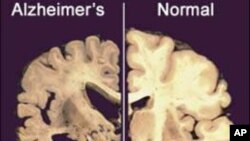

U.S. researchers say a common anti-depressant drug appears to slow the growth of brain plaques that are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Clusters of a protein called amyloid beta are thought to trigger the development of the neurodegenerative disease.

All people produce amyloid beta, or A-beta. But the protein is overproduced and not sufficiently eliminated in those with Alzheimer’s disease. So, rather than being swept away normally, A-beta forms clumps in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease sufferers.

Previous work by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Washington University in Missouri suggested the anti-depressant drug citalopram, which goes by the brand name Celexa, could affect the amount of A-beta that is produced.

Yvette Sheline is a professor of psychiatry at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine. Sheline led two sets of experiments with the anti-depressant. One experiment involved a group of mice genetically bred to have brain plaques.

Two months after the rodents were given citalopram, Sheline says researchers used a microscope to see what was happening to their plaques.

“And what we showed was a dramatic drop in both the number of new plaques that develop and much less growth in the existing plaques," said Sheline.

The drug had no effect on existing mouse plaques.

Researchers also conducted a human trial involving healthy individuals, ages 18 to 50. Writing in the journal Science Translational Medicine, investigators noted a 38 percent reduction in concentrations of amyloid beta in the brain and spinal fluid of those given a single dose of Celexa. Also, the treated volunteers produced less A-beta protein.

“Whether that leads to actually delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease is a whole different question. But we do have a mechanism for decreasing the amyloid concentration," said Sheline.

Sheline said the next step is to enroll healthy, older adults in a study to see whether treating them with the anti-depressant drug for two weeks reduces production of amyloid beta for a longer period of time.

All people produce amyloid beta, or A-beta. But the protein is overproduced and not sufficiently eliminated in those with Alzheimer’s disease. So, rather than being swept away normally, A-beta forms clumps in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease sufferers.

Previous work by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Washington University in Missouri suggested the anti-depressant drug citalopram, which goes by the brand name Celexa, could affect the amount of A-beta that is produced.

Yvette Sheline is a professor of psychiatry at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine. Sheline led two sets of experiments with the anti-depressant. One experiment involved a group of mice genetically bred to have brain plaques.

Two months after the rodents were given citalopram, Sheline says researchers used a microscope to see what was happening to their plaques.

“And what we showed was a dramatic drop in both the number of new plaques that develop and much less growth in the existing plaques," said Sheline.

The drug had no effect on existing mouse plaques.

Researchers also conducted a human trial involving healthy individuals, ages 18 to 50. Writing in the journal Science Translational Medicine, investigators noted a 38 percent reduction in concentrations of amyloid beta in the brain and spinal fluid of those given a single dose of Celexa. Also, the treated volunteers produced less A-beta protein.

“Whether that leads to actually delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease is a whole different question. But we do have a mechanism for decreasing the amyloid concentration," said Sheline.

Sheline said the next step is to enroll healthy, older adults in a study to see whether treating them with the anti-depressant drug for two weeks reduces production of amyloid beta for a longer period of time.