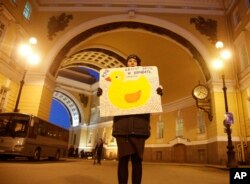

Russian opposition leader and anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny recently caused a stir on the internet with a documentary-style video about the lifestyle of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev that has already been viewed millions of times.

According to the 50-minute film, Medvedev owns palatial mansions, yachts and even foreign wineries. Navalny says even though Medvedev's lavish assets are technically registered to close friends, they are, in fact, his own private treasures.

Legal experts have already weighed in, saying although the evidence would normally make for an effortless corruption indictment in Western courts, Medvedev hasn't violated key Russian statutes.

Navalny isn't convinced. He says the probe offers a sound foundation from which to launch criminal cases.

Medvedev has dismissed Navalny's video. "It's senseless to comment on propaganda attacks by an oppositional convict who's already canvassing for votes and fighting the regime," said the Russian prime minister's press secretary, Natalia Timakova, in a recent statement to Interfax that didn't address corruption allegations directly.

Navalny says he will run in next year's Russian presidential election, even though he was found guilty of embezzlement in a February trial that he and his supporters call a politically motivated prosecution. That verdict effectively barred him from running.

In his first long-format English-language interview since the documentary was released, Navalny tells VOA's Russian service why fighting corruption is the core of his political campaign, and why off-the-books extravagances are a kind of political prerequisite for ascending the highest echelons of Russian power.

QUESTION: What could your audience learn from your foundation's probe into Dmitry Medvedev? What are the key findings you and your colleagues have arrived at while investigating?

ANSWER: I think that the big story in our probe is not the fact that such high officials own that much property but that we've been able to uncover that. For many years — and it's not just what I say; many are aware of this, I think — corruption has been the foundation of [President Vladimir] Putin's regime. Corruption is the backbone of this political hierarchy. Putin's "social contract" with those in power is based on precisely that: You give me your political loyalty, and in exchange, you can steal as much as you want. That's why it's an obvious and well-known fact that all Putin's friends have become millionaires and billionaires. Newspapers talk about that, Forbes ratings confirm that. The thing is that many perceived Medvedev as just someone who is more into some [electronic] gadgets. But we've proven and shown that, in fact, he is no different than others in Putin's near circle. In fact, he is an avaricious man who is obsessed with property, yachts and some idea of a life of an Arab sheik.

Q: But perhaps in the circle that Putin created during his 17-year tenure, it is customary to own such property and income, gained through these specific means? Could it be a kind of symbol of some sort of fraternity, of belonging to this circle?

A: Are you asking whether you need to shoot someone in the head to join a gang, as they do in mobster movies? I feel like some of this, certainly, is there. If you want to make the grade — be a member of this group — naturally, you have "to get your hands dirty." They are all in this together, including corruption. Besides, it's important to remember that it is really a small circle of like-minded people from their times in the St. Petersburg mayor's office, where they were running small scams, like trading precious metals, and where they were directly tied to the organized criminal groups, to St. Petersburg mobsters. But I don't believe that just owning a palace is important to enter the group. More likely, it's the reverse. There is so much money that you have to do something with it. And how else are they going to spend it in Russia? So, that's how they spend it — by building palaces. They are spending it in line with their idea and concepts of a beautiful life.

Q: In other words, you can belong to the group without the riches?

A: I don't think that someone held a gun to Medvedev's head to make him buy these palaces. You can be in the circle and have billions in cash somewhere in your bank accounts, but you can also invest a part of those billions in palaces. It's just they consider it de rigueur to build those things. We see that it's typical for all of them: Putin built in [the Black Sea town of] Gelendzhik. … This is, in fact, as I see it, an important symbol of them playing a game of being "Russian noblemen and aristocracy." They consider themselves the reincarnation of an aristocracy that is created around an absolute monarch. And an important element in their understanding of this aristocracy are all these "ancestral estates," palaces, columns, various Greek-style caryatids.

