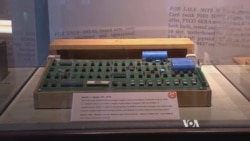

When co-founder Steve Wozniak brought the very first Apple computer to a meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club in 1976, everyone was impressed, but not excited.

"We all thought it was great, a nice job," said Bob Lash, an engineer, inventor and original member of the Silicon Valley hobbyist club. Wozniak's elegant design fit all the computer's workings onto a single circuit board.

"But we were all building our own designs at the time, so it wasn't all that unusual," Lash added. "And nobody at that time had any idea where any of this was going to go."

Apple didn't invent the personal computer. Or the mp3 player. Or the smartphone. That's not how it ended up as the world's largest publicly traded company.

"What is invention?" asked Dag Spicer, curator at the Computer History Museum. "Do you always have to invent something new, or can you take something that exists and rearrange it and make it beautiful? In a sense, I would argue, that is also invention."

It's a form of invention at which Wozniak and co-founder Steve Jobs excelled, Spicer said.

Apple turns 40 on Friday in a world it helped create, where we live surrounded by computers we have welcomed into our homes, offices, cars and pockets.

Beauty and ease of use were Jobs' imperatives, Spicer said; but, that often meant making them hermetically sealed universes of hardware and software that ultimately lost market share to more open ecosystems.

‘This is your friend’

The Macintosh is a prime example. Apple didn't invent point-and-click computing. Xerox did, but was slow to make it commercially available.

Jobs saw the potential. Working with a computer had meant typing lines of text, and often involved special programming languages. Macintosh's graphical user interface brought the mouse to the masses. It was the computer anyone could use, Apple's ads said.

When it came out in 1984, "It was just amazing. Here it was, a sandbox for the mind," said Bruce Damer, who has stuffed practically the entire history of 20th century computing into a barn outside Silicon Valley, called the DigiBarn.

The interface was only part of the package, though. The Macintosh also looked different.

"It's like a toaster," Spicer said. "It's not like a big, scary computer. It doesn't even look like a computer, really. That was a big psychological decision, done on purpose, very consciously, to make it as welcoming and nonthreatening as possible." A smiling little cartoon Macintosh even greets the user on startup.

The Macintosh was designed to change our relationship with computers.

"This is your friend," Damer said.

Take me as I am

The Macintosh was a friend who expected you to accept it as it was.

"The Mac was deliberately designed to be a closed system. Steve Jobs did not want people going in there and pulling out parts or replacing boards or upgrading it. … You can't even get into the case" without a special screwdriver, Spicer said.

"That was the flip side of the easy-to-use equation," he added. "If you limit people's choices, it does make it easier for them."

Then Microsoft Windows brought point-and-click computing to IBM PC-type computers. They were more common and cheaper. More companies made them. And more companies made software for them. Microsoft systems took over and Apple was left with a shrinking market share.

New inventions

Then, Apple invented the iPod and, later, the iPhone.

It's "an ecosystem that's controlled and beautiful," Damer said. "But then you have Android coming out, which is an open source [operating system], and anyone can make an Android handset."

And the same thing is happening. Apple is losing market share.

Apple won't be celebrating its 40th birthday Friday. Co-founder Jobs once said, "If you look backward in this business, you'll be crushed. You have to look forward."

The Los Altos garage where Jobs and Wozniak built the first Apple computers is now an unofficial tourist attraction. In a tribute that's fitting, if not entirely welcomed by the current residents, as a steady stream of visitors goes to take pictures of it on their iPhones.