This is Part Three of a seven-part series on African constitutions

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7

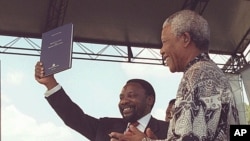

In December, 1996 former South African President Nelson Mandela signed into law the country’s new constitution - a document which experts from around the globe frequently hold up as a model for other countries. But the government has announced a review of the decisions of the constitutional court, which is the custodian of the constitution.

Mandela chose to sign South Africa’s founding law at a ceremony in Sharpeville, south of Johannesburg, where on March 21, 1961, 69 protestors lost their lives to the guns of apartheid. He did so, he said, because the constitution was an embodiment of the principles that aimed to overturn the worst of the country’s past.

South Africa’s constitution was drafted by both houses of parliament sitting as a constitutional assembly between 1994 and 1996. The process involved a countrywide public participation campaign which solicited citizens’ views. While South African constitutional lawyers were the main drafters, they also sought input from global experts.

Modern

Pierre de Vos, who teaches constitutional law at the University of Cape Town, says the document is modern in the way that it regulates the separation of powers of the three branches of government.

But De Vos says the Bill of Rights is also progressive because it not only protects citizens from the excesses of the state, it also, in some cases, requires the government to protect the public interest from other institutions such as large companies.

“And with that goes the inclusion of limited but important social economic rights protections, which places duties on the state in effect to work towards a more fair and egalitarian society,” De Vos explained.

World leader

South Africa’s Constitutional Court has been the arbiter and guardian of the principles in this document for the past 14 years and many legal and ethics experts - including Eusebius McKaiser, associate at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Centre for Ethics - say it has done a very good job.

“Our socio-economics rights cases around housing, around health in particular have been spectacular; we are world leaders when it comes to courts putting pressure on the executive to justify why they are not progressively realizing socio-economic rights in particular instances,” McKaiser said.

The court has in a number of cases ruled against both government departments and President Jacob Zuma.

Most recently it ruled President Zuma and the government did not follow constitutional requirements in establishing an independent serious crimes unit and in appointing the head of the National Prosecuting Authority.

The response from the ruling African National Congress government has been that the court has become politically activist.

Audit

So now the government has announced an audit of court decisions to determine if the court is following its constitutional mandate to advance a fair and equal society. The audit will also cover rulings from the Supreme Court of Appeal.

De Vos says the constitutional court can stand up to an honest scrutiny.

“I think any serious and honest assessment of the constitutional courts judgements will show that it has actually been quite progressive in advancing social justice issues and that perhaps more so than the government itself, it has been on the side of the marginalized and the dispossessed,” De Vos said.

But Zuma's government isn't happy and academic de Vos says that hovering in the background is the personal interest of Zuma and that this should never be underestimated. Zuma has advocated for an amendment to the constitution to remove the power of the constitutional court to review government policies and actions.

Supremacy

De Vos says this would gravely undermine the rights guaranteed in the founding law and change South Africa’s system of democracy to one of parliamentary supremacy.

“All these things that make a democracy work properly [are] then at the behest of the majority party in parliament, who can infringe and take away any of these rights that will -make it,- diminish the democracy at best, and at worst will completely hollow out the democracy,” De Vos said.

De Vos says constitutional supremacy is one of the founding principles which can only be changed by a 75 percent majority in the national assembly. At present the dominant ANC currently has a majority of 65.9 percent. Observers such as Mckaiser say that in the foreseeable future it is unlikely the ANC will attain sufficient voter support to reach even 70 percent.

“The government will never have in our lifetime again, it would be extremely, extremely unlikely, I’m prepared to say never again, to have a majority as high as up to close to 70 percent, so they will certainly not muster 75 percent within the national parliament to be able to make changes to the foundational elements of the constitutional text,” McKaiser said.

However if at any time, the president of the day was able to capture the court by appointing a sufficient number of judges sympathetic to the dominant party, it would be technically possible for the court to diminish or even disallow its current oversight role.

Expert Pierre de Vos says that now this is unlikely to occur. But he and others warn that if it were to happen it would be tantamount to abrogating the promise made by Mandela in 1996 when he said that the rights guaranteed in the constitution must “be enshrined beyond the power of any force to diminish.”

Constitutional changes in African countries within the last few years:

| - Burundi in 2005 to outline power-sharing arrangements between ethnic groups. |

| - Chad in 2005 to eliminate presidential term limits; move benefits President Idriss Deby. |

| - Uganda in 2005 to establish a multi-party political system and eliminate presidential term limits; latter move has benefited President Yoweri Museveni. |

| - Cameroon in 2008 to remove a presidential two-term limit; move benefits President Paul Biya. |

| - Angola in 2010 to provide for direct election of the president and national assembly, and to spell out presidential powers exercised by longtime leader Jose Eduardo dos Santos. |

| - Guinea in 2010 to allow new elections after the toppling of a military junta. |

| - Kenya in 2010 to include a bill of rights and de-centralize political power; change followed deadly post-election violence in 2008. |

| - Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011 to eliminate run-offs in presidential elections; the system helped Joseph Kabila win re-election in November. |

| - Equatorial Guinea in 2011 to impose a presidential two-term limit, remove a presidential age limit, and create a vice president's post -- changes backed by President Teodoro Obiang Nguema. |