RANGOON —

Burma's political changes are rapidly transforming Rangoon's historic district, where colonial-era buildings are being replaced by modern highrises. But business groups, historians and one of the country's last Jewish families are teaming up to preserve a 100-year-old synagogue in an effort to keep a historic reminder of the multi-religious past of Burma, also known as Myanmar.

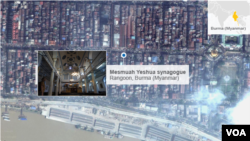

The Mesmuah Yeshua synagogue is in a neighborhood typical of colonial Rangoon. Mosques, Hindu temples, churches, and Buddhist pagodas dot busy streets of markets, hawkers, and hardware shops.

The protected heritage building dates back to 1896, and has been under the care of a member of the Samuels family for generations. Moses Samuels, who has been the trustee of the synagogue for the past 35 years, inherited the role from his father, who inherited the role from his grandfather.

Moses Samuels says he looks forward to when his son will take over his role, and is optimistic for the future of the community.

Sammy Samuels, Moses’s son who recently returned to Burma after studying at a Jewish university in New York, has commemorated all his major life milestones in the synagogue.

“It is the main reason we stick here. We could have closed, we could have moved to other countries," he said. "I used to play around here, I had my bar mitzvah here, I had my Shabbat dinner here, I had, most importantly, my wedding here, and that was the first Chuppah [canopy used in Jewish wedding ceremonies] in 27 years.”

For years, the building fell into disrepair, and even lost its roof during cyclone Nargis in 2008. The U.S. ASEAN Business Council donated funds to keep the synagogue standing, but now the Samuels family is taking it over. Samuels says that as tourism has increased in Burma, the family's travel business, Myanmar Shalom, has benefited, allowing them to afford the cost of repairs.

A dwindling community

In the 1930s there were more than 2,500 Jews in Rangoon, including its mayor, businessman David Sophaer. The vast majority of the community was of Iraqi descent, and began to arrive in Rangoon via India in the mid 19th century as the British empire expanded. Today there are an estimated fewer than 20 local members of the community.

Author and historian Thant Myint-U heads the Yangon Heritage Trust, an organization dedicated to saving Rangoon’s heritage buildings.

He says the synagogue's preservation effort is about more than just the building: it's about recovering Burma's past, to help people understand the city's rich multiethnic history.

“But it’s also about revitalizing old Rangoon and old Yangon and revitalizing this in a way that helps all the people in this city, poor people, working class people, as well as middle class and other people, and help them both appreciate the multiculturalism here, but also help to engender and enable a new cosmopolitan Yangon to emerge in the 21st century,” explains Thant Myint-U.

Integrating religious communities

Moses Samuels agrees that integration of diverse religious communities is important, and says he makes a point of cultivating close personal relationships with other religious leaders in the city.

At a recent ceremony marking Myanmar Shalom's new role as the financial backer of the synagogue, Muslim community leader Aye Lwin pointed out that at a time when some Muslim communities across the country are stricken with sectarian communal violence, religious leaders of all kinds must support one another.

“As a Muslim, Jews are our cousins as we regard them as our member of family, and especially in Myanmar as my brother has just mentioned, there is unity and diversity and we should show our friendship and unity. Religion being abused by politicians that is the main thing. I don’t think there is an all out religious conflict in Myanmar,” said Aye Lwin.

As a gesture of support from Burma's government, the chief peace negotiator for the cease-fires with armed groups in border areas, Aung Min, attended this month's handover ceremony.

“This is part of my intention to celebrate the culture and heritage of the Jewish community in Myanmar. We have longstanding Jewish culture and heritage here but we have less and less which is a sad thing to see so I came here in effort to celebrate that heritage,“ said Aung Min.

As part of the synagogue's preservation plan, authorities are planning to relocate the nearby Jewish cemetery, which houses 700 graves. Since Rangoon's last rabbi left in the 1960s there have been no regular religious services at the synagogue, but it remains open to the public.

The Mesmuah Yeshua synagogue is in a neighborhood typical of colonial Rangoon. Mosques, Hindu temples, churches, and Buddhist pagodas dot busy streets of markets, hawkers, and hardware shops.

The protected heritage building dates back to 1896, and has been under the care of a member of the Samuels family for generations. Moses Samuels, who has been the trustee of the synagogue for the past 35 years, inherited the role from his father, who inherited the role from his grandfather.

Moses Samuels says he looks forward to when his son will take over his role, and is optimistic for the future of the community.

Sammy Samuels, Moses’s son who recently returned to Burma after studying at a Jewish university in New York, has commemorated all his major life milestones in the synagogue.

“It is the main reason we stick here. We could have closed, we could have moved to other countries," he said. "I used to play around here, I had my bar mitzvah here, I had my Shabbat dinner here, I had, most importantly, my wedding here, and that was the first Chuppah [canopy used in Jewish wedding ceremonies] in 27 years.”

For years, the building fell into disrepair, and even lost its roof during cyclone Nargis in 2008. The U.S. ASEAN Business Council donated funds to keep the synagogue standing, but now the Samuels family is taking it over. Samuels says that as tourism has increased in Burma, the family's travel business, Myanmar Shalom, has benefited, allowing them to afford the cost of repairs.

A dwindling community

In the 1930s there were more than 2,500 Jews in Rangoon, including its mayor, businessman David Sophaer. The vast majority of the community was of Iraqi descent, and began to arrive in Rangoon via India in the mid 19th century as the British empire expanded. Today there are an estimated fewer than 20 local members of the community.

Author and historian Thant Myint-U heads the Yangon Heritage Trust, an organization dedicated to saving Rangoon’s heritage buildings.

He says the synagogue's preservation effort is about more than just the building: it's about recovering Burma's past, to help people understand the city's rich multiethnic history.

“But it’s also about revitalizing old Rangoon and old Yangon and revitalizing this in a way that helps all the people in this city, poor people, working class people, as well as middle class and other people, and help them both appreciate the multiculturalism here, but also help to engender and enable a new cosmopolitan Yangon to emerge in the 21st century,” explains Thant Myint-U.

Integrating religious communities

Moses Samuels agrees that integration of diverse religious communities is important, and says he makes a point of cultivating close personal relationships with other religious leaders in the city.

At a recent ceremony marking Myanmar Shalom's new role as the financial backer of the synagogue, Muslim community leader Aye Lwin pointed out that at a time when some Muslim communities across the country are stricken with sectarian communal violence, religious leaders of all kinds must support one another.

“As a Muslim, Jews are our cousins as we regard them as our member of family, and especially in Myanmar as my brother has just mentioned, there is unity and diversity and we should show our friendship and unity. Religion being abused by politicians that is the main thing. I don’t think there is an all out religious conflict in Myanmar,” said Aye Lwin.

As a gesture of support from Burma's government, the chief peace negotiator for the cease-fires with armed groups in border areas, Aung Min, attended this month's handover ceremony.

“This is part of my intention to celebrate the culture and heritage of the Jewish community in Myanmar. We have longstanding Jewish culture and heritage here but we have less and less which is a sad thing to see so I came here in effort to celebrate that heritage,“ said Aung Min.

As part of the synagogue's preservation plan, authorities are planning to relocate the nearby Jewish cemetery, which houses 700 graves. Since Rangoon's last rabbi left in the 1960s there have been no regular religious services at the synagogue, but it remains open to the public.