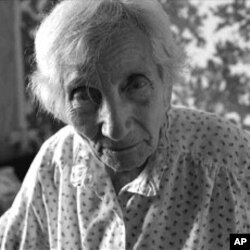

On a recent afternoon, Rosa Faitelson was sitting at her kitchen table eating cucumbers - a typical lunch on just another ordinary day. She didn’t seem at all surprised that strangers walked unannounced into her wooden cottage in northern Belarus bringing her oranges, a rare treat on a hot day. Maybe that composure was to be expected from a woman who, at age 91, had lived through extermination of her people and had decided to stay on when nearly everyone else was gone.

Seventy years ago, on June 22, Nazi forces rampaged through this part of Belarus. In three years, they wiped out 80 percent of the country’s 980,000 Jews. Mobile death units rounded up entire shtetls, or towns, of Jews, confined them to cramped ghettos, and then marched them off to pits where they were shot dead. That’s what happened in Faitelson’s village, Senno.

Some Belarusian Jews survived by hiding in holes in the ground or joining resistance groups in the swampy forests. Others fled east. When the war ended, many Jews couldn’t bear to return to their villages and live near mass graves of loved ones.

In shtetls scattered across modern-day Belarus, only a handful of Jews remain. They are the last guardians of a once thriving culture that gave the world the flying cow paintings of Marc Chagal and the rollicking Broadway musicals of Irving Berlin.

The official Belarus census puts the current Jewish population at close to 13,000, a little over one percent of those who lived here in 1941. Following the war, emigration added to the population decline. Each year scores of young people leave for Israel since poverty and social isolation face them at home.

During the Nazi occupation, Rosa, then an accountant, found safety in Siberia. After the war ended, she resettled in Senno with her late husband. Today she is one of the last five Jews left in what was once a Yiddish-speaking town of artisans.

“There was nowhere else to go,” she says. Her dirt lane no longer lights up on Fridays with Sabbath candles but otherwise the blue-painted homes and water pumps are unchanged from centuries past.

The remaining Jews of her generation are too frail to visit, such as Meltson Shmenko, 90, from down the road who had fallen and twisted his neck when we visited.

But every day, Svetlana Levina, at 57 the “youngster” of the bunch, checks in. When we dropped by, Rosa ordered her to fetch a plastic bucket and collect raspberries in the overgrown garden.

“Eat, eat!” Rosa called out, boiling water for tea. Aside from the little plot in back, she relies on help from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which provides kasha and fuel to survive the harsh winters.

Rosa’s youthful memories are growing hazy. But she recollects shards, such as the ice cream vendors and holidays at the synagogue. The synagogue shuttered after the war when Soviet authorities forbade worship. All that’s left of Jewish communal life are two old cemeteries.

Four hours is a long time to visit an elderly woman, and Rosa seemed exhausted. She looked towards her empty bedroom, which we took as a sign to leave. Rosa bade farewell as matter-of-factly as she had greeted us, and asked us to return soon. There wasn’t anything more to say.