Epitou nan lang Kreyòl Ayisyen

NEW YORK — On a hot and humid August day, Vania Andre walks to a shared workspace in Brooklyn for her first meeting of the day.

A second-generation Haitian American, Andre is the first female publisher of The Haitian Times: a position that carries a lot of prestige and responsibility.

Arriving in a conference room to meet with her team, Andre is poised for work — iPad and electronic pen in hand as she works out a technical issue with a Zoom call.

With the equipment back online, Andre starts the meeting. First to speak is Cherrell Angervil, the paper's social media engagement director.

The conversation among colleagues is easy and friendly as they go over areas of coverage, engagement and experiences. When it is Andre's turn to speak, she focuses on stories, community, numbers, strategies and clicks.

"Overall, from the past week we have seen a dip in traffic," Andre says, adding that July and August are often slow months.

"The previous week all the news cycle focused on the possibility of Kenyan troops coming into Haiti," she continues, adding that those stories bring an increase in traffic and engagement on social media.

Born and raised in Queens, Andre has worked up through the newsroom to become publisher and editor-in-chief of The Haitian Times.

Founded in 1999 by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Garry Pierre-Pierre, the New York-based English-language paper serves and reports on the Haitian diaspora.

And with New York home to one of the largest concentrations of Haitians in the United States, the paper has a ready audience.

"We have a huge diaspora because of all the political and social upheaval that had happened over the course of several decades. We have a lot of our community that are going all over the world," Andre tells VOA as she talks about Pierre-Pierre's decision to leave the New York Times and create his own media outlet.

"But despite that, our culture and our love for our community is so important," she adds.

"We still need to have information about what's going on at home, and in the communities where we're now creating this second home."

Coming from a Haitian family in New York, Andre was already aware of the importance the paper played in the community.

Originally a weekly, The Haitian Times has evolved into a multimedia outlet focused on stories in English about events happening in New York, Florida and Haiti in relation to the diaspora.

The paper is cemented in the community now. But in its early years it had some pushback. Some questioned why it was published in English and not Creole or French, Haiti's main languages.

Andre says that publishing in English helped the paper reach a new generation of Haitians growing up in New York, and people outside the diaspora who also need to know what happens in the community.

Andre started at The Haitian Times in 2014, focusing on its editorial content and the business side of the publication.

But she didn't set out to work in journalism. The change came as Andre became "exposed to the full breadth of Haitian culture through work." In doing so, she says, "it just made me fall in love more with my community."

The paper's founder, Pierre-Pierre, gave part ownership of the paper to Andre in 2018, and the pair work closely together.

After speaking with VOA, Andre joined him and Angervil across the street. Walking to a restaurant for a working lunch, the group discusses updates on new stores and restaurants in Little Haiti.

Over lunch, Pierre-Pierre talks of the challenges his team faced as they built the publication.

"I remember one former city councilwoman, very nice. She said that Haitians were really, really isolated," Pierre-Pierre told VOA. "We weren't," he said. "We just didn't speak English."

As a relatively new community arriving in New York, Haitians tend to keep to themselves, but "our mindset was never to be so insular," he says.

Still, more than 20 years on from those early days of the paper's founding, the Haitian diaspora and The Haitian Times have made their voices heard.

The community now has four members who hold chair positions at the New York City Council as of January of this year, and the Newkirk Avenue subway station in the heart of the community in 2021 was renamed Little Haiti.

A lot of that progress is due in no small part to the paper's coverage, team members say, even if it did take a while for the community to support their approach, which looks at the good and the bad in the community.

"A few years ago, we did a series of articles looking at the discretionary spending and the budget [of] various city council members who were either Haitian descent or representing large Haitian communities," says Andre. "And we saw that they were spending their money … let's say on arts and culture funding for the Pakistani community."

The findings surprised the outlet, Andre says, because with the community's ethnic makeup, they expected more Haitian projects to be funded. "We got a lot of flak for those stories, as you can imagine, a lot of angry phone calls."

But the next budget season, Andre says, they saw a change, with elected officials increasing "funding that they were giving to Haitian-based organizations."

The lunchtime discussion cuts short as Andre has another call lined up. This time she's speaking with New York's Columbia University, where she is interviewing to apply for the Sulzberger Executive Leadership Program.

Leadership program interview over, Andre joins VOA on a walk through Little Haiti, stopping to speak to people and asking if they know of The Haitian Times.

One of them, Steven Dorscen, tells VOA he believes the news is very important.

"I think the news helps us know everything that's happening in the Haitian community, wherever they are located — the community here in Brooklyn as well as in the other states," says Dorscen.

Andre says getting out to talk to people in the community is a must. Over the years she has found that interacting with the diaspora not only helps her to know the audience, but also to find out which stories are most important to them, such as migration.

With Haiti experiencing serious unrest, gang violence and economic and socio-political instability, large numbers have left for countries including Chile, Mexico and the U.S.

According to the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, "as of mid-February more than 5,000 Haitians arrived in the U.S. through a new humanitarian parole program that allows people in the United States to sponsor arrivals coming by plane."

Seeing the influx of new arrivals — and a surge in mis- and disinformation spreading fast through the social media groups that diaspora often use to communicate — The Haitian Times looked for strategies to ensure access to verified information.

One idea: a newsletter to help break down immigration policies.

"We really wanted to be able to think of a way that we can consolidate all this information into one place that anyone could pick up, whether they're at the doctor's office or at a community center," Andre says.

That effort and others are part of a wider strategy to reach as many of the diaspora as possible.

But for Andre, leading the paper through this moment is also personal.

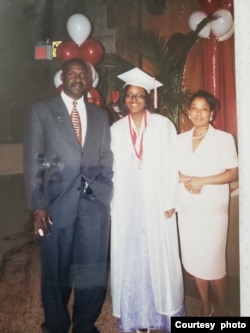

"When I look at that happening nationally, I kind of see that in my own personal story, and my parents coming here. And then me being able to help shepherd our stories for the next, you know, decade to decades to come."

Even before she took the helm, Andre was familiar with the paper's work.

"I remember being a kid growing up in southeast Queens, Cambria Heights, seeing my dad read the paper and then to see, you know, now 15 or 20 years later that I'm the one that's really helping to shepherd our new path forward. It's something that I could have never imagined."

Others in the community have similar stories.

At Bon Bonbon, a restaurant a few blocks from the paper's workspace, owner Jensen Desrosiers greets Andre, Pierre-Pierre and VOA.

Desrosiers has known the paper's founder for years, and says the Times is a necessity, "not only to identify where Haitians are, but what do they think, what are they saying and what their culture is like."

Before the paper, he says, the community felt marginalized. He recalled a mass protest in 1990, when 150,000 Haitians marched in New York over federal restrictions on blood donations.

"We wanted a voice to carry across the English-speaking audience," he says. And when The Haitian Times was later founded, it "became that voice that we were looking for."

As Desrosiers talks about the protest and more recent issues including employment, Andre listens. She later tells VOA that at times she feels like a "computer with too many open tabs" as she works on the various aspects of keeping the paper running.

But even on the busiest days she has one clear focus: to keep The Haitian Times as the go-to diaspora paper and to reach more Haitians.

"My dream is that we have the capacity to cover the diaspora globally," she says. "When we first started back in 1999, the Haitian diaspora was primarily in South Florida and New York. Now, we have communities in the Carolinas, in D.C., Georgia, California, Mexico, Chile, Brazil, France and in parts of Africa."

With the situation in their home country uncertain, the paper helps preserve the Haitian identity while keeping the diaspora informed.