Daixy Aguero holds her chin up when students wander by and are surprised to find their teacher selling makeup at a weekend Caracas street market. Aguero says it's the only way she can make ends meet on a teacher's pay in Venezuela.

Some 40 percent of Venezuela's teachers have left their schools in the last three years, according to a union representing educators. They're escaping low pay and crumbling classrooms.

Others like Aguero have stayed behind on the front line of the country in crisis.

They keep teaching out of a passion that first drew them to education, while taking side gigs to feed their families. Aguero tells her kindergarten students who find her hawking lipstick, eyeliner and face cream that she's not ashamed.

"I tell them you have to work," she said. "And you have to study."

Thousands of Venezuelan teachers vented their frustration in a two-day strike in late October to demand better working conditions such as fair wages and urgent repairs to crumbling schools. Teachers in 17 of Venezuela's 23 states walked out of class, gathering by the hundreds at some protests, while organizers said others stayed in the classroom, fearing they would be punished or fired.

Protesters in Caracas carried banners outside the Ministry of Education blasting President Nicolas Maduro, who they say has let the country down as well as its next generation, which they say doesn't get a proper education.

"We are mobilized to defend the quality of education for our students" said Griselda Sanchez, a representative of the Trade Union Coalition. "We're defending a salary that will allow all of us to live with dignity."

Crisis has driven an estimated 40 percent of Venezuela's 370,000 active teachers from their jobs since the start of 2017, according to union figures. Many are among the more than 4 million Venezuelans who have left in search of a better life.

Despite drawing on the world's largest oil reserves, Venezuela today produces less than 20 percent of the its peak crude production when the late President Hugo Chavez launched the socialist revolution in 1999.

Opposition leader Juan Guaido's U.S.-backed effort to oust Maduro, Chavez's successor, so far has failed to budge the socialist president, who maintains a tight grip on power with support from the military and dozens of international allies including China, Russia and Cuba.

As the political struggle continues with no end in sight, teachers and school administrators say their classes shrink, supplies dwindle and the pay barely covers the basics at home.

New teachers earn a minimum wage equal to a few U.S. dollars a month, though pay doubles and triples with years of experience.

A week after the October strike ended Venezuela's Minister of Education Aristobulo Isturiz spoke in a nationally broadcast press conference about the socialist party's progress uniting workers, but he did not mention the teachers' strike or their grievances.

Officials recently hiked Venezuela's minimum wage and bonuses by more than 350%, bringing it to the equivalent of $15 a month. But analysts say hyperinflation will quickly reduce it to a fraction and leave workers again struggling to afford basic items. The International Monetary Fund estimates Venezuela's inflation will hit 200,000% this year.

"This is the only country where no one is happy when there is a salary increase," teacher Maria Carrillo said. The teachers demand between $500 and $600 a month.

It's not just teachers missing from classrooms.

Erika Tortosa, the principal at Jerman Ubaldo Lira public school in the Minas neighborhood of Caracas, said that five years ago, she had 1,000 students crowding into the hilltop campus. Now, the school has about 200 pupils as families have emigrated.

To cope with shrinking numbers, the school eliminated fourth grade two years ago, sending the remaining students of that grade to a neighboring school. Then, last year it did away with fifth grade, and this year Tortosa said she has no sixth grade.

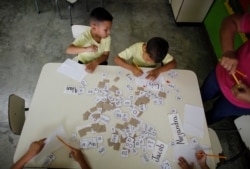

Teachers say broken desks leave students without a proper place to study, while the lights often don't work and campuses don't have consistent water services — troubles shared by residents across much of the country.

Tortosa also has trouble finding enough teachers.

"A lot of teachers have fled the country," she said. "Not everybody, in reality, can endure this situation in crisis that we're living at this moment."

Aguero, 56, said she's forced to sell makeup despite making double the monthly minimum wage because of her years on the job. Her salary falls far short of covering her grocery list, she said. Basic items, like jar of mayonnaise or bottle of juice, can cost the equivalent of $2, quickly devouring her teacher's pay.

So, she wakes up early on the weekends and pulls a heavy backpack onto her shoulders with her son's help. She lugs the cosmetics and her portable table to the market.

The extra work allows her to bring home considerably more than teaching. It's is worth it when she's back in class with her students, she said.

"This is our reality," Aguero said. "Despite that, we keep going to work, and we love it and we work hard."