Many years have passed, but traces of the killings are still visible.

Dried blood on the walls, bullet holes, an empty bedroom.

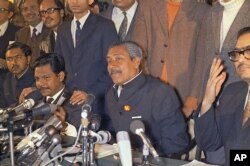

The Dhaka home where Bangladesh independence hero Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and most of his family - including his wife and 10-year-old son - were gunned down by soldiers in 1975, has long drawn visitors since it opened as a memorial museum in the mid-1990s.

Much effort has gone into keeping the location exactly as it was. There’s an old aquarium, a calendar set to the date of the massacre, August 15, and personal items, including a container of Mujib's hair cream.

But changes are in the works. Not so much in the space itself, but in the way the space is accessed. A new curator is planning a virtual version that can be visited by anyone with an internet connection.

“This experience is similar to a pilot during simulations for a plane. If someone wishes to visit the museum, but he resides in a remote area or he cannot afford it, there will be no problem,” said curator Nazrul Islam Khan, appointed to the post last year.

“Any individual can visit the museum anytime she or he wants.”

Khan said the idea is to film 360 degree views later available on the web. The soft launch is in a month’s time. He is also planning an audio guide.

The events of 1975, which transpired almost four years after Bangladesh’s Liberation War against Pakistan, reverberate throughout the country’s contemporary politics.

Mujib, as he is known, is credited with sparking the initial stages of the independence movement. Pakistan threw him in jail during the suppression of the uprising in 1971, but he returned to lead following the war. After the assassination, senior army official Ziaur Rahman rose to power before being shot dead in 1981.

One of Mujib’s surviving daughters, current Prime Minister Hasina Wajed, took over her father’s party, the Awami League, while Ziaur Rahman’s widow, Khaleda Zia, led the main opposition, the Bangladesh National Party. Though Bangladesh is largely Muslim, the Awami League’s secular vision clashed with the BNP’s more religious outlook.

‘Totemic figure’

“Sheikh Mujib is understandably a totemic figure in Bangladesh’s national imagination. However, his importance is swelled for political reasons by the ruling Awami League party and is correspondingly diminished by [the] more right or religious leaning, Bangladesh Nationalist Party [BNP] led governments,” said Joseph Allchin, a journalist and author of the forthcoming book “Many Rivers, One Sea” about the rise of Islamist militancy in Bangladesh.

“Mujib as founder of the party, lends the Awami League stature derived from his leadership in the push for independence from Pakistan. Crucially as well however, his murder, many would contend, helps reinforce the very powerful dynastic status of the current prime minister, his daughter, Sheikh Hasina.”

The fate of the men accused of plotting the 1975 murders tipped one way or the other as power changed hands over the next three and a half decades. Some of the conspirators were initially given diplomatic postings.

Hasina acted after she became prime minister in 1996, but it wasn’t until 2010 that five men were hanged for their roles. A year before, the Awami League had regained control of the government, cementing that control in 2014 with elections boycotted by the opposition.

Critics have accused Hasina of turning Mujib’s memory into a cult of personality. Just this week, 13 teachers were charged with sedition for once comparing an opposition official to Mujib.

Keeping a legacy alive

But while acknowledging that the Awami League may be motivated to preserve Mujib’s legacy in order to secure electoral advantage, the writer Salil Tripathi, who interviewed one of the men who conspired against Mujib, pointed out that the war of independence will be 50 years old in 2021, and a generation will have come of age with dim memories of it or the assassination in 1975.

“The appalling murder of most of her [Hasina's] family is a historical fact she does not want the nation to forget; providing access - even if virtual - to that story is a good sign,” he said, adding that a fuller account of the independence war and the issues underlying it is also essential.

“The struggle between those who would place primacy on religion and those who see the state as secular, with language as the defining characteristic continues. That's the main struggle; keeping Mujibur Rahman's legacy alive is part of that bigger narrative.”

Asked if there was too much uncritical publicity surrounding Mujib’s exploits, Khan, the museum curator, said he was focused on providing more material at the museum.

“Once I took charge of the museum, I prepared a book of speeches of Bangabandhu, which he delivered on different days,” he said, using a name for Mujib that means “friend of the Bengalis.”

“I organized the dates so that the people could find it more thematic and what he had said on what issue and on which date.”