Q: Do you believe there is anyone in Putin's circle who did not, as you put it, "get their hands dirty"?

A: Of course not. There are no such people. If there ever were, they fell off along the way. From the beginning, it was a group of cynical Soviet crooks who were running their scams at the mayor's office in St. Petersburg. If we look at these people's careers — Putin transferred to the presidential administration while working under Pavel Pavlovich Borodin [who headed the Kremlin's property management department under President Boris Yeltsin], who was also one of the personifications of corruption in the '90s. It means these people were involved in doing all of this for more than 20 years within their group. Of course, not only is there no one who is untainted there, but there is not a single person there who is not 100 percent "dirty."

Q: If they, as you put it, consider themselves a new aristocracy, then what, in their minds, should society as a whole look like?

A: The way I see and understand their actions, they are quite cynical. For public consumption, they always talk about … "the Russophobia of the West," but the main Russophobes in Russia are the ruling elites, who consider the Russian people brutes and rubes who don't understand anything, don't know anything and will always remain silent. And it doesn't matter how openly and blatantly you're stealing from these people — they will always remain silent, no matter what. And it makes perfect sense to steal all their money, since they will otherwise squander it all on vodka. They believe that it is … a country of people doomed to live in poverty because they are too dumb to protest. And it can all be done openly, as long as there are some sensible precautions … primarily, full censorship of the media, and secondly, control of the political system so that no outside candidate is allowed to run for elections.

Q: What can shake Russian society out of its passivity toward corruption, if it doesn't react to the most outrageous information?

A: We need to keep trying, keep doing it. We know that there are people in Russia — a lot of people — who believe that we must react, and they do. OK, today the society isn't very sensitive to these concerns. For 25 years, they witnessed absolute corruption during the "democrats" [of the 1990s], during the Putin regime, and prior to that, during the final years of the Soviet Union. There was heinous corruption in the Soviet Union. That's why, essentially, there is such a high level of tolerance, but it doesn't mean that we have to endure it and stop trying. We are spreading all this information; we're talking about it again and again. At least I try to represent the part of our society that cares.

Q: Are you concerned that in preaching "end corruption and things will be good," you are putting off people who see this as reminiscent of the Soviet-era "fight against stealing socialist property"?

A: I'm not concerned because I'm running for president [in 2018] with an extensive agenda. Obviously, I keep talking about corruption because it has been the main focus of my investigations, my professional career, in recent years. I really believe that corruption is the main obstacle to growth, including economic growth. But in the fight against corruption, I offer political solutions. I'm not talking about jailing six specific people — Medvedev and his friends. I'm saying that it's impossible to curb corruption without independent media, a competitive political system and transparent, fair courts. And this is where I stand out.

Q: But at least free media existed during Boris Yeltsin's presidency.

A: During Yeltsin's presidency, the horrible political mistake made that didn't allow Russia to transition to a path of democratic development was that no systemic political measures were taken so that the state itself would be built to fight corruption. For example, the judiciary system under Yeltsin remained in place from the Soviet era. The same people still adjudicate in the same courts. Yeltsin, unfortunately, couldn't guarantee freedom of the press. I'm talking about these things and trying to give you a comprehensive picture of this problem.

Q: Has the fact that you released your investigative video during your trip to Russia's regions to open up local electoral offices affected your campaign? Do people ask you about the film?

A: It absolutely has. Seven million people have watched the video on YouTube, more than 2 million have watched it on Odnoklassniki [the Russian social media site]. This means we've reached about 9 percent of the country's population and far more than 9 percent of its voters. We feel like the film has reached beyond the usual audience of political activists and provided information about myself and the campaign. Based on people's feedback and the number of volunteers who are registering, and simply people who stop me down on the street, we see that the film is playing a big positive role in our campaign.

Svetlana Cunningham translated Russian language interview into English.