It all started over yoga.

When an instructor in Kuwait this month advertised a desert wellness yoga retreat, conservatives declared it an assault on Islam. Lawmakers and clerics thundered about the “danger” and depravity of women doing the lotus position and downward dog in public, ultimately persuading authorities to ban the trip.

The yoga ruckus represented just the latest flashpoint in a long-running culture war over women’s behavior in the sheikhdom, where tribes and Islamists wield growing power over a divided society. Increasingly, conservative politicians push back against a burgeoning feminist movement and what they see as an unraveling of Kuwait’s traditional values amid deep governmental dysfunction on major issues.

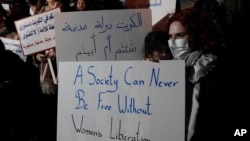

“Our state is backsliding and regressing at a rate that we haven’t seen before,” feminist activist Najeeba Hayat recently told The Associated Press from the grassy sit-in area outside Kuwait’s parliament. Women were pouring into the park along the palm-studded strand, chanting into the chilly night air for freedoms they say authorities have steadily stifled.

For Kuwaitis, it’s an unsettling trend in a country that once prided itself on its progressivism compared to its Gulf Arab neighbors.

In recent years, however, women have made strides across the conservative Arabian Peninsula. In long-insular Saudi Arabia, women have won greater freedoms under de-facto leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Saudi Arabia even hosted its first open-air yoga festival last month, something Kuwaitis noted with irony on social media.

“The hostile movement against women in Kuwait was always insidious and invisible but now it’s risen to the surface,” said Alanoud Alsharekh, a women’s rights activist who founded Abolish 153, a group that aims to eliminate an article of the country’s penal code that sets out lax punishments for the so-called honor killings of women. “It’s spilled into our personal freedoms.”

Just in the past few months, Kuwaiti authorities shut down a popular gym hosting belly dance classes. Clerics demanded police apprehend the organizers of a different women’s retreat called “The Divine Feminine,” citing blasphemy. Kuwait’s top court will soon hear a case arguing the government should ban Netflix amid an uproar over the first Arabic-language film the platform produced.

Hamdan al-Azmi, a conservative Islamist, has led the tirade against yoga, accusing outsiders of trampling on Arab heritage and bemoaning the aerobic exercise as a cultural travesty.

“If defending the daughters of Kuwait is backward, I am honored to be called it,” he said.

The string of religiously motivated decisions has touched off sustained outrage among Kuwaiti women at a time in which not a single one sits in the elected parliament and gruesome cases of so-called honor killings have gripped the public.

In one such case, a Kuwaiti woman named Farah Akbar was dragged from her car last spring and stabbed to death by a man released on bail against whom she had lodged multiple police complaints.

The outcry over Akbar’s killing pushed parliament to draft a law that would, after years of campaigning, eliminate Article 153. The article says that a man who catches his wife committing adultery, or his female relative engaged in any sort of “illicit” sex and kills her faces at most three years in prison. There also can be just a $46 fine.

But when it came time to consider the article’s abolition, Kuwait’s all-male parliamentary committee on women’s issues took an unprecedented step. It turned to the state’s Islamic clerics for a fatwa, or non-binding religious ruling, about the article.

The clerics ruled last month that the law be upheld.

“Most of these members of parliament come from a system in which honor killings are normal,” said Sundus Hussain, another founding member of the Abolish 153 group.

After Kuwait’s 2020 elections, there was a marked increase in the influence of conservative Islamists and tribal members, Hussein added.

Before activists could absorb the blow, authorities called on clerics to answer a new query: Should women be allowed to join the army?

The Defense Ministry had declared they could enlist last fall, fulfilling a long-standing demand.

But clerics disagreed. Women, they decreed last month, may only join in non-combat roles if they wear an Islamic headscarf and get permission from a male guardian.

The decision shocked and appalled Kuwaitis accustomed to government indifference to whether women cover their hair.

“Why would the government consult religious authorities? It’s clearly one way in which the government is trying to appease conservatives and please parliament,” said Dalal al-Fares, a gender studies expert at Kuwait University. “Clamping down on women’s issues is the easiest way to say they’re defending national honor.”

Apart from the defense of what social conservatives consider women’s honor, there is little on which Kuwait’s emir-appointed Cabinet and elected parliament can agree. An anguished stalemate has paralyzed all efforts to fix a record budget deficit and pass badly needed economic reforms.

Nearly two years after parliament passed a domestic violence protection law, there are no government women’s shelters or services for abuse victims. Violence against women has only increased during the pandemic lockdown.

“We need a complete overhaul to address the flaws of our legal system when it comes to the protection of women,” said lawmaker Abdulaziz al-Saqabi, who’s now drafting Kuwait’s first gender-based violence law. “We are dealing with an irresponsible — and unstable — system that makes any reform almost impossible.”

Some advocates attribute the conservative backlash to a sense of panic that society is changing. A year ago, activists launched a groundbreaking #MeToo movement to denounce harassment and violence against women. Hundreds of reports poured into the campaign’s Instagram account with harrowing accusations of assault, creating a profound shift in Kuwaiti discourse.

Organizers in recent months have struggled to sustain the momentum as they themselves have faced rape and death threats.

“The toll it took was massive. We became immediate clickbait. We couldn’t go out in public without being constantly stopped and constantly harassed,” said Hayat, who helped create the movement last year.

Hayat has little faith in the government to change anything for Kuwait’s women. But she said that’s no reason to give up.

“If there’s a protest, I’m going to show up. If there’s someone who needs convincing, I’m going to try,” she said, while women around her pumped their fists and held signs aloft.