A longtime editor of a magazine that specializes in global power politics recently put forth a scenario where China would stage a takeover of North Korea, giving Washington and the rest of the world a nuclear weapons-free Korean Peninsula.

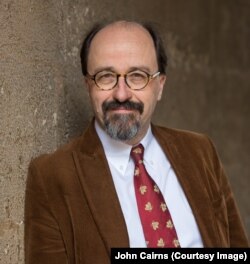

Bill Emmott, the former editor-in-chief of The Economist magazine, said such a move by China would not only gain Beijing a solid foothold on the Korean Peninsula, but also the opportunity to strengthen its own geopolitical position, enhance its global power status, perhaps even the ability to claim the reputation of a peacemaker.

That is the “least bad military option” vis-à-vis North Korea, Emmott said, in that it would avoid subjecting U.S. allies in Asia, including South Korea and Japan, to North Korea’s retaliation that could potentially devastate large parts of South Korea.

China’s takeover of North Korea, as Emmott sees it, would put North Korea “where the country’s post-Korean War history suggests it belongs: under a Chinese nuclear umbrella, benefiting from a credible security guarantee.”

He also said he sees incentives for North Koreans to go along with the plan: “Whereas a nuclear exchange with the U.S. would mean devastation, submission to China would promise survival, and presumably a degree of continued autonomy.”

Emmott said this strategy could win over a majority of North Korea’s military, “except those closest to Kim.”

Biggest winner: China

The biggest winner from such a takeover, however, would be China, he said.

“Not only control of what happens on the Korean Peninsula, where it presumably would be able to establish military bases, but also regional gratitude for having prevented a catastrophic war,” Emmott said.

In addition, a successful military campaign would bring China “huge reserves of soft power,” such as the ability to influence future events in the region and worldwide, he said.

Washington’s desire to ensure that North Korea does not possess nuclear weapons presents China, which many argue is America’s foremost geopolitical rival, the best opportunity to achieve greater strategic and power parity with the U.S. in the Asia-Pacific region, while removing, in Emmott’s words, “a source of instability that threatens both Washington and Beijing.”

Emmott acknowledges that “any military intervention, Chinese or otherwise, would carry huge risks.”

Some scholars put the question bluntly: How does China take over North Korea without being nuked itself?

Problems with the scenario

Emmott posits his thesis of a Chinese takeover of North Korea on the latter’s desire for “some sort of credible security guarantee in exchange for curtailing its nuclear program” while not risking total destruction.

Others suggest China’s neighbor to the east might value independence more than a security guarantee, especially from neighbors along its border.

Evans J.R. Revere, a senior foreign policy fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank, told VOA: “I cannot imagine North Korea ever acceding to the notion of Chinese dominance, particularly of the form that the author describes.

“Say what you will about North Korea, the essence of its approach to the world is its fervent, fanatical nationalism and its race-based belief in the superiority of its system,” said Revere, a former State Department official who has traveled to North Korea over a half-dozen times.

While China and North Korea have been described as allies who at least at one time enjoyed “lips and teeth” relations, meaning one of interdependence, Revere points out that anti-Chinese sentiment in North Korea “runs deep.”

“North Korea’s hypernationalism has been deeply ingrained in the society and political culture at all levels, so it would be hard to imagine any significant group of people in the country who would be receptive” to the notion of domination by the Chinese, or any other country, he said.

Suspicion and resentment of outside influence by key neighbors such as China and Russia are not a new phenomenon, Revere added. He pointed to Kim Jong Un’s grandfather, the country’s founder.

“Kim Il Sung purged the pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese Koreans during the mid-1950s,” he said, adding that declassified material from the archives of the former Soviet Union “also point to significant debates, rivalry, and even political warfare between the North Koreans and the Chinese during the Korean War.”

North Korea’s contingency plan

Geoff Wilson, a retired U.S. naval intelligence officer and China specialist, said he “seriously doubts that Kim, the leader of the most paranoid country on earth, does not have a military contingency plan to deal with a Chinese attack.”

In addition, Wilson told VOA that one cannot conceive of a Chinese takeover of North Korea without a huge number of casualties, “unless the Chinese have a North Korean traitor in hand who can stay Korean defenses while the PLA [the Chinese People’s Liberation Army] rolls down the peninsula.”

Meanwhile, Revere, the former State Department official, also pointed to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s purge and eventual execution of his uncle, Jang Song Thaek, in 2013, and the alleged state assassination of his half-brother, Jim Jong Nam, earlier this year. The deaths of both men, who were known for their close connections to Beijing, were seen as demonstrations of the North Korean government’s absolute intolerance of any potential Trojan Horse.

Concern for the spread of illiberalism

The downside of this idea being carried out is the loss of status by the United States, as well as freedoms, in Asia, Emmott told VOA.

The Fate of the West: The Battle to Save the World’s Most Successful Political Idea, published earlier this year and written by Emmott, is among a rising number of books and articles expressing concerns of the rise of illiberalism in the world.

China’s enlarged footprint, so long as China remains a communist regime, remains a serious source of concern for democratic societies, as well as for those in and outside of China working to change the country.

Curious remark

In Washington, U.S. President Donald Trump on Thursday hosted a gathering of top military leaders and their spouses at the White House, describing the event as “the calm before the storm.” When reporters asked the president to elaborate on “the storm,” he simply said: “you’ll find out.”

Trump was asked several times Friday to clarify the remark or acknowledge if it was in regards to North Korea, but he simply stuck with his “you’ll find out.”

Asked by VOA where the storm was headed, some U.S. analysts, who requested anonymity, said they think Trump was referring to North Korea.

Trump’s former adviser, Steve Bannon, had said in an interview before he left his White House position that because of South Korea’s proximity to North Korea, a military option for Washington doesn’t exist.

“Until somebody solves the part of the equation that shows me that 10 million people in Seoul don’t die in the first 30 minutes from conventional weapons, I don’t know what you’re talking about, there’s no military solution here,” Bannon said. “They got us.”

While current U.S. officials have consistently not ruled out a military option against North Korea, Washington is also exploring diplomatic solutions.