BEIJING —

Researchers studying the health impact of China’s air pollution say that people in the south of the country are living on average 5.5 years longer than their counterparts in the north.

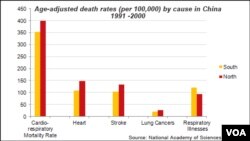

Using health and pollution data collected by official Chinese sources, scientists concluded that decades of burning coal have led to a rise in deaths from cardio-respiratory diseases for people living north of the Huai River - considered the dividing line between northern and southern China.

The academics from the United States, Israel and China concluded that government coal policies in force since China’s Mao era have resulted in higher levels of total suspended particulates north of the Huai River.

Coal winters

Li Hongbin, professor of Economics at Tsinghua’s School of Economic and Management and one of the authors of the study, says that winter heating is a major reason for high emissions in the cold north of China.

"The north of China relies on central heating based on burning coal that originates heavy air pollution. This is one the most important reasons why there’s such a big difference in pollution level between the north and the south” he says.

The study, published on the American journal The Proceeding of National Academy of Sciences, shows that excessive coal burning raises the level of soot, smoke and other airborne particles - the total suspended particulates - by 55 percent more in the northern bank of the Huai River.

Li Hongbin says that “basically, exposure to total suspended particulates level above 100 micrograms per cubic meter reduces life expectancy of about 3 years and increases mortality by 14 percent.”

The Huai River divide

In the aftermath of the communist revolution, the Chinese government started a policy of allocating free coal for boilers that could generate heat during the north’s cold winters.

At the time the demarcation line was set along the Huai River, one of major waterways that runs across Henan, Anhui and Jiangsu provinces in central China.

Today that border is still in place and the country is still burning coal to stay warm.

In addition to central heating, coal has also been used to feed a flourishing government-led heavy industry in northern provinces for decades.

Impact on health

This week’s report is the latest to raise alarms over the health impacts of China’s worsening air pollution.

The Ministry of Environment said last month that only 27 out of 113 major cities met government air quality standards in 2012. And a World Bank report in 2007 assessed that between 350,000 and 400,000 people die prematurely in China each year because of air pollution.

Wang Xinchao, from Beijing-based Ngo Global Village, says that China’s urban residents are becoming increasingly concerned with air pollution and are ready to take action to protect their health.

Although China still relies heavily on coal especially for winter heating, “using coal is not very efficient but the level of pollution coming out of it is obvious. Ordinary citizens need to make a responsible choice about this,” she says.

To some, the growing seriousness of the problem is a sign that the authorities will address it. Wang Xinchao is confident the authorities will be forced to act.

“The impact on city life is so big that from now on we can only see a progress towards its improvement” she says.

Using health and pollution data collected by official Chinese sources, scientists concluded that decades of burning coal have led to a rise in deaths from cardio-respiratory diseases for people living north of the Huai River - considered the dividing line between northern and southern China.

The academics from the United States, Israel and China concluded that government coal policies in force since China’s Mao era have resulted in higher levels of total suspended particulates north of the Huai River.

Coal winters

Li Hongbin, professor of Economics at Tsinghua’s School of Economic and Management and one of the authors of the study, says that winter heating is a major reason for high emissions in the cold north of China.

"The north of China relies on central heating based on burning coal that originates heavy air pollution. This is one the most important reasons why there’s such a big difference in pollution level between the north and the south” he says.

The study, published on the American journal The Proceeding of National Academy of Sciences, shows that excessive coal burning raises the level of soot, smoke and other airborne particles - the total suspended particulates - by 55 percent more in the northern bank of the Huai River.

Li Hongbin says that “basically, exposure to total suspended particulates level above 100 micrograms per cubic meter reduces life expectancy of about 3 years and increases mortality by 14 percent.”

The Huai River divide

In the aftermath of the communist revolution, the Chinese government started a policy of allocating free coal for boilers that could generate heat during the north’s cold winters.

At the time the demarcation line was set along the Huai River, one of major waterways that runs across Henan, Anhui and Jiangsu provinces in central China.

Today that border is still in place and the country is still burning coal to stay warm.

In addition to central heating, coal has also been used to feed a flourishing government-led heavy industry in northern provinces for decades.

Impact on health

This week’s report is the latest to raise alarms over the health impacts of China’s worsening air pollution.

The Ministry of Environment said last month that only 27 out of 113 major cities met government air quality standards in 2012. And a World Bank report in 2007 assessed that between 350,000 and 400,000 people die prematurely in China each year because of air pollution.

Wang Xinchao, from Beijing-based Ngo Global Village, says that China’s urban residents are becoming increasingly concerned with air pollution and are ready to take action to protect their health.

Although China still relies heavily on coal especially for winter heating, “using coal is not very efficient but the level of pollution coming out of it is obvious. Ordinary citizens need to make a responsible choice about this,” she says.

To some, the growing seriousness of the problem is a sign that the authorities will address it. Wang Xinchao is confident the authorities will be forced to act.

“The impact on city life is so big that from now on we can only see a progress towards its improvement” she says.