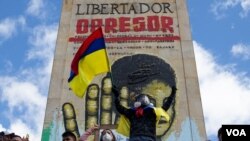

Tens of thousands of people once again were in the streets across Colombia on Tuesday in anti-government demonstrations. The widespread demonstrations came as the government unveiled a new version of an unpopular tax reform plan that sparked initial protests in April, but observers say they point to long-spanning political turmoil in the South American country.

Violence surrounding strikes earlier this year left at least 34 people dead, and scores went missing in the clashes.

This time, it was unclear how many people were injured in clashes between demonstrators and police.

The "Paro Nacional," or National Strike, that began in late April was an outcry against an unpopular tax reform bill and economic turmoil caused by the pandemic. It soon exploded, though, as backlash to a violent state response to largely peaceful protests.

Those tensions surfaced once more Tuesday on the streets of the capital, Bogotá, and other cities across the country, including Cali and Medellín.

Yellow, blue and red Colombian flags dotted the crowds in Bogotá to commemorate the country's Independence Day, July 20, as groups of marchers chanted "Dónde están los desaparecidos?" or "Where are the disappeared?"

Among them was 19-year-old Michelle Calderón, who carried a bicycle helmet to protect her head, and whose face was covered by a Colombian flag bandana reading "RESISTENCIA," Spanish for "resistance."

"They say they don't have money," Calderón said. "But they have money to make war. There's no money for health services — for education, unemployment, but there's always money for tanks, for guns, for bullets."

This new round of marches also ended in violent clashes between police and protesters, although fewer incidents than earlier this year.

Still, by the end of the day Tuesday, clouds of tear gas hovered over where Calderón stood hours earlier, and the sounds of clashes between police and protesters echoed in the streets of the country's capital.

In April and May, the government of right-wing President Ivan Duque made a number of concessions to protesters, including withdrawing the tax reform proposal and promising small reforms to national police, including human rights training for riot police.

As Colombians revived their street protests, Duque's government submitted a new version of the controversial tax reform legislation to Congress cutting a number of unpopular facets, like taxing basic food staples and placing a higher tax burden on companies.

Deeper problems

But critics call those concessions minor and say they fail to address Colombia's deeper problems.

Ariel Ávila, deputy director of the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation research group, said the protests have continued because the underlying problems that fuel discontent in Colombia remain.

"They've achieved important things, but the structural problems haven't gone away," Ávila said. "But the people are protesting because there's no food, people are marching because there are no jobs. That hasn't changed."

The South American country has been locked in political and social tensions for years. Much of that anger has come from failures by the Duque administration to implement historical peace accords signed in 2016 by the previous government, a political adversary.

As a result, violence by rural armed groups in Colombia came roaring back, fueling the first "Paro Nacional" in 2019, one of the biggest mass-demonstrations the country had seen in years.

That discontent only festered in the pandemic as poverty, unemployment, rural violence and political polarization rose across the board, leading to this year's protests.

"We're tired of all the same," said 31-year-old Jhomman Montiel, who leaned on his bike among a crowd of thousands of people. "We're tired of having to come out, to demand that we live better, because the only people who live well here are a small few."

Crackdown

The security forces' response to demonstrations has drawn criticism from international rights groups. In early July, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights accused the Duque government of "an excessive and disproportionate use of force" against civilians.

In the face of criticisms, the Duque government considers the violence a product of what his administration labels as "terrorist" protesters and armed groups seeking to stir chaos.

Officials began a crackdown before demonstrations had even begun Tuesday. They arrested a number of younger protesters who had previously skirmished with police and announced they would seize protective gear like shields, helmets, goggles and respirators from demonstrators.

"We will not allow violent people to once again rob Colombians of their peace," tweeted Colombian Defense Minister Diego Molano Aponte, with a photo of arrested protesters.

Yet, teenage protester Calderón was still among many who kept a helmet with her, explaining she was scared what could happen if she didn't protect herself.

"You're scared that they disappear you and that no one ever finds you, that they'll kill you or, in my case, that they'll rape you," she explained, referring to reports of sexual violence perpetrated by riot police.

As protests gained traction in the afternoon, largely peaceful demonstrations were met with tear gas by packs of police on motorcycles and heavily armed riot police. In Bogotá, tanks rolled through streets filled with people and sprayed protesters with fire hoses, while videos in Cali and other major Colombian cities show similar violent scenes.

Slow churning crisis

Still, Elizabeth Dickinson, Colombia analyst with the International Crisis Group, is quick to note that the Colombian security forces had clearly learned a lesson from sharp criticisms of their previous shows of force.

Dickinson told VOA she expects to see the crisis persist until upcoming elections in May 2022, largely because of a lack of a "significant or substantive response" by the Duque administration to protester demands.

She worries that continued protests also could provide armed groups opportunities to latch onto security vacuums and fuel more violence in the country.

"What I think we're going to see in the next months is a slowly churning crisis, which is dangerous," she said.

Meanwhile Calderón and many other protesters said they planned to continue protesting.

"The younger generation, we're the change," Calderón said. "And if we don't do anything, we're going to continue with more of the same. If we don't come out to march, who is going to defend us?"