Burma has some of the strictest censorship laws in the world, but the new government has started drafting a new media law that is anticipated to make major changeson the media environment under reform in Rangoon.

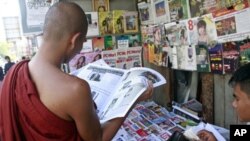

Newspapers bearing the once banned image of democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi are fairly common nowadays in Rangoon. But the 50-year-old censorship laws, a relic of the socialist era, are still in effect.

At a recent workshop on media freedom, Ye Htut from the ministry of information justified the existence of censorship, but also pledged its end by the close of this year.

“We want to maintain the stability and law and order in our country in the previous government before 1962 there’s a press freedom in our country. And instead of informing the general public media themselves created a crisis," he said.

Exile media groups also attended. For some, it was their first visit home in 23 years. Toe Zaw Latt is the bureau chief of the Democratic Voice of Burma.

"Yesterday the information minister was here. He openly said they are willing to change and take reform, which was very encouraging. He said the state's role of media development is to facilitate, not to control, which is quite an amazing statement from a responsible party," he said.

Though editors and journalists already anticipate the end of censorship, the newfound freedom is accompanied by uncertainty in a competitive market for publishers like Ross Dunkley of the English language weekly The Myanmar Times.

"It's going to be a bloodbath. I mean, that's the absolute truth is that you get some [daily newspapers] up and running, then I figure you're going to see in the first year of the dailies at least 100 publications die," he said.

Some topics are still sensitive, such as the formation of labor unions. Last week, a story in the Myanmar Times about the first meeting of what will be Burma's new independent journalist’s union was cut by censors.

The only daily newspapers, such as The New Light of Myanmar, are published by the state. But new liberal laws could mean independent daily news for the first time since 1962.

The union is still drafting its constitution, and it is still unclear what will replace the ministry of information as an independent regulatory body. Associated Press correspondent Aye Aye Win is one of the co-founders of the new union.

“It’s been one year that new government has taken power so I think it’s time that all professional organizations should form their own leagues to help support them protect them and promote their rights," he said.

The end of censorship and increased competition promise big changes for Burma's news industry, and for the country's news consumers.