Rwandan dissidents have died under mysterious circumstances inside and outside the country with alarming frequency in recent years.

On September 14, Revocat Karemangingo, an ex-Army officer, was gunned down while driving in Mozambique. Since 2016, Karemangingo had told authorities he had been targeted for assassination.

Earlier in September, a popular Rwandan rapper known as Jay Polly died while in custody after Rwandan authorities said he consumed a lethal concoction of methanol, sugar and water.

In February, opposition politician Seif Bamporiki was pulled from his vehicle and shot to death in South Africa in what police said was a robbery, but many Rwandan exiles say was a targeted killing.

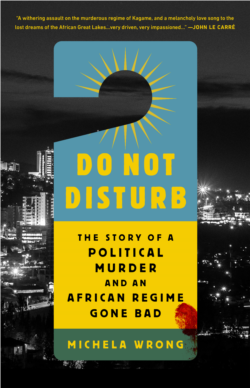

In her new book, “Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad,” journalist Michela Wrong examines the ways in which dissent is silenced inside and outside of Rwanda. She also looks at the roots of the quest for power and asks why evidence of ruthlessly silencing opposition has not tarnished the reputation of the country.

“Despite the evidence of intimidation and harassment, people being beaten up, followed, threatened, the image of Rwanda abroad remains extraordinarily whiter than white,” she told VOA. “And it doesn’t seem to matter how much of this information comes out, both Western politicians and all these philanthropic foundations that engage with Rwanda, the Gates Foundation, Bill Clinton’s foundation, the Blair Foundation, Paul Farmer, Howard Buffett, it doesn’t seem to impact their relationship with Rwanda.”

The title of Wrong’s book “Do Not Disturb” refers to the universally recognized sign travelers hang on hotel room doors. In this case, she said the sign was a grizzly clue left by assassins in 2014 after they strangled Patrick Karegeya, a former Rwandan intelligence chief who was living in South Africa. Karegeya had become a critic of Kagame and was stripped of his rank and imprisoned before fleeing to South Africa to live in exile.

Wrong, who knew Karegeya, paints a picture of a gregarious political dissident who trusted people he should have feared.

“He trusted people, which is a very strange thing to say because you’d think if you were the head spy really for a long time in Rwanda, you would be very careful, very cautious, but when he decided he liked somebody he just trusted them,” Wrong said. “And in fact, that’s the characteristic that got him killed because he was lured to his death by somebody he thought was a friend.”

Wrong details how a Rwandan businessman, Apollo Kiririsi Gafaranga, befriended Karegeya and asked that he book a room for him at the upscale Michelangelo Hotel in Johannesburg. On New Year’s Eve, according to South African authorities, Gafaranga lured Karegeya to the hotel room for drinks, but instead he was killed by Rwandan assassins who had booked a room across the hall.

South Africa has issued arrest warrants for two Rwandans including Gafaranga, but the suspects fled South Africa immediately after killing Karegeya and Rwanda has refused to hand them over, authorities said.

Wrong said this political killing is an entry point to understand the regime of Rwandan President Paul Kagame.

Kagame was a schoolmate of Karegeya in Uganda, and they served together in the bush war led by Yoweri Museveni to overthrow President Milton Obote and later became president himself.

Upon taking the helm of Rwanda in 2000, following several years as a powerful vice president, Kagame was praised by many in the West as the savior of the country and was a darling of donors. However, Wrong outlines a pattern of quashing dissent and the disappearances of political dissidents that show a different side of the longtime president.

She interviews numerous people who served alongside Kagame in Uganda and later in the Rwandan Patriotic Front and found that he earned the nickname “Pilato” for the way he would turn in fellow soldiers who had broken rules, often resulting in their being executed.

“Kagame is not somebody who wants to be liked,” Wrong said. “And I think it’s very obvious that he has a different style of rule from [Yoweri Museveni’s]. Even if you’re not somebody who is deeply critical of his career you can see that he wants to be feared. He wants to be respected. He does not want to be popular. He’s constantly telling people in interviews that he really doesn’t care what the world thinks of him and he doesn’t really care what his voters think of him. He just wants their respect and their obedience.”

Kagame responds

In a television interview, Kagame denounced the book saying it was a biased product of Wrong’s personal connection with Karegeya and was sponsored by enemies of the country.

“By the time it came out, we had known it was being written for about a year or two, and we know those who sponsored her to do it both from outside and those in the neighboring countries, some from far away north others from here,” he said. “And again, it was part of that ‘Rwanda should not be allowed to be what it wants to be, the people of Rwanda should be cut to their size.’ And so, one way of doing it, attack those you want to attack. Attack the leaders or even individuals.”

But the book has come at a moment of heightened scrutiny of Kagame’s government. In September, Paul Rusesabagina, who was depicted as a hero in the film Hotel Rwanda, was convicted on charges of supporting a terrorist group and sentenced to 25 years in prison. The conviction drew condemnation from human rights groups who believe he was effectively kidnapped and brought to the country and did not receive a fair trial.

It also drew a rebuke from U.S. State Department spokesman Ned Price who said the U.S. was “concerned” by the objections from Rusesabagina that he did not have “confidential, unimpeded access to his lawyers and relevant case documents and his initial lack of access to counsel.”

Wrong says she believes the arrest was a way of sending a message to dissidents all over the world that they are not beyond the reach of Kagame.

“I think that was definitely an element of: ‘I’m going to show anyone who is thinking of standing up to me, I can get anyone wherever they are.’ And now that’s a very powerful message,” she said.

But it remains to be seen what price Kagame will pay for the crackdown on dissidents. The Rusesabagina arrest has garnered global attention in a way that other arrests and alleged assassinations have not.

“Was it worth it, because behind Rusesabagina, you know you’ve got all the people that hadn’t been looking at Rwanda, hadn’t been examining what Kagame is doing and how the regime has changed are suddenly interested,” Wrong said. “So, you think, the reputational risk that Kagame is running as a result of this trial, was it really worth it? Because small things can damage reputations in totally disproportionate ways.”