NEW YORK —

Art is thought of as a visual medium, but sound is the focus of a new show at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City.

MoMA presents an auditory landscape with an exhibit called "Soundings, a Contemporary Score."

“The museum-goer walks into a space, and because they are in MoMA, they know they are going to see something traditional, like Picasso," said curator Barbara London. "But they are going to see something very unconventional and maybe surprising. Maybe they’re baffled.”

Many museum-goers are baffled, then amused by Richard Garet’s “Before Me” installation, which amplifies the sound of a glass marble spinning on the metal casing of a phonograph turntable.

Sound, video and memory combine in “Music While We Work,” by Hong-Kai Wang, in which Taiwanese retirees record the sounds they heard during their working life at a sugar refinery.

There’s a common theme among the 16 artists represented here.

“I think most of the artists in the show want you to listen or pause and listen," London said. "They’re saying, ‘Hey, slow down. There are various forms of poetry and beauty in the world.’”

It is the world the unaided human ear cannot hear that animates Norwegian artist Jana Winderen’s sound montage, “Ultrafield.”

Winderen used echolocation devices to capture the ultrasonic radar made by bats, and tiny ultra-sensitive underwater microphones to record the movements of sea beetles less than two millimeters long. She wants to draw attention to endangered ecosystems in the earth’s hidden worlds, and give the listener a chance to experience their magic.

“It's installed in a dark space," Winderen said. "And I am actually hoping people can slow down and enjoy also the listening experience itself, not necessarily thinking about what it is, or what kind of a message I have with it.”

Some sounds are hiding in plain sight, but we don’t have the subtlety of perception to pick them out. At a distance of five meters or so, Tristan Perich’s “Microtonal Wall,” emits “white noise.”

That is a sound containing so many sounds, or pitches, that no individual one can be distinguished. Leaves rustling in the breeze and the ocean surf are both examples of the phenomenon.

Perich has broken four octaves of the musical scale into 1,500 of the pitches that make up those octaves and given each pitch its own small speaker. Close up, or moving slowly past those speakers, one hears their differences.

"My piece, with 1,500 speakers, each playing individual pitches, is still just a finite fraction of this infinite sound," Perich said. "It’s just a gesture towards this idea of the infiniteness of white noise, building it up.”

Sound that is implied, rather than heard, has made some of the loudest buzz at the MoMA show. Camille Norment’s work “Triplight,” consists mostly of a stand-up steel ribbed microphone, circa 1955, used by performers like Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong. Inside the mic, she has placed a bright flickering light.

“One thing I wanted to do was to play with the idea of inability of articulation, the stuttering voice perhaps, this desire to express oneself and the struggle it often entails," Norment said. "And the light casts a shadow that is reminiscent of vertebrae and ribs, or a ribcage or a mask. So the piece, in a way, reenacts the presence of the body that is no longer present.”

Susan Philipsz' “Study for Strings,” is the most heart-wrenching piece in the show. It’s based on a 1943 orchestral work Czech composer Pavel Haas wrote while in a German concentration camp.

Soon after performing the work for a Nazi propaganda film, Haas and his orchestra members were killed. The musicians in Philipsz’ artwork play only two of the parts in the score, emphasizing the absence of the other players.

It’s just one of the pieces in the Museum of Modern Art's “Soundings” show that highlight the dance between silence and sound.

MoMA presents an auditory landscape with an exhibit called "Soundings, a Contemporary Score."

“The museum-goer walks into a space, and because they are in MoMA, they know they are going to see something traditional, like Picasso," said curator Barbara London. "But they are going to see something very unconventional and maybe surprising. Maybe they’re baffled.”

Many museum-goers are baffled, then amused by Richard Garet’s “Before Me” installation, which amplifies the sound of a glass marble spinning on the metal casing of a phonograph turntable.

Sound, video and memory combine in “Music While We Work,” by Hong-Kai Wang, in which Taiwanese retirees record the sounds they heard during their working life at a sugar refinery.

There’s a common theme among the 16 artists represented here.

“I think most of the artists in the show want you to listen or pause and listen," London said. "They’re saying, ‘Hey, slow down. There are various forms of poetry and beauty in the world.’”

It is the world the unaided human ear cannot hear that animates Norwegian artist Jana Winderen’s sound montage, “Ultrafield.”

Winderen used echolocation devices to capture the ultrasonic radar made by bats, and tiny ultra-sensitive underwater microphones to record the movements of sea beetles less than two millimeters long. She wants to draw attention to endangered ecosystems in the earth’s hidden worlds, and give the listener a chance to experience their magic.

“It's installed in a dark space," Winderen said. "And I am actually hoping people can slow down and enjoy also the listening experience itself, not necessarily thinking about what it is, or what kind of a message I have with it.”

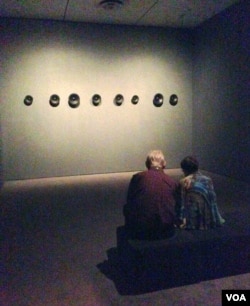

Some sounds are hiding in plain sight, but we don’t have the subtlety of perception to pick them out. At a distance of five meters or so, Tristan Perich’s “Microtonal Wall,” emits “white noise.”

That is a sound containing so many sounds, or pitches, that no individual one can be distinguished. Leaves rustling in the breeze and the ocean surf are both examples of the phenomenon.

Perich has broken four octaves of the musical scale into 1,500 of the pitches that make up those octaves and given each pitch its own small speaker. Close up, or moving slowly past those speakers, one hears their differences.

"My piece, with 1,500 speakers, each playing individual pitches, is still just a finite fraction of this infinite sound," Perich said. "It’s just a gesture towards this idea of the infiniteness of white noise, building it up.”

Sound that is implied, rather than heard, has made some of the loudest buzz at the MoMA show. Camille Norment’s work “Triplight,” consists mostly of a stand-up steel ribbed microphone, circa 1955, used by performers like Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong. Inside the mic, she has placed a bright flickering light.

“One thing I wanted to do was to play with the idea of inability of articulation, the stuttering voice perhaps, this desire to express oneself and the struggle it often entails," Norment said. "And the light casts a shadow that is reminiscent of vertebrae and ribs, or a ribcage or a mask. So the piece, in a way, reenacts the presence of the body that is no longer present.”

Susan Philipsz' “Study for Strings,” is the most heart-wrenching piece in the show. It’s based on a 1943 orchestral work Czech composer Pavel Haas wrote while in a German concentration camp.

Soon after performing the work for a Nazi propaganda film, Haas and his orchestra members were killed. The musicians in Philipsz’ artwork play only two of the parts in the score, emphasizing the absence of the other players.

It’s just one of the pieces in the Museum of Modern Art's “Soundings” show that highlight the dance between silence and sound.