Every Monday through Saturday, residents of Arlington county, Virginia line up with empty bags at 10 a.m. sharp to collect free groceries at a local food pantry.

The recipients include retirees, the elderly, children, chronically unemployed and underemployed adults, the disabled, undocumented immigrants, and the working poor.

"We are dealing with people who live day to day," Charles Meng, executive director of the Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC) said. "We serve about 4,400 families, unduplicated, a year."

According to AFAC's numbers, people of Hispanic descent make up just over half of the population they serve, 10 percent are African-American and the rest are white. Most live at the very bottom rung in the county; no work, no savings and completely dependent, which is provided via referrals from the county.

At the very top of his client-base is the working poor.

"And they can be food insecure, you know, not enough food on the table, once a week, once a month and they are doing bad things," Meng said.

"You know, they are not feeding themselves or their kids."

The poverty threshold

An estimated 46.7 million Americans—14.8 percent of the population—lived in poverty in 2014, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's latest count. Compare that to the year 2000, when the census put the poverty rate at 12.4 percent.

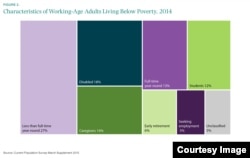

About half of the poor are classified as of working-age adults (18 to 64 years of age).

"A good fraction of those workers are actually employed," said Ryan Nunn, policy director for the Hamilton Project and co-author of a recent joint survey with The Brookings Institution.

To be exact, 13 percent work more than 35 hours a week, 50 weeks a year. Nunn points out that if a person is working a full-time, minimum-wage job, making $7.25 an hour, that person's annual income will fall below the federal poverty line.

"Dating back to the late 1970s, for instance, we know that wage growth for those at the bottom, and even pretty far up through the middle of the income distribution, has been very limited or nonexistent," added Nunn.

But numbers are numbers.

A fixed figure doesn't account for the complexity and complications of working above the federal poverty threshold and still not making ends meet.

Consider Ray, who has a demanding full-time job that pays above the minimum wage, but who lives right on the edge.

"No matter how much I work, I can't make enough," he said.

At 47 years old, Ray is an experienced emergency room technician at Alexandria Hospital in northern Virginia. He asked this reporter to not use his full name to keep his teenage daughter from becoming fully aware of his financial troubles.

He stares down at a cup of stale coffee in a Starbucks nearby, nervously smoothing his thick salt-and-pepper hair as he explains how he got stuck in what he calls his "cash hole," his term for unpaid credit card debt and taxes, the aftershocks of the foreclosure of his townhouse about five years ago and, of course, daily living expenses.

"I pick up extra shifts to make overtime pay all the time," he said. "I just can't get ahead no matter how many hours I work."

Ray estimates he pulls in around $56,000.00 a year, depending on how much overtime he puts in, to support himself, his teenage daughter and his 78-year-old father, who is on disability due to chronic bad health.

That is well below the average median annual income in Alexandria County of $86,775.00.

So, while this employed American works over the standard 40-hour week to earn a stable income, he and his family live without cable television and wireless Internet access in his home, without a computer and drives an unreliable used car.

Family vacations?

"We sometimes drive to Virginia Beach for a day or two," he said. "My Dad isn't very mobile right now, so..." Ray's voice trails off for a moment before he forces a smile.

When asked about the presidential candidates who have promised to address income inequality, he dismisses that as "noise" that he doesn't pay much attention to. He's too busy working, taking his father to medical appointments and raising his child.

"I am grateful," he said. "I am better off than most. You see a lot of situations in an emergency room. I know I'm doing pretty good."