Burma’s political reforms and new ceasefire agreements with ethnic armed groups are raising hopes that the country will also be able to reduce illicit opium cultivation. Ron Corben reports from Bangkok.

This week Burma’s government signed another peace agreement with an armed ethnic army. Leaders reached a deal with the Shan State Army, a militia based in the northern Shan State where much of the country’s opium is produced.

Burma is world’s second largest opium producer after Afghanistan, which is responsible for 90 percent of world opium output.

The U.N.’s Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) says 43,000 hectares were under cultivation in Burma in 2011, doubling the output in five years. Burma, also known as Myanmar, is a major source of amphetamine-type stimulants, most of which are produced in Shan State.

UNODC says grinding poverty and internal conflict in the troubled ethnic regions led to the doubling in production of opium poppy - the raw commodity for heroin.

Armed ethnic groups in the region also had resisted government calls to act as border patrol units.

Now, as Burma’s President Thein Sein presses ahead with political and economic reforms, as well as ceasefire agreements with the militias, the United Nations says the president is also looking to address drug production.

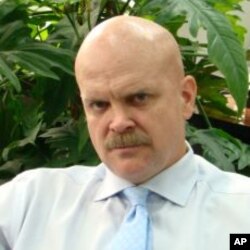

Gary Lewis is the UNODC regional representative for East Asia and the Pacific.

“We see the government developing a three year alternative development strategy; engaged in ceasefire with various insurgent groups and this we believe will give us an opportunity to encourage those in the international community who wish to partner with Myanmar and the communities on the ground to find alternatives to poppy,” said Lewis.

UNODC programs involve farmer support projects in Southern Shan State promoting alternative development.

Foreign aid to Burma has been limited because of allegations of the military’s past human rights record and restricted access for international donors. But analysts say the reforms, including the release of political prisoners, have set the way open for donor funds.

But UNODC’s Lewis says international assistance will be needed for poppy eradication and alternative crop programs.

“We need to do more, like in Shan State in Myanmar, that the international community engages, provides us with the type of financial support that we need at this stage now that the government is welcoming more international engagement," added Lewis. "That will give us access to the areas there where we would then be able to engage with local communities.”

Bertil Lintner, author and analyst on Burma, says only a “political solution” will ensure an end to the economic and social uncertainties that led to drug production.

“I can’t see how any crop eradication program which has to go with the government in an area where the ethnic conflict has not been solved can achieve anything," said Lintner. "You would need a political solution to Burma’s ethnic problems and that is not easy.”

Protection of human rights, especially access to land, also needs to be recognized, says Debbie Stothard, spokeswoman for the Alternative ASEAN Network. Past official eradication programs have often led to land confiscation from local communities.

“There definitely needs to be peace secured in the ethnic areas," she said. "But there also needs to be good governance and there is a danger that international programs used for drug eradication would be manipulated by the government to push local people off their land.”

Stothard says demilitarization needs to occur as the armed forces have been accused of extorting funds from communities She says for effective drug eradication to succeed, legislative and institutional reforms also need to be put in place.