This is Part 5 of a 5-part series: Honoring Africa’s Traditional Music

Continue to Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

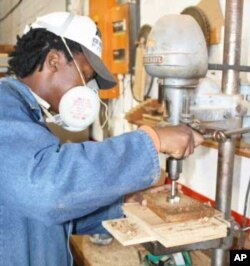

The air is hazy, filled with a powdery wood and metal mist and loaded with the mind-numbing noise of heavy machinery. Sawdust litters the concrete floor of the cold, cavernous factory. Large spiraling horns from kudu antelope and rock-solid beams of African sneezewood lie in piles in corners. Silver slivers of steel overflow from containers on desks.

These are some of the materials used to create a new generation of traditional African musical instruments. The company in Grahamstown, a city in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, is one of the few in the world currently dedicated to the ongoing manufacture of the products.

“My main input into the firm has been to encourage (it) to make traditional African instruments because they’re very scarce in Africa now,” said South African musicologist Andrew Tracey. “Very few people are making them.”

His father, pioneer ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey, spent about 50 years recording music throughout sub-Saharan Africa before his death in 1977. Hugh Tracey started the business African Musical Instruments (AMI) in 1954, as a further way to preserve the continent’s musical heritage.

‘Little noise’ makes big impact

Andrew said his father’s “first mission” at AMI was to invent a simpler version of the Zimbabwean mbira. This 24-note thumb piano, with wooden base and metal keys, is notoriously difficult to play.

After years of experimentation, and about 200 failed models, Hugh Tracey finally unveiled his kalimba. It had fewer notes than the mbira and “corresponded to a Western piano,” explained Andrew. “It has bass on the left and treble on the right like a piano. It uses a left-right, left-right tuning. The keys form a V-shape, and that’s the way a person’s thumbs move; your thumbs rotate. This makes it far easier to play.”

With his invention, said Andrew, Hugh Tracey “wanted the rest of the world to experience the wonder of African music.” He added that the kalimba was an “instant hit” and had remained popular around the world.

“So much so that there’ve been numerous rip-offs down the years, in places like Japan and America and other places, but they’ve always been inferior to ours,” Andrew maintained, continuing, “Most of them don’t have the same sound ours does. Ours is made with the original African wood (kiat) that the mbira players in Africa know is a good sounding wood.”

He also ascribed the unique “subtle, soothing, ringing sound” of the African kalimba to expensive steel used to make the notes. “It can’t be any old steel; it should be spring steel. That gives a quality, a ring, a clarity to the notes that you don’t get any other way.”

‘Quintessential’ African instrument

But, said AMI director Christian Carver, the current “bedrock” of AMI’s business lay in making and exporting African marimbas made from indigenous sneezewood.

“It’s a resonant wood like no other wood,” said Andrew. “It just rings like a bell. It’s a musical wood. It gives the clear sound that you want, because it’s a very hard wood. Saw it and it produces very fine dust that causes violent sneezing….”

AMI’s David Fuller, who tunes instruments for the firm, explained that Mozambique’s Chopi people had for centuries made their xylophones from sneezewood. “They know that if you bake it, it produces a very good ring tone. It really enhances the sound,” he said. “So we learned from the Chopi and we bake our sneezewood. That cures it and also makes it a lot more stable, in terms of its tuning. So we can send instruments all over and they’ll maintain their tuning.”

Andrew said marimbas “suited” Africans, who generally thought about music in “choral” terms. “They love playing music together and all singing together, and the marimba is a wonderful instrument for making music together, big sounds and big bands. A whole group of marimbas tuned differently can sound like a symphony.”

Carver added, “One of the things distinctive about resonated xylophones in Africa is that they all have a buzzer which creates this buzzing sound,” thus ensuring that African marimbas are louder than others.

Andrew insisted that the marimba was a “quintessential” African instrument. “You can adapt (African) urban, township music – popular music – perfectly onto the marimba,” he said.

Carver said that African marimbas were becoming increasingly popular around the world. “There’s a very strong African marimba following on the west coast of the United States especially,” he told VOA.

‘New age’ marimbas

About 10 years ago, Carver, who’s also an engineer and a musician, began “refining” the African marimba. “I started working on the acoustics of the instruments, trying to make them more consistent. I also did a lot of work in finding out whether they would be appropriate instruments for schools.”

He said African children were “particularly attracted” to marimbas, adding, “That’s partly because Andrew Tracey and (his fellow South African musicologist) Dave Dargie developed a different tuning system for the marimba, a system that makes it sound more traditionally African.”

That meant a “more rhythmic, louder, heavier” instrument, Andrew said, that “works much better with traditional harmonies, which are a big part of African music.”

Carver stated that his adapted marimbas “took off pretty quickly. They got into the (African music) mainstream and so (African musicians) produce regular hit records with marimbas on them. They lend themselves very quickly to adapting to any of the cultures in (Africa).

‘Criminally non-existent’ music education

But while established musicians are able to afford marimbas, the instruments remain out of the reach of most African children. According to AMI’s website, its cheapest marimba is currently priced at the equivalent of about US$ 800 and its most expensive, for concert use, is about $2,850.

“The majority of African schools have no budget for music at all. They sometimes have no choir – and certainly no instruments,” said Andrew.

But Carver emphasized that AMI remained dedicated to making marimbas more affordable. “We’re constantly trying to reduce the costs of these instruments. My current project is to produce a very portable and much cheaper set of marimbas that could be used by individuals to go and teach it in schools. This would at least give some African children access to marimbas and maybe open doors for them into music.”

Carver said he was “very aware” of his responsibility to succeed in his quest, because music education in Africa remained “criminally non-existent” in many places on the continent.

He commented, “With current research in education pointing to major advantages for kids who are involved in music from very early on, from better brain development to better social skills to better ability to think outside the box, music should be a major part of the development of school children in Africa.”