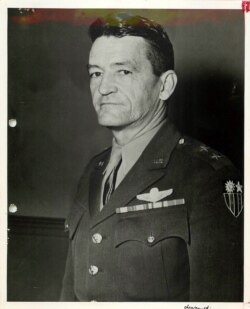

If DNA is destiny, it took an unexpected turn when the grandson of legendary World War II commander General Claire Lee Chennault was growing up.

New York-based jazz musician Paul Sikivie says he was brought up with “a sense of awe” regarding his grandfather, one of the most storied commanders in the Asia theater during that war. But “he belonged to the world at large and not so much to me.”

Sikivie is one of two grandsons of Chennault and his second wife, Anna. His mother is a noted medieval Chinese literature specialist, his father a Belgian-American physicist.

“I wanted to be a geneticist for a while after ‘Jurassic Park’ was made into a movie; I never thought about Chinese language and literature as something for me,” Sikivie, now 37, recalled as he looked back on his childhood aspirations.

By age 14, Sikivie knew he wanted to be a musician. Four years later, he knew his calling was jazz. “St. Thomas by Sonny Rollins came on NPR and I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” he said of jazz’s enduring appeal.

Would that have made sense to his grandfather, who landed on the covers of Life and Time magazines while commanding the Flying Tigers and the U.S. 14th Air Force against the Japanese in China and Burma?

“I don’t know,” Sikivie said. “I’m sure he would identify with the sacrifice and self-determination it takes to persevere in this music, though.”

Sikivie’s parents acknowledge they struggled for years to accept their son’s determination to be a professional musician. That changed when Sikivie told his parents that he had been accepted into the Juilliard School, the world-famous conservatory in New York.

“He sent us an email afterward saying it was more difficult to get into Juilliard than Harvard,” recalled his mother, Cynthia Chennault, noting, "All these years we were after him for his grades.”

Perhaps General Chennault, who despite his reputation for daring and brilliance got into memorable arguments with his superiors, would understand his grandson’s determination to strike out on his own.

“My experience of what I call jazz has been central to my becoming an adult,” Sikivie reflected, “taking responsibility for my choices and actions, being present in the moment. In striving to improve my craft, I had to be disciplined and consistent.”

Even more than an elite musical education, Sikivie values his time on the bandstand with jazz masters. “The knowledge that’s passed directly can’t be gotten any other way, and that’s part of what makes this music special.”

Perhaps his grandfather would also understand the notion of the "band of brothers" that has also been central to Sikivie's journey as a musician. Lawrence Leathers, a noted drummer on the New York jazz scene, was one of them.

Leathers, who died last year, “was like a brother to me. I learned a lot about being present and always reaching for the next level from being around him and playing music with him,” Sikivie said.

Sikivie, Leathers and pianist Aaron Diehl often played as a band, traveling both in the United States and other parts of the world — including China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, where General Chennault had once set foot.

Looking toward the future, the jazz bassist said, “I am continuing to learn how to organize my thoughts, feelings, values into music; there’s really no limit to the ways [in which] this can be accomplished.”