An international crew of six has been in isolation since June of last year as part of a real-time simulation of a manned mission to Mars.

Conducted by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Russian Institute for Biomedical Problems, the Mars500 mission, which ends on ends on Friday November 4, is "the first realistic full-duration simulation" of its kind.

Crew members have been confined to a simulated spacecraft and mock Martian terrain for more than 17 months. Since June of 2010, "home" has been four hermetically sealed, interconnected habitat modules in Moscow that total 550 cubic meters. A separate module simulates Mars.

While the crew did not experience the weightlessness of a space mission, they underwent the psychological and physiological effects of living in an enclosed space for a long time.

After 520 days in isolation, members released audio messages ahead of their "arrival back on Earth."

French crew member Romain Charles said he is most looking forward to seeing his family.

"I know that they will be around, so it will be the first thing that I want to do," he said. "The other thing that I really want to do when I get out is to walk in the park and enjoy the sun. I would very much like it, even if our quarantine may not allow me to do that. And the other thing is to eat something different and delicious, like a croissant for example. I would really enjoy that."

In diary postings on ESA's website, Charles wrote that the team ran out of some its favorite food items, namely tuna in oil and chocolate bars, early on in the mission. During their 17 months, they amused themselves by posting videos of their recipes, such as the way they used crackers and cheese to make so-called pizzas.

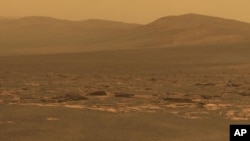

The only variation in surroundings they were able to enjoy: Simulated Mars-walks in the external Martian module, which had lights on the dark walls and ceiling to simulate stars.

Other than that, they experienced few comforts of home.

While crew members could use e-mail to communicate with the outside world, they could speak directly only with one another, and they had to adjust to a 20-minute communications delay when speaking with mission control.

Italian crew member Diego Urbina recalls one personal surprise.

"It was a visit by my mother to the mission control center," he said. "It was the first long conversation that I had in a language different from what we call 'Russ-glish' -- that is, the mix between English and Russian that we speak here. So that was a very nice conversation."

Hailing from France, Russia, China and Italy, the group created a hybrid language to communicate while in isolation. Members will have several days of medical check-ups as they readjust to life "on Earth."

Team Nears End of 520-Day Isolation Test for Mars Mission