This is Part 1 of a 5-part series: Innovations in African Farming

Continue to Part: 1 / 2 / 3 /4 /5

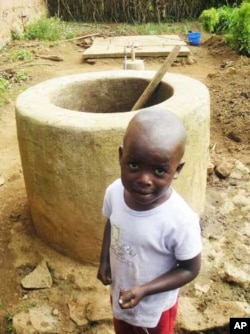

When Danielle Nierenberg set off on a two-year, 25-country tour of sub-Saharan Africa in 2009, she couldn’t help but feel “daunted.” Her mission: to uncover a “treasure trove” of agricultural success stories.

She realized she’d be traveling through a region where more people are chronically hungry – about 265 million of them – than in any other place on earth. And to many in the rest of the world, sub-Saharan African agriculture is synonymous with failure – from overgrazing to soil erosion to massive crop failures because of incorrect planting methods.

Nierenberg, an agricultural researcher, leads the Worldwatch Institute’s “Nourishing the Planet” project, an initiative aimed at easing hunger globally. The Institute, an international anti-poverty group based in Washington, DC, is dedicated to worldwide sustainable development.

African solutions

Nierenberg went to sub-Saharan Africa to find agricultural initiatives that would allow millions of people to feed themselves, without damaging the environment.

Initially, despite her enthusiasm, she expected to be “very depressed and not see a lot of hope” in the region’s agriculture. But, after visiting more than 300 projects in countries as diverse as Niger, Rwanda, Madagascar and Mozambique, she said she felt “warm and optimistic.”

Nierenberg told VOA in an interview in Johannesburg at the end of her journey, “There is so much self-reliance [in Africa] and the people we met with have so much hope for themselves and their communities and their countries. And I have come away with a whole different view of the African continent.”

At the same time she emphasized