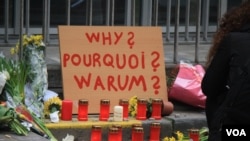

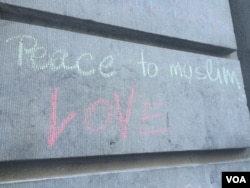

Flowers, candles and chalked messages on the sidewalks adorn both entrances to the Maalbeek metro station. Many passers-by stop and briefly honor the dead. Others stay to weep.

"I don't have any words for this, really," said Bertrand Birson, a 24-year-old car salesman. "I'm just angry … what did we do? What did these people do? Nothing."

The Belgian government continues to search for at least one missing bomber after three blasts Tuesday killed 31 people and injured about 300. Many are still in critical condition.

With no way to truly understand the senseless violence, many Belgians are asking the same question as Birson: Why us?

Islamic State (IS) militants have claimed responsibility for the attacks, and the government continues to discover evidence that the Belgium bombings were linked with the militant rampage in Paris in November that killed 130 people.

The symbolic value of attacking Belgium, often called "the heart of Europe," is not lost on the public in Brussels. Belgium is home to the European Union, NATO and countless other international organizations and is also known as Europe's capital.

"They did not really choose Belgium, they chose the world," Birson explained. "They chose a culture and civilization that's not their civilization. I would say Brussels because Brussels is the heart of Europe."

Marginalized

On the other side of town, Molenbeek district is as poor as it is diverse. At a shop, the clerk, Mohammad, sells Moroccan creams, Islamic clothing and books about Islam in French and Belgian Dutch.

While a disproportionate number of militant extremists have come out of this area, he says that doesn't reflect local sentiment, but the beliefs of a small minority that feels ostracized from this already marginalized community.

"If someone's child goes to Syria to fight, it's considered shameful," he said. "The family will hide it."

Belgium has more young men and women per capita now fighting with IS in Syria or Iraq than any other country in Europe. Some of the Belgium bombers and Paris attackers were from Molenbeek, and people from the area have been involved in past extremist attacks.

However, it is unfair to suggest the area is responsible for the growth of radicalism in Belgium, according to Thomas Devos of JES, an aid organization that helps young people in the area self-motivate to improve their lives and their communities.

On one hand, he says, there is discontent in Molenbeek.

"They don't feel like they are part of society," he said of disaffected youths. "They say, 'There is nothing for us. We have no jobs. We have no decent housing.' "

On the other hand, associating an entire neighborhood with a tiny group of violent extremists is dangerous, as it stigmatizes people simply for where they live. "Mothers are afraid," he said, "They say, ‘Will my kid find work? He is from this area.' "

Fractured society

Belgian authorities have admitted to making mistakes leading up to the bombings, and this week both the interior and justice ministers offered to resign. Among other missteps, Turkish authorities warned the Belgian government that one of the bombers sought to join IS fighters in Syria before he was deported from Turkey.

The fact that authorities make mistakes or find themselves unable to act comes as little surprise to many locals.

Brussels is divided into 19 communes, each with its own local leadership. And they don't always get along. Police forces are also divided and, because the country has two official languages — French and Dutch — as well as many native German speakers, local authorities frequently do not share a common tongue.

"[Authorities] knew they were here for a long time," said Vincent Gilson, a Spanish taxi driver in Brussels, speaking of the bombers. "And they just let them stay."

But Belgium alone is not responsible for increased violence in Europe, says General Michael Hayden, a former director of both the CIA and the National Security Agency in the U.S. The European community, seated in Brussels, has taken on responsibility for currency and trade, but it often fails to effectively share information on security issues.

"The community has taken on things that used to be the province of the sovereigns," Hayden said. "And yet security remains a national responsibility."

And while European leaders met this week to devise new cooperative security agreements, Hayden says the threat of attacks on the continent remains high.

"The great sadness is this is not surprising, and this suggests it is certainly not the last," he said.

At the shop, Mohammad stands up for immigrants and descendants of immigrants in Belgium. The attackers were criminals, he says, unrepresentative of the multicultural nation of about 11 million people — many of whom, like Mohammad, hold a second passport.

"My father was born in Belgium. My grandfather was born in Belgium," he said. "If I am not Belgian, I don't know what I am."