On June 17, former U.S. first lady Laura Bush penned an editorial in The Washington Post about revelations that the government had separated 2,000 children from their parents.

“I live in a border state,” wrote Bush, who lives in Texas. “I appreciate the need to enforce and protect our international boundaries, but this zero-tolerance policy is cruel. It is immoral. And it breaks my heart.”

In her letter, Bush called for an immediate end to the separation of parents and children.

She also recalled a simple act of humanity displayed by another first lady nearly three decades earlier. In 1989, in the midst of the AIDS epidemic, Barbara Bush, who died in April, visited a residence for families and children with AIDS.

Without prompting, she picked up and cuddled a baby dying of AIDS, a powerful act of compassion at a time of confusion and fear over how the virus spreads.

That kind of compassion, Laura Bush said, exemplifies the American spirit.

Three days after The Post published her letter, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to prevent future separations.

Laura Bush wasn’t alone in condemning the separation of children from their parents. But her voice as a former first lady carried special weight.

Leading by example

Around the world, current and former first ladies play unique roles. They often lack legal authority, but they lead by example, rallying support for social issues, and even shaping foreign and domestic policies.

Cora Neumann is the founder of the Global First Ladies Alliance, a Los Angeles-based organization focused on supporting and connecting first ladies around the world, particularly in Africa.

First ladies have untapped potential, Neumann said. Their influence tends to unfold behind the scenes, but their power is real.

“They’re in this position of power, potentially, and influence,” Neumann told VOA. “But they’re just disregarded. And there was a real double standard there that caught me that I think applies to women specifically.”

Social issues

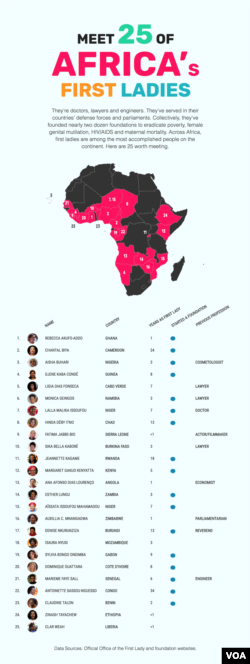

African first ladies gravitate toward complex social problems involving education, women’s health, maternal mortality, women’s economic empowerment and HIV/AIDS.

Monica Geingos, a lawyer and the first lady of Namibia since 2015, has focused on lifting women from poverty through collateral-free loans and training to entrepreneurs.

Kenyan first lady Margaret Kenyatta has led an initiative to bring mobile health clinics to dozens of counties around the country.

Sia Nyama Koroma, who served as first lady in Sierra Leone from 2007 until just last month, created her country’s Office of the First Lady.

A trained chemist and psychiatric nurse, Koroma founded her office to support initiatives focused on education, training and women’s empowerment.

Koroma’s efforts have gone a long way in addressing maternal mortality, Neumann said, especially through work with local populations and traditional religious leaders.

‘Leading without authority’

First ladies often enact change not because of a legal mandate, but by using their platform to inspire action — what Neumann called “leading without authority.”

“What we’ve seen in some of the countries in Africa, and you see here [in the U.S.] in ways as well, is that the first ladies are considered, and sometimes called, the mother of their country,” Neumann said.

“And the ability to shape attitudes and behaviors at [a] local level by going into the communities and meeting with local villagers and local populations can sometimes be more powerful than authority,” she added.

Neumann gave the example of the former first lady of Tanzania, Salma Kikwete, who, along with her husband, went on live national TV to get tested for HIV.

Lifting women

Empowering first ladies and those who work with them elevates the status of all women, Neumann said.

The Global First Ladies Alliance has worked with 45 first ladies. In addition to Africa, the group has convened women from the U.S., the U.K., Latin America and Asia to share experiences and learn from one another.

The alliance documents those exchanges and develops case studies and best practices. That’s led to initiatives such as a fellowship program for first ladies’ senior staff.

“You’re only as good as your best adviser,” Neumann said, and that prompted her team to develop a training curriculum for running an effective office.

Growing influence

Over time, first ladies have gained clout and formed powerful networks to better their countries.

“We’re just seeing first ladies continue to take on more and more of a visible and powerful role,” Neumann said.

First ladies work most effectively when they complement their husbands’ policies, Neumann added, rather than take a public stand against them. But behind closed doors, they’ve influenced policies.

Neumann sees first ladies gaining even more prominence in the future.

“The more powerful they become, and the more visible they become — like we just saw in the United States — this speaking out and applying direct pressure is going to continue to become more important. So we just see the role actually becoming more and more influential,” she said.