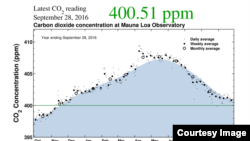

The level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in our atmosphere may never fall below 400 parts per million (ppm) ever again.

That's the headline from a year's worth of test results on CO2 levels from the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii.

In a study released this month, lead author professor Richard Betts of the University of Exeter blames the cyclical Pacific Ocean warming phenomenon known as El Nino in part for the grim record. In his research, published in Nature Climate Change, Betts says El Nino "warms and dries tropical ecosystems, reducing their uptake of carbon, and exacerbating forest fires."

Betts and his colleagues were able to predict this landmark. "I was looking at the numbers this morning," NASA scientist Ben Poulter told VOA. "It is remarkable that they were able to make these predictions in 2015."

Carbon dioxide is odorless and tasteless, and it makes up less than 1 percent of our atmosphere. But this small amount of CO2 has a big impact on the planet. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, without the warming of the planet that carbon dioxide and other so-called greenhouse gases provide, Earth's average temperature would fall below freezing.

But that's where the old saying about too much of a good thing comes into play, because the more carbon dioxide that is in the atmosphere, the more heat will be trapped and the warmer the planet will become.

The planet didn't reach the 400 ppm mark by itself. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels were at 280 ppm. When tests at Mauna Loa began, the level was at 315 ppm. Scientists say human contributions have played a large part in pushing the level over 400 ppm.

All of the carbon people are pumping into the atmosphere is having an impact on the planet. But what exactly is that impact? That's been the challenge facing climate scientists for decades.

At the very least, according to NOAA, warming can cause "sea level rise, shifting precipitation patterns, expansion of areas affected by drought, increasing numbers of severe heat waves, and more intense precipitation events."

Changes underway

Already, some places are getting wetter, and some places are getting drier. The good news is that humans are really adaptable. The bad news is that a host of other creatures aren't.

And it gets worse: A lot of that excess carbon gets absorbed by the world's oceans, making the water more acidic. NOAA says this interferes with such things as "the ability of marine plants and animals to build their shells," and that ultimately threatens "a reorganization of the entire marine food chain, which could lead to a mass extinction event."

But will all this happen? That's the the part that concerns climate scientists the most. Hitting 400 ppm means we're in uncharted territory. The last time atmospheric CO2 levels were this high is unclear, but a number of competing studies put the date at millions of years ago. We may not know whether an extinction event lies ahead, but we can count on weather events like blizzards and droughts becoming more extreme, and more common.

Poulter says the 400 ppm level "tells us that society moving way too fast toward dangerous CO2 concentration in the atmosphere." So what can we do to fix it?

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development says we have to cap the amount of carbon in the atmosphere at 450 ppm. That keeps us below an average global temperature increase of 2 degrees Celsius, which was the goal set at a 2010 U.N. conference on climate change.

But to do that, the world may need to phase out use of dirty fuel like coal and cut back on oil. And according to the White House, "global emissions would have to decline by about 60 percent by 2050 [and] industrialized countries' greenhouse gas emissions would have to decline by about 80 percent by 2050."

Poulter says, "We're only about 15 to 20 years away from reaching the 450 ppm target," which means efforts to cut carbon emissions have to start now. Forty-one nations — including the world's biggest polluters, the United States, China and those in the European Union — have agreed to reduce their carbon output significantly by 2020.

Studies like the one led by Betts can quickly and effectively tell us if the things we are doing to combat climate change are working. "As countries start to implement reduction plans," Poulter says, "we can monitor the effects those reductions are having."