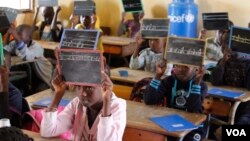

In Alieu Samb primary school, in a working-class section of Dakar, second-graders are learning to read in French.

Like most children in Sub-Saharan Africa, they are taught in their country’s common colonial language rather than in their mother tongue.

Linguistics professor Mbacke Diagne, of Dakar’s Cheikh Anta Diop University, wants to integrate local languages into the standard teaching curriculum.

He says most children entering primary school in Senegal have been functioning in Wolof for at least seven years beforehand.

“They have structured their world in this language,” he says, “but as soon as they get to school, all this knowledge is set aside in order to impose French.”

Diagne and others believe this slows the learning process and can discourage children from pursuing education.

According to Education Policy and Data Center statistics, Senegal’s youth literacy rate is lower than the average for other lower middle income countries, and more than half of secondary school-age children are out of school.

Organizations such as the Associates in Research and Education for Development have been piloting bilingual teaching programs in Senegalese primary schools.

Awa Ka Dia, the ARED Program Director, explained that children start simultaneously learning French and building literacy skills in either Wolof or Pulaar, which are later used as a base to read in French.

ARED currently operates in 98 primary schools spread between Dakar, the northern city of Saint-Louis, and the town of Kaolack. The pilot program ends this year, and Dia hopes results will encourage the government to fund an extended version, covering more regions and incorporating other local languages.

But in Alieu Samb school, Headmaster Meissa Dieng has mixed feeling about teaching in Wolof.

“Speaking French in school will allow children to really master the language,” he said, “but then there is the psychological impact of deconstructing a thinking process that has already been established.”

And parents are often the first to oppose the idea.

Literacy and education expert Chris Darby is with SIL, a nonprofit serving language communities around the world. He says for six years he struggled with community resistance to a multi-lingual education project in rural Senegal.

“A lot of the resistance comes from parents, as well as teachers, and right up the hierarchy,"Darby said. "But parents are very keen, I think, for children to succeed. And they tend to think of success, as far as what a school can do, in terms of delivering an international language.”

Other countries also are delving into local languages. In 2014, the Ethiopian government and USAID launched a reading curriculum in seven Ethiopian languages to improve reading skills. And in 2015, Tanzania introduced a policy to remove English as a medium of instruction and teach entirely in Kiswahili.

SIL Director of Research and Advocacy Barbara Trudell said these changes are necessary and that all children should be taught in their mother tongue. She also points out, though, that favoring local languages in a multi-lingual context can be complicated.

“As soon as you move from an international language down into an African national language, choosing one over the other, the rivalries are instantly there,"she noted. "At least that is the thing about French, English, Portuguese, they’re sort of seen to be on a different level.”

In Senegal, Wolof is spoken by more than 80 percent of the population, but there are more than 20 national languages recognized by the government.

In this context, this may be the greatest challenge to teaching in local languages.