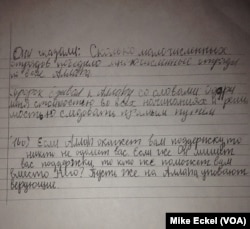

Three short paragraphs - hand-written, in Russian, on lined, notebook paper - sat atop a stack of old newspapers next to the television in the newly vacant third floor apartment at 410 Norfolk Street.

Federal Bureau of Investigation agents had done the first of two searches of the East Cambridge apartment, rented for more than a decade by an ethnic Chechen family, the Tsarnaevs.

Days earlier, on April 15, 2013, two pressure cookers, packed with nails and ball bearings, exploded near the Boston Marathon finish line, killing three, maiming scores and shattering the celebration of the world’s oldest annual marathon.

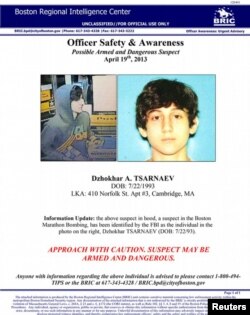

The Tsarnaevs’ two sons had been implicated: Tamerlan, 26, had been killed during a police shoot-out. Dzhokhar, 19, was in police custody.

A friend, who had known the Tsarnaev family for years and was very close to all of them, discovered the paper in the apartment and recognized the handwriting as Tamerlan’s:

"They said: how many small armies had defeated larger armies by the will of Allah. The Prophet called to Allah with the words: give me the perseverance in all my undertakings and the resoluteness to follow the correct path. If Allah will give you support, then no one will defeat you. If he removes this support, then who will help you in place of nothing? Let the devout rely on Allah."

The writing, shared exclusively with VOA, is a glimpse into the mind of the man considered to be the mastermind of the Boston terrorist attack.

Nearly 21 months later, the scars of the bombing - psychological and physical - are deep and raw in the Boston area as survivors, witnesses, Americans and Chechens, from Boston and Grozny, have groped to understand the motivations of the Tsarnaev brothers.

VOA has retraced some of the key steps leading up to the bombing, interviewing members of the Chechen émigré community and others who had close dealings with the Tsarnaev family.

The story that emerges is one of a troubled family buffeted by the challenges of adapting to American culture and by the undercurrents of war and radicalism wracking their ethnic homeland.

The best hope, however, for understanding what led to April 15, 2013, lies with Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, whose trial on 30 terrorism and related charges opens Monday in Boston’s federal court just a few miles from the marathon’s finish line.

“They took the innocence from us, that they did take,” said Jason Rosenberg, a Boston-area lawyer who represents a man once cared for by the Tsarnaev family. “You think you’re immune from [terrorism], it only happens elsewhere.”

“We think: ‘they can’t be these beasts, but we all know that a human being … can be caring and loving to someone else and then be a horrendous person,” he said. “You can be, and are, one and the same, the same person.”

‘Why did you do it, Tamerlan, why?’

A caring and loving person is what Tamerlan seemed like less than four weeks before the bombs sent panic through runners and spectators lining the few hundred yards along Boston’s Boylston Street leading up to the finish line.

Around March 20, Tamerlan, along with his American wife, Katherine, traveled to the outskirts of Manchester, New Hampshire, to visit another Chechen family who had fled the region in the early 2000s: Musa Khadzhimuradov, his wife Madina, and their two children.

Among the two dozen or so Chechen families living in Boston and southern New Hampshire, it was common to mark holidays together, to attend one another’s barbecues, to carry on traditions from back in Chechnya. Tamerlan had come, Khadzhimuradov said, to say goodbye to Khadzhimuradov’s mother-in-law, who was returning to Chechnya.

Khadzhimuradov, who formerly worked as a bodyguard to Chechen separatist leader Akhmed Zakayev, said he had been in touch with Tamerlan since 2006, when they met at a Chechen holiday celebration in Boston.

During the March visit, both Khadzhimuradov and his wife Madina recalled, Tamerlan played happily with his young daughter Zahara, and chatted with the Khadzhimuradovs’ own daughter.

“We didn’t talk about war or religion, nothing,” Musa Khadzhimuradov told VOA. “He was happy. Maybe he had a double life or something, but he was playing with his child.”

“The way [Katherine] looked at him, she couldn't take her eyes of him,” Madina said. “Tamerlan was chatting, playing with his daughter.”

“I see him almost every night in my dreams,” she said. “He looks just as always: very handsome and calm. I cry and I ask him: ‘Why did you do it, Tamerlan, why?’ And he answers: ‘I didn't want to do it here.’”

But according to FBI affidavits, the grand jury indictment and other details made public in media reports, Tamerlan was plotting something destructive.

On at least two occasions in the months prior to April 15, Tamerlan had visited a Manchester firing range just a few miles from the Khadzhimuradov apartment to practice shooting. On March 20, Dzhokhar, who was a student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, joined Tamerlan at the range.

Carey McLoud, an owner and manager of the Manchester Firing Range Line, refused to answer VOA’s questions about the Tsarnaev brothers.

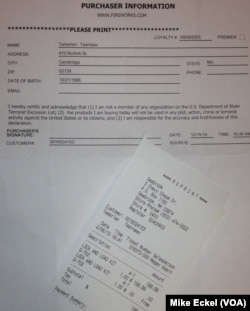

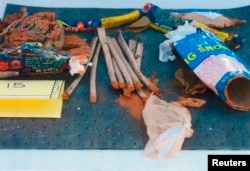

Tamerlan had also traveled to the New Hampshire coastal town of Seabrook to buy fireworks, and gather gunpowder to fuel the pressure cooker bombs. On February 6, at around 7:40 p.m., Tamerlan stopped at Phantom Fireworks and paid $199 cash for a package called “Lock and Load,” and took advantage of a “buy-one-get-one-free deal.” He left with 48 mortars and the equivalent of eight pounds of low explosive powder, according to prosecutors.

“He asked ‘what was the loudest, most powerful firework we had?” store manager April Walton told VOA. “It’s what 80 percent of our customers ask for.”

Sometime around April 5, just 10 days before the bombings, Tamerlan went online and ordered electronic components that could be used in making bombs, according to the grand jury indictment. Those components were delivered by mail to the Norfolk Street apartment.

In recent years, some members of the Tsarnaev family, including the boys’ mother Zubeidat, had begun openly expressing their Muslim faith. They dressed in traditional conservative clothing and attended prayer services, mainly at the Islamic Society of Boston’s Cambridge mosque four blocks from 410 Norfolk Street.

Once a fashionable and flashy dresser, Zubeidat had taken to wearing headscarves, long skirts and long-sleeved dresses and shirts. She reportedly started wearing gloves constantly so as to avoid touching the hands of unrelated males, such as shop clerks or tollbooth workers. The Tsarnaev boys’ sisters, Bella and Ailina, also began wearing headscarves.

Outburst at the mosque

Prior to November 2012, the Tsarnaevs didn’t stand out among the hundreds who attended prayers regularly, said the Cambridge mosque’s acting imam, Ismail Fenni.

That month, a guest speaker gave a sermon about the importance of Muslims accepting public holidays like Thanksgiving. Tamerlan stood up and angrily interrupted the speaker, calling him wrong.

Fenni said he and other elders spoke to Tamerlan and reminded him of the mosque rules of behavior and decorum. Tamerlan nodded and said he understood, Fenni recalled.

Then in January 2013, at the prayer service before the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, Tamerlan again stood up and interrupted the sermon, as the guest speaker discussed how Muslims should accept the civil rights leader.

“There was nothing really for us to be worried about with him before his explosive outbursts,” Fenni said. “Before then, he was just a face in the crowd.”

That first outburst had occurred four months after Tamerlan returned from a trip to Russia’s North Caucasus, where Chechnya is located.

Between January and July 2012, Tamerlan spent some of his time in Makhachkala, the capital of the Dagestan region, working with his father Anzor, who had arrived in the region in April. Anzor was newly divorced from Zubeidat, according to the family friend, who asked not to be identified publicly while discussing the Tsarnaev’s family dynamics.

The stated reason for Tamerlan’s trip in January 2012, according to the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, was obtain a Russian passport: Tamerlan held a Kyrgyz passport, the result of his early childhood in Kyrgyzstan, where many Chechens lived after being expelled from their homeland by Stalin in the 1940s.

But last year, Irina Gordienko, an investigative reporter for Novaya Gazeta, reported that Tamerlan didn’t actually apply for a passport until the end of June, more than six months after arriving.

Gordienko also reported Tamerlan had been in contact with two militants wanted by Russian security agencies. One, a Russian-Canadian named William Plotnikov, was killed by police on July 14, 2012. Within two days, Tamerlan left the region to fly back to the United States.

“People in Dagestan told me he dressed strangely, his behavior was unusual,” Gordienko said. “He wasn’t very knowledgeable about Islam.”

In the United States, Tamerlan had been a show-off from a young age, always seeking attention, the family friend told VOA. He loved to sing, to play violin and to dance. He was smart academically, but he never seemed focused, the friend said: he talked about being an accountant, but he took only a handful of classes at Bunker Hill Community College.

Tamerlan was athletic, as well: he trained at a boxing club in Somerville, next door to Cambridge. His boxing career, nurtured by his father Anzor, hit a high point in February 2010 with a regional trophy. Then it petered out.

“He didn’t seem to know where he was going,” the friend said.

Over the years, Tamerlan pulled income from short-term jobs.

In 2009, he worked as a driver for a Watertown-based elder care facility that catered to Russian immigrants. He also helped his mother with her work as a home health aide in the Newton home of Donald and Rosemary Larking.

Donald Larking was an older man who became so close to Tamerlan that he attended prayer services at the Cambridge mosque, according to Rosenberg, Larking’s lawyer. Larking also had constant discussions with Tamerlan about politics and espoused dark conspiracy theories about the attacks of September 11, 2001.

Through Rosenberg, Donald Larking refused to be interviewed for this article.

Tamerlan was interviewed by the FBI in 2011, at the request of the lead Russian security agency, the FSB, which had been monitoring Tamerlan’s alleged interactions with radical groups. Chechnya had by then suffered through the second of two wars since 1994, and the turmoil had spawned a terrorist insurgency, influenced by Islamic extremists, that had affected the entire North Caucasus.

According to an FBI statement, the Russians reported that Tamerlan “was a follower of radical Islam” and “had changed drastically since 2010 as he prepared to leave the United States for travel to the country’s region to join unspecified underground groups.”

The youngest Tsarnaev

Dzhokhar, by contrast, was considered smart but quiet, always in his older siblings’ shadow, according to friends and acquaintances.

When the family moved to the Boston area, Dzhokhar, then 8, spent second grade at an elementary school in Needham, a Boston suburb. He lived with the family of a prominent Chechen doctor, Khassan Baiev.

Baiev’s daughter Maryam remembers Dzhokhar, who later called himself Jahar, as a happy boy who was good at math, who liked to rollerblade and bicycle around the neighborhood playground.

As they grew older, however, she said she had few interactions with him, only occasionally by Facebook.

“I remember when I saw him on TV… I ran straight to my brother, and said, “Did you see who was on TV?’ He said “Yeah, I saw it,’” Baieva, 21, said. “I was more upset. I felt bad for [Dzhokhar] and I felt bad for his parents, everything he put them through.

“I felt heartbroken, betrayed at the time. It was scary, because I didn’t know how people were going to look at me after, what people were going to think of me afterward,” she said.

Unlike with Tamerlan - the trip to Russia, the mosque outburst, the initial FBI investigation - Dzhokhar’s involvement in the attack was even more baffling. According to friends and acquaintances, he never elicited attention or worry prior to April 15, 2013: not from neighbors or friends, not from school, not from law enforcement.

At Cambridge’s Rindge and Latin high school, Dzhokhar was known as low-key, laid-back and friendly. He was captain of the public school’s wrestling team, an honor student and the recipient of a small scholarship from the city of Cambridge.

At the Dartmouth campus of the University of Massachusetts, Dzhokhar was known as a middling student and, according to The Boston Globe, an active dealer of marijuana.

“Dzhokhar kept to himself, he was smart. He made his own choices,” the family friend said. “He wasn’t the center of attention; he was always off to the side.”

“I never worried about Dzhokhar,” the friend said.

In the months immediately before the bombing, the Norfolk Street apartment was occupied only by Tamerlan, his wife and their daughter. Katherine worked as a home health aide. His parents were both living in Russia. His sisters had moved out.

On the Dartmouth campus, according to prosecutors, there were indications that Dzhokhar was exploring violent acts. Sometime in the spring of 2013, Dzhokhar downloaded to his computer several books and pamphlets espousing radical Islamist ideas.

One was a book that contained a passage by a well-known al-Qaida propagandist, Anwar al-Awlaki. Another was a copy of the summer 2010 issue of Inspire magazine, an English-language publication by al-Qaida’s affiliate on the Arabian Peninsula.

The issue contained detailed instructions about making a pressure cooker bomb using common materials in an article titled: “How to Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom.”

After his arrest, investigators later found Dzhokhar’s college dormitory room, his computer and a backpack containing fireworks that had been emptied of gunpowder.

The night of April 15, Dzhokhar sent a friend— the son of a prominent Boston-area Chechen émigré— a text message asking him if he was at the marathon and was OK.

On April 18, as police widened their search for the alleged bombers, the brothers shot and killed a police officer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, according to the grand jury indictment. Hours later, as the manhunt began closing in, Dzhokhar sent another text message to a college classmate saying: “If you want u can go to my room and take what you want.”

In the early hours of April 19, with Tamerlan dead and the suburban town of Watertown resembling a war zone, Dzhokhar, bleeding from multiple gunshot wounds, huddled in a boat parked in a backyard driveway.

Inside the hull and on an overhead beam, he scrawled several messages that give some insight into his motivations, according to the indictment:

“The U.S. Government is killing our innocent civilians; I can't stand to see such evil go unpunished; We Muslims are one body, you hurt one you hurt us all; Now I don't like killing innocent people it is forbidden in Islam.... stop killing our innocent people and we will stop.”Trial as closure

For victims, for friends of the Tsarnaev family, for Chechen immigrants, for marathon runners, for arguably just about everyone in Massachusetts, the trial scheduled for Monday is likely to be a riveting spectacle.

For some, it will be a chance at vengeance and punishment for a young man whose seeming potential crashed to a halt on April 15, 2013.

For others, it will be a chance at learning something more about why a laid-back, average, 19-year-old college student decided to participate in a horrific attack on bystanders celebrating a beloved sporting event.

“I want to know why he did it. I want to know why he would go out of his way, what did he need when he already has everything,” said Baieva, the childhood friend.

On December 18, Dzhokhar appeared at the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse, on Boston’s waterfront, his last appearance before the formal beginning of his trial. It was his first public appearance since July 2013, when, still visibly wounded from the manhunt, he told the court he entered a plea of not guilty.

During the 30-minute appearance on December 18, Dzhokhar – sporting a shock of bushy hair and a thin beard – played nervously with his hands and smiled occasionally when talking with his lawyers.He stood when the judge addressed him directly, and he responded respectfully, saying “yes, sir,” and “no, sir.”

Federal prosecutors have indicated they will seek the death penalty if Dzhokhar is convicted. His defense lawyers are expected to seek leniency from the jury, arguing that Dzhokhar was an accomplice, but decidedly under the sway of his older brother.

Defense lawyers have also made a flurry of last-minute court filings, seeking to either delay the trial or move it out of state. A filing last Monday by Tsarnaev’s lead lawyer, Judy Clarke, suggested that the defense was trying reach a deal with the prosecution: possibly a guilty plea in exchange for a life prison sentence.

“If the government remains unwilling to relent in seeking death, and the case therefore must be tried, the defense is asking for nothing more than a trial that is fair,” she wrote.

The trial portends renewed grief not only for the victims of the bombing. For the refugees of the Chechen wars and oppression, who came to the New England over the past two decades, settling in the United States was a chance for them to rebuild a semblance of peace and prosperity. The Boston Marathon bombings shattered that dream.

Upon reaching the United States, “for the first time in my life I felt that I, my kids, my family – that we are safe and happy here. I prayed for America every evening,” said Madina Khadzhimuradova, the Tsarnaev family friend.

“Now it is all gone. I am living in fear again, just like in the old times in Chechnya. We spoke about moving somewhere else, but where can we go? There is no place for Chechens on this Earth.”