China and a group of 10 Southeast Asian nations face tough negotiations on a code of conduct for avoiding mishaps in the contested South China Sea despite the endorsement of a framework for talks.

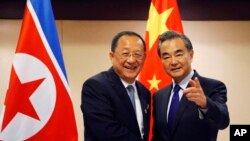

Experts say Beijing will oppose defining the scope of the sea, making the code binding and any enforcement that would limit its maritime activities, whereas the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will ask for those details as discussions go on. The deal has dragged since 2002, with China resisting for much of the past six years. China and ASEAN foreign ministers approved a framework code in Manila Sunday.

“If and when a code of conduct is finalized, we can rest assured that it will be diluted to a point where it does not damage Chinese interests in the South China Sea,” said Jonathan Spangler, director of the South China Sea Think Tank in Taipei.

Beijing claims more than 90 percent of the 3.5 million-square-kilometer South China Sea, overlapping smaller tracts that Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines say fall under their own flags. The code of conduct would be aimed at avoiding accidents as the claimant countries fish, explore for oil and gas or develop some of the estimated 500 tiny islets.

Vietnam and China clashed in 1974, 1988 and 2014 — the first two fights deadly and the latest case over a Chinese oil rig. The code would aim to prevent more such incidents.

But China, as the strongest most aggressive claimant, may fear that a code of conduct would expose or curb some of its maritime activities. Since 2010 it has alarmed the Southeast Asian states by passing coast guard boats through their waters while using landfill to create artificial islets in the Paracel and Spratly chains, some apparently for military installations such as radar systems and combat aircraft.

“We have to see the [code of conduct’s] specific language on land reclamation, although I truly doubt it will have much teeth,” said Yun Sun, East Asia Program senior associate at the Stimson Center think tank in Washington. “For one, China will not support anything against its interests.”

The framework that serves as a basis for talks shuns specifics that might alarm China and instead covers broad advice about avoiding incidents between vessels or aircraft, said Collin Koh, maritime security research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. It might serve too as a topic list for future talks over the coming years.

The framework answers diplomatic pressure from ASEAN on China to negotiate without forcing China’s hand too fast, said Huang Kwei-bo, associate professor of diplomacy with National Cheng Chi University in Taipei.

“This counts as one small step. So China can prolong the negotiating process even longer,” Huang said. “And this way, for China, it’s a deliverable that it can give ASEAN and say ‘see, we’re negotiating with you.’”

ASEAN set out at the start of the year to make the framework a priority under the association’s Philippine leadership through 2017, the Department of Foreign Affairs in Manila said. Just over a year ago the Philippines had won a world court arbitration case against China over its claims in the South China Sea.

Talks on a code of conduct will get tougher, and more drawn out, about a year after the framework signing “euphoria” wears off, Koh said. At that point ASEAN and China will be divided on what to include in the code itself, he said.

ASEAN members will want a legally binding code, possibly ratified by their respective legislatures, with an enforcement scheme and ways of monitoring any incidents, analysts say. Although the code is not supposed to touch on anyone’s sovereignty claim, ASEAN may ask that the code include a clear sea boundary.

China is likely to protest any eventual code clauses on enforcement, legal authority and South China Sea boundaries that cover islands, such as the Paracels, that it controls outright, experts believe.

It will also oppose any link to compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, forecasts Sean King, senior vice president of New York political consultancy Park Strategies.

Beijing cites historical usage records as a basis for its claim to the sea extending from its south coast to Borneo.

In the Philippines, which is hosting the ASEAN meetings, foreign affairs spokesman Robespierre Bolivar urged that talks begin soon and said his country wanted a legally binding code in the end. But he told reporters the code should reflect a consensus.