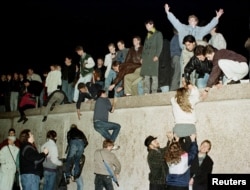

It has been 25 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall signaled the beginning of the end of the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany. As Berliners celebrate this weekend, there's a growing “ostalgie” – nostalgia for the old East Germany.

That enthusiasm has spawned a mini-industry in products and tourism.

A "Trabi Safari" sets off from base camp near the old Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin.

For millions of East Germans, the Trabant was the main mode of transport. The East German-made auto’s design, with a plastic body and two-stroke engine, barely changed from the 1950s to the 1990s. More than 3 million were produced.

"It's very popular because it's a cute car with its round eyes," said Simona Matern, who guides the safari around Berlin sites. "It looks very nice. And lots of West Germans didn't get the chance to drive one. The young East Germans were too young so they couldn't do so."

The Trabi was also a means of escape for thousands of East Germans when the Berlin Wall fell. Families packed in their belongings and fled. The lines of Trabis were cheered as they arrived in West Berlin.

The Trabant is an example of what's become known as “ostalgie” – nostalgia for the iconography of East Germany.

Relics of East Germany

Relics of the period are on display at Berlin’s East German Museum, also known as the DDR Museum. It allows visitors to experience the everyday East German life, ranging from the mundane to the sinister.

"As a museum, we would say we are not 'ostalgic,' because we also remember the political aspects" of East German life, spokeswoman Melanie Alperstaedt said.

The museum has a mock-up of a Stasi or secret police interrogation room and a true-to-scale cell from the notorious Stasi prison in East Berlin.

Fear of forgetting past

Some fear the ostalgie, and its related tourism, is glossing over the horrors of the past.

Berlin's mayor has warned of the dangers of allowing East Germany to achieve cult status.

Alperstaedt echoed those concerns.

"When you have been a nonpolitical person, just living your own life, not thinking that much about the society, then you can say, 'OK, I lived a happy life, I had no problems with the state security, I wasn't imprisoned,' ” she said. "But for the people who were interested in politics, who wanted to have their freedom, who wanted to vote – for them, it was so difficult to live in the German Democratic Republic."

The surviving infrastructure of the old regime provides a strong antidote to ostalgie. One is the so-called Palace of Tears, a checkpoint at Friedrichstrasse Station.

The Berlin Wall divided families and friends overnight. Reunions were rare. Loved ones were separated, sometimes for several years.

A testimonial

The Berlin Wall Memorial is a powerful testimony to the conditions in the East that drove so many to try to escape.

"There was no political freedom of speech, no freedom of travel, no freedom for the press," said its director, Alex Klausmeier. "And the Stasi, the secret police, was everywhere. They were trying to find out everything about the opposition."

For younger generations in unified Germany, ostalgie is confined to museums and history books. For many who grew up in the East, childhood nostalgia is mixed with painful memories.