Protests against police violence in Colombia have left at least 13 dead and hundreds wounded after police and protesters clashed in major cities across the country.

The demonstrations were triggered after a video surfaced showing two officers in the capital, Bogotá, pinning down and repeatedly tasing 46-year-old lawyer Javier Ordóñez. Police say Ordóñez was drinking on the street with friends and not following social distancing rules.

In the video, Ordóñez is heard begging, “Please, no more” to the officers. He died later in a hospital after suffering nine skull fractures.

As protesters took to the streets in Bogotá, smashing and setting fire to police vehicles and stations across the city, security forces responded.

Videos show groups of officers attacking civilians, and showering them with rubber bullets and tear gas, while others show security forces tear gassing and responding violently to peaceful protests

Most of the dead were young protesters who suffered gunshots wounds. Bogota’s mayor denounced what he described as the “indiscriminate” use of firearms by police.

That violence set off more demonstrations, which expanded across the country.

While international observers have described the protests as Colombia’s “George Floyd moment,” referring to Black Lives Matter demonstrations that emerged in the United States after George Floyd died in police custody in May, many Colombians were quick to dub them as something else entirely.

For Valentina Perez, 20, marching in Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city, it was a response to a trend of violence and frustration that has been building up for months.

“This is nothing new,” Perez said. “In reality, this case had a big impact because there’s an accumulation of anger.”

Perez noted the wave of massacres sweeping rural Colombia during the coronavirus pandemic as armed groups grapple for control, scandals that have struck the government in recent months, and longtime failures by the administration of President Ivan Duque to implement key facets of the country’s 2016 peace accords. The accords ended Latin America’s longest-running conflict, between the government and rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC.

Such frustrations have festered during the country’s five-month-long coronavirus quarantine, which had severe economic and mental health consequences, especially among the country’s poor.

While police violence is certainly a problem in Colombia, said Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis, such violence rarely runs just along racial lines.

Rather, he said this ties more heavily to longstanding trends of impunity among security officials established by decades of armed conflict.

“There's a host of reasons people are protesting, this just caused enough indignation to bring people out to the street,” Guzmán said. “Then when they were met with violence by members of the police, the indignation mounted on top of what was already a lot of angst.”

Similar anger fueled protests which stretched on for more than a month late last year.

While the Paro Nacional, or national strike, drew hundreds of thousands of largely peaceful protesters, the demonstrations that have erupted in Colombia this past week have been smaller, but more violent.

In the first night of demonstrations in Bogotá alone, the government reported that 60 police stations, 91 cars, 77 public buses, five banks and three businesses were damaged. Authorities say a 40-year-old woman was also killed Thursday night after a bus hijacked by vandals hit her.

Such violence has been seen in other parts of the country as well.

Members of Duque’s Centro Democrático party criticized the protests. Party leader Álvaro Uribe, a former president widely credited for returning stability to Colombia after decades of drug violence and civil war – but also known for promoting controversial heavy-handed military tactics – denounced the vandalism and posted videos of torched public buses.

“A firm hand guarantees order, avoids vandalism and the brutality of some police,” he wrote.

Esteban Liscano, 25, was among hundreds of people who clashed with police in Medellín over the last few days. Liscano said he feels the violence is the only way to get their voices heard.

“For all the things that silence represents, violence represents an outcry, making noise,” he said. “It’s something we need for a society that always stays silent, that simply normalizes death,” Liscano said.

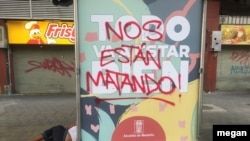

“Nos Están Matando,” or “They are killing us,” is the message written on posters and graffiti lining the walls and vandalized buildings across the country. At the police station near where Ordóñez was reportedly killed, mourners set up a memorial to the victims of police violence.

While officials have called for forgiveness and reconciliation, reactions have been varied among local and national governments. Bogotá Mayor Claudia López has called for police reform and visited victims and their families. At the same time, Duque’s government accused guerrillas and armed actors of infiltrating protests, but offered little evidence to support that claim.

The officers accused of Ordóñez’s killing have been fired. They face charges of homicide and abusing authority.

Guzmán said that while the clashes may not be the “tipping point” that organizers of last year’s protests were looking for to reignite mass demonstrations, they are adding to deep discontent against the country’s leadership.

“This is going to be a buildup,” Guzmán said. “This is not a tidal wave that's going to take over. This is not a tsunami, but this kind of gravitas offers the perfect moment for the next election to start.”