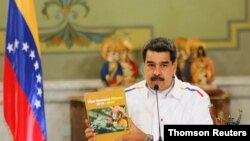

Major European nations are considering imposing sanctions on Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro and several top officials for their recent crackdown on political opponents, although divisions remain over the timing of any action for fear of derailing a negotiated exit to the country’s crisis, The Associated Press has learned.

The financial and travel restrictions are being mulled by a core group of five nations — U.K., France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands — before being proposed to the European Council, said diplomats and members of the Venezuelan opposition with knowledge of the plan.

A total of five sources spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to discuss the deliberations publicly.

While Maduro is among a dozen officials who could be hit with sanctions, no final decision has been made, two people said. The group still needs to breach internal divisions before making a formal proposal to the EU’s executive branch.

Greater consensus exists for punishing top members of the armed forces and judiciary who have been instrumental in the arrest of allies of opposition leader Juan Guaidó, including Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino, whose family is believed to live in Spain. Also on the list is Communications Minister Jorge Rodríguez, a top Maduro aide and envoy to talks with the opposition sponsored by Norway, and Jorge Márquez, who is head of the powerful communications regulator which was responsible for pulling the plug on Spanish broadcaster Antena 3 and Britain’s BBC earlier this year.

Steady progress is being made on building a solid legal case for the restrictions, but the main obstacle is the uncertain impact it could have on a mediation effort by Norway between representatives of Maduro and opposition leader Juan Guaidó, the sources added.

“Our priority is not to impose new sanctions. But neither is it to relax pressure on members of the Venezuelan government,” said a Spanish foreign ministry official. “The primary focus at the moment is the dialogue in Norway.”

After two rounds of meetings in Norway, the opposition had not agreed by Saturday to a third round scheduled to begin next week in Barbados, three diplomats told AP. Guaidó, who has been recognized as Venezuela’s interim president by more than 50 countries, including most EU members, has pledged not to return to the negotiating table until Maduro is ready to call early presidential elections.

The Swedish government also confirmed Friday that it hosted talks this week between major powers with interests in Venezuela. The talks in Stockholm were not attended by either side in the Venezuelan power struggle but did include diplomats from Russia — Maduro’s main financial and military backer — as well as Enrique Iglesias, the new EU envoy for Venezuela.

Almost two years ago, the Trump administration added Maduro to its sanctions list of now more than 100 Venezuelan officials and insiders whose U.S. assets are frozen and who are barred from doing business with Americans.

But the EU has been slower than the U.S. and Canada to confront Maduro, fearing it could wreck the possibility of a negotiated solution to the political stalemate that has exacerbated misery in a country where more than 4 million people — almost 15% of the population — has migrated in search of work and food abroad. The EU’s cautious approach has drawn criticism from members of Venezuela’s opposition, which believe it gives oxygen to Maduro’s government.

One factor now influencing the EU’s consideration of sanctions is the Venezuelan government’s recent political crackdown — in which the deputy head of the opposition-controlled congress was arrested. Another 18 lawmakers have been stripped of their parliamentary immunity from prosecution.

Maduro has argued that the crackdown was focused on lawmakers who backed a failed April 30 military uprising which Guaidó has said was an attempt to restore Venezuela’s democracy.

The EU, which is trying to pave the way for free and fair elections while guaranteeing the delivery of humanitarian aid into the country through the International Contact Group, has not ruled out sanctions in its public statements. Any EU sanctions would require the support of all 28 of the bloc’s members, four of whom — Italy, Greece, Slovakia and Cyprus — don’t recognize Guaidó as Venezuela’s rightful leader. Britain has been the strongest advocate for sanctions.

“The political timing of the sanctions is important and that’s what makes any consensus difficult at the moment,” a top European Union diplomat said. “But that could change very quickly if the Oslo talks fail or if new arrests take place in Venezuela.”

In addition to an arms embargo and export ban on police riot gear since 2017, the European Council has already frozen the assets of 18 people and banned them from traveling to the bloc’s territory. Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez and socialist party boss Diosdado Cabello are among those who have previously been sanctioned, but until now the EU has refrained from targeting Maduro himself.

The opposition is trying to persuade the EU to adopt the new sanctions to pressure Maduro to agree to a fair and transparent presidential election overseen by international observers. It argues that U.S. sanctions were instrumental in forcing several insiders to switch loyalties and support the military uprising.

Underscoring that strategy, Lilian Tintori, the wife of prominent Venezuelan opposition activist Leopoldo López, on Friday met with Spain’s foreign minister and called on the country and the EU to tighten restrictions and increase “pressure on the cruel dictatorship of Nicolás Maduro.”