Alexei Navalny, the leading Russian opposition activist who heads the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and the unregistered Party of Progress, was interrogated by police this week, after which his office and home were searched. The police action was connected to a libel case against him brought by former Russian Interior Ministry investigator Pavel Karpov.

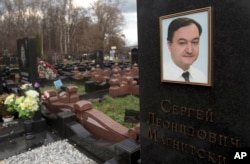

Karpov is among a group of people on whom the U.S. government imposed sanctions for their alleged involvement in the death of Sergei Magnitsky, the Hermitage Capital lawyer who died in a Moscow prison in 2009. The Kremlin's own human rights council said Magnitsky, who was arrested accusing Russian officials of involvement in a $230 million tax fraud scheme, was probably beaten to death.

Karpov filed suit against Navalny on May 19, accusing the anti-corruption activist of slandering him by posting a video that asked how an Interior Ministry officer with a modest official salary could have come into possession of expensive cars and apartments without engaging in corrupt practices.

Navalny has been the target of various criminal investigations and has been repeatedly interrogated. On May 17, Navalny and about 30 FBK members were attacked by a group of men wearing Cossack hats and uniforms at an airport in southern Russia. Navalny accused Russian Prosecutor General Yury Chaika and his son Artem of being behind the attack. Back in December, the FBK published a report linking Artem Chaika to organized crime.

In an interview with VOA's Russian service, Navalny discussed his latest problems with Russian law enforcement agencies.

Q: What happened in the latest incident, and why are Russian law enforcement structures once again putting pressure on you?

A: On the morning of June 1, I was called in for questioning. The interrogation was rather formal. And then, after the interrogation, people entered the office and said, "Hello, we are [from] the criminal investigation department. We are going to search you personally." They patted down my back, lifted up my trouser legs, forced me to take off my shoes, checked to see if I had some terrible secrets in my shoes, and then declared that they were going to search my home.

This was, on the one hand, absurd, of course. Because it's ridiculous: What kind of search can you do in a libel case? The criminal case was launched the same day the libel case was filed: There is no indication of why it was [a] slander [case], what information the policeman Pavel Karpov does not like. ... In general, it's all absurd.

But, on the other hand, there is definitely logic in these actions. The logic is that, on the basis of this ridiculous and trumped up case, it is necessary to take away all the equipment, phones, confiscate all of the memory cards; to rummage through them and find something else. Because the task of the authorities is not even connected to this criminal case, or to defend Pavel Karpov of the Magnitsky List, but to fabricate a criminal case against me and guarantee my non-participation in the [September 2016 Russian parliamentary] elections, against the backdrop of the European Court of Human Rights having overturned earlier fabricated cases, one after another.

[In February 2016, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Russia's conviction of Navalny on embezzlement charges in 2013 was "prejudicial," and that he had been denied a fair trial — ED.]

Q: Pavel Karpov is indeed on the "Magnitsky List" — actually, on two of them, the European one and the American one. Why do you think the Russian state is so seriously protecting those accused of involvement in Magnitsky's death?

A: There has been no reasonable answer to this question. … It had seemed to me it was protecting them because, first of all, America is giving them a hard time, because some foreign senators adopted an act against Russia, so that means [they] have to protect them no matter what, even if they are notorious crooks. This is what I thought before the [Panama Papers] documents were published, which prove that the offshore accounts of the cellist [Sergei] Roldugin, who is an obvious "corrupt coffers" for Vladimir Putin, also received money under this scheme [i.e., the one uncovered by Magnitsky — ED]. These same firms and persons were involved.

[In late April, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, which was involved in bringing the Panama Papers to light, reported that Roldugin, a friend of Putin's since the 1970s, "received money from an offshore company at about the same time it was being used to steal money from the Russian government in the notorious Sergei Magnitsky case." — ED.]

I'm certainly not trying to say that the murder of Magnitsky was carried out so that Putin could receive more money — he doesn't need it. It's just that there is a unified money-laundering infrastructure, or that [they] overlap. So, it turns out that the people who stole 5 billion rubles from the budget [which Magnitsky uncovered — ED], also replenished — fully or partially, we do not yet know — the Putin coffers. Therefore, the mechanisms that protect Vladimir Putin personally are involved here.

Q: What do you call a system that is part of the state — in fact, it wears epaulettes — while, at the same time, according to [Hermitage Capital CEO] William Browder, it is involved in a rather interesting way of making money?

A: There is an excellent word, known to everyone — "mafia." This "mafia" system is a merger of bandits and the state. It is a system that is built in part on family ties. Their children are already inter-married. Loyalty is based on the fact that these people grew up together since childhood, the same way it happens in the real mafia. So you have these people who grew up together, the way Roldugin grew up with Putin, [and who are] loyal [to each other]. This perfectly describes the system as a mafia. It is honed mainly to receive benefits for making money, but if, as a collateral effect, it is necessary to kill someone, it kills people.

Q: Was the latest criminal case against you launched because the authorities sense the previous ones failed, or simply because the system will never leave you alone?

A: In as much as this is being done very deliberately and very crudely, it is, of course, a signal to a certain circle of people that, look, nothing distracts us and we won't let up. But more generally, of course, it is the practical implementation of a political decision that I should not be allowed to participate in the elections. And, in general, that no independents should be allowed to run, and that to prevent us from participating in the elections, they will bring criminal cases against us. This concerns not only me. A lot of people — my colleagues from both the Party of Progress and the Anti-Corruption Foundation — can't run for office because they were put on probation, and several are in jail or political exile. A decision was made, and I'm trying to derail this decision from a formal point of view by having it overturned by the European Court of Human Rights, where I win. But they're simply inventing new cases.