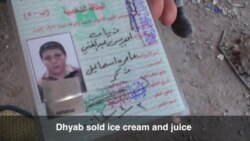

Like most teenagers in Mosul, Iraq, Dhyab Idris Abdulghani dropped out of school once Islamic State (IS) militants took over and changed textbooks into pro-violence treatises.

During their nearly three-year rule of his area, he sold ice cream and juice from a cart on the street.

Then the war for Mosul came to their neighborhood. As Iraqi forces pushed in, the 17-year-old and his family ran. He held a small cousin while IS militants fired at them from behind.

Two weeks later, IS bullets still whiz down the street near where the teenager's body lay slumped against a wall amid personal effects of other civilians shot down. Children’s shoes, photo albums and spare clothes are scattered over bloodstains in the rubble.

It’s 40 degrees Celsius on Thursday and Hazzam Abdulghani can’t tell if the rotting corpse is that of his nephew, but then, he spots prayer beads in a pocket. He holds them in the air and shouts: “Damnation on Daesh!”

Inside IS territory, the Arabic acronym “Daesh” is forbidden, but where Iraq is in control, only the pejorative term for the jihadist group is used.

Continued fire

Hazzam Abdulghani's brothers, two other uncles of the dead 17-year-old, duck their heads and race across the street as IS continues to fire.

“These were his prayer beads,” Abdulghani said. “We need to call an ambulance to take him away.”

“It’s been 13 or 14 days,” the other uncles say, seeming more shocked at the state of their nephew's body than his death. They had tried to search this spot since he went missing, but it was an active war zone closed off by the military until now.

“We are dying in so many ways,” Abdulghani said. “We are dying by airstrikes, mortars and sniper fire. We are dying because we have no food or clean water.”

“I have a friend in the Old City whose two babies starved to death,” adds his brother. The three men nod. This is not an unusual story these days.

Hazzam Abdulghani calls his nephew's father by cellphone to say the body of his eldest son, Dhyab, hadbeen found.

“We will bury him, but don’t bring his mother,” he said. “It’s too much.”

Not found

A few blocks away, a family waits listlessly in a small patch of shade near a makeshift military base. Civilians aren’t allowed further into the battle zone.

Less than a week before, the family had fled IS, even though they were confident Iraqi forces would soon win the neighborhood.

“There was no food and there was gunfire everywhere,” said Waffaa Mohammad, as Sergeant Hussain el-Ghorabi of the Iraqi Federal Police joins the family.

“My cousin’s house was hit by an airstrike,” she tells him. “There are 23 bodies still under the house.”

“Only one small boy of 8 years old survived,” adds another cousin.

Ghorabi explains the procedures for finding lost bodies and gives Mohammad a number to call. “If they aren’t here by noon, call me,” he said.

Mohammad appears dubious. The family had been waiting on the edge of the war zone for four days. “They are all dead,” she said. “We just want their bodies. Nothing else.”

Next phase

It is not clear when the next and potentially final phase of the battle for Mosul will begin.

“This is the Old City,” explains Hazzam Abdulghani, drawing a map on the top of an upside down garage pail as he waits for authorities to pick up his nephew’s body. “Along the outside, there are parking lots. Even civilians can’t drive inside.”

Military trucks and Humvees could never squeeze in, he said.

The areas that Iraqi forces have recently won may be larger than the Old City, he adds, but not nearly as many families were inside.

The United Nations estimates that 100,000 civilians may still be trapped in the Old City, IS’s last and most tightly held stronghold here. More than 230 civilians have been killed by IS sniper fire in recent weeks, and hundreds of others from airstrikes, according to the U.N.

Civilians who have fled IS in Mosul say the death tolls are far higher.

And the coming battle could prove to be the most difficult fight Iraqi and coalition forces have faced to date, adds Ahmed Ghalibi, a soldier with the Emergency Response Division, an Iraqi front-line fighting force.

“They will fight like someone who will die,” he said, leaning on his truck under a bridge, where civilian families gather to be transported out of the war zone after they flee. “They have lots of guns that they haven’t used yet.”

The remaining IS militants in the Old City, he explains, are their best fighters, holed up with their families and bent on killing as many people as possible before they die.

The Old City is all but completely surrounded, Ghalibi added, but front lines are fluid, as IS occasionally advances into areas it once fled.

New, or rarely used tactics may become more commonplace as militants become more desperate, he said. They expect homes, and sometimes refugees, to be wired with bombs, more homemade chemical weapon attacks, and militants forcing families to help them try to escape.

“When ISIS started, they were attackers,” Ghalibi said. “Now they are defenders. They are defending their families, their religion and their lives.”

Photos by VOA's Heather Murdock in Mosul, Iraq