Rows of homes line the quiet, narrow streets of Hagerstown's Jonathan Street Neighborhood, with boarded-up storefronts and empty buildings that have been left for decades.

The neighborhood was once a vibrant African-American community, but for years it has grappled with a lack of economic development and racism. Located in Washington County, Maryland, Hagerstown is filled with a rich, dark history dating to the 19th century.

Washington County, between Pennsylvania, a free state, and Virginia, a slave state, was the embodiment of the struggle between pro- and anti-slavery forces back then.

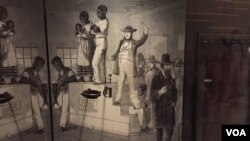

Black men, women and children were sold to white slave owners on the slave blocks on Jonathan Street and at the courthouse.

'Sad truth'

"We did have it; the slave block was here, and stood here for many years. I can't really give you any more on the slave block, because it's just another sad truth of Washington County," said Alesia Parson-McBean, project coordinator of the Doleman Black Heritage Museum.

The close proximity to Pennsylvania led to the presence of escape routes for the Underground Railroad, with Harriet Tubman utilizing the Ebenezer AME Church as one of the stops. With the escape routes came the presence of slave catchers, sent to retrieve runaway slaves who were then returned to their masters or put on the slave blocks to be sold.

With the end of slavery and Hagerstown playing a role for both sides during the Civil War, the Jonathan Street Neighborhood was formed.

Bound by segregation laws that restricted movement and opportunities, African-Americans had to turn inward. They established businesses along Jonathan Street and attained skills to survive and succeed within their confines.

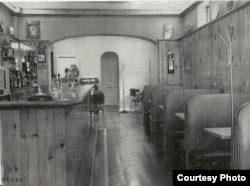

"In the Jonathan Street area ... there were booming businesses, barbershops, restaurants. People would come from out of town just to come to experience the nightlife," said Anastasia Broadus, director of the Robert W. Johnson Community Center.

Harmon Hotel

The Harmon Hotel served as the only establishment in Hagerstown for visiting African-Americans and performers like singer Tina Turner. Notably, baseball player Willie Mays had to stay at the hotel as he made his professional debut in 1950 in the midst of racial discrimination, as his white teammates stayed where he was not allowed.

The boundaries led to a close-knit community that continues today.

"People lived on their skills, and so it made it wonderful growing up," said Parson-McBean. She said it was the kind of community where "everybody looks out for everyone and everybody does something that can sustain you — that's what this neighborhood was all about."

Desegregation enabled African-Americans to spread out. "It was twofold — either they left here to go for education, to become educated, or they left here for a better job," Parson-McBean said. Those who graduated elsewhere, "my sister included, did not come back because they couldn't find a job in their field, and that is still a problem to this day."

Attracted to the peaceful environment, newcomers settled in Hagerstown, increasing the African-American population to 15 percent. They experienced the economic strains as well as racism.

"I moved here in 1994, and the first month that I was here, there was a Ku Klux Klan rally right down the center of one of the neighboring towns," said Jessica Scott, president of the board of directors of the community center. "And coming from New Jersey, up north, I immediately thought I had stepped back in time. People still called us 'colored.' They didn't respect positions and education. So it's been a long road, and they've come a long way, but there's still quite a bit of work to do."

Hope for change

Currently, the city has programs that lump women and minorities into one group; there are no programs that separately target African-Americans. Though the community continues to grapple with many economic and social obstacles, leaders keep fighting for its survival. Those involved with the Doleman museum preserve and share this history and are looking for a permanent home in which to display their rich collection.

IN PHOTOS: African-American History in Hagerstown

Today, leaders such as Parson-McBean, the first and only African-American on the Hagerstown City Council, and Broadus maintain the faith and hope for change.

"The community will stand together when it comes to tough times and what not," Broadus said. "We may not see a lot of people standing together on a daily basis, but if something happens, I believe that everybody in this community will rise up and be united and become one."