit on peace and security opens Wednesday in New York City to explore a variety of conflict situations in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and their possible effect on national security.

A workshop at the summit is expected to consider the possible impact of the global jihadist movement on Somalia and whether the global jihad problem has been created by U.S. counter-terrorism efforts.

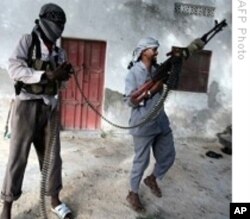

Professor Menkhaus said Somalia is a security threat to its neighbors and the West because of the dramatic rise of the jihadist group al-Shabaab.

“Since 911, and most specifically since around 2004-2005, the rise of the jihadist group al-Shabaab has dramatically increased the security threat that Somalia poses to its neighbors and possibly to Western countries, and the United States. Al-Shabaab has directly affiliated itself with al Qaida, at least rhetorically. It has declared war on both Ethiopia and Kenya. It has a physical presence inside Kenya. That puts it in the position to potentially launch a terrorist attack on that country if it chose to do so,” he said.

Menkhaus said, while over 200 years of international exploitation and colonialism might have contributed greatly to Somalia’s current instability, it is ultimately the responsibility of the current Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to pull Somalia out its quagmire.

“There’s a lot of blame to go around for what has gone wrong in Somalia. Certainly, external actors during the Cold War provided support to a dictatorship that gave rise to these armed liberation movements and devolved into criminal militias fighting one another. Having said that, it is the Somali leaders’ responsibility to pull the nation out of this mess,” Menkhaus said.

He said the international community continues to support Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government despite its weakness because the cost of abandoning the government is high.

“We supported the Transitional Federal Government not because it’s a good option, but because it’s been the best of bad options. There’s real frustration both in Somalia and in the international community about what to do with the TFG. The costs of abandoning it are fairly high. Most observers still don’t want to consign Somalia to yet another round of national reconciliation talks,” Menkhaus said.

Menkhaus reiterated his belief that foreign military intervention has been a significant source of radicalization.

“This has become a vicious circle in which both Ethiopian and U.S. efforts to reduce, or marginalize, or defeat Islamic radicals in Somalia has had the unintended consequence of strengthening them or empowering them in ways that (we) could never have imagined five years ago,” he said.

But, he said he was encouraged by policy shifts both in Ethiopia and the United States to reduce external factors that he said sometimes inflame radicalism in Somalia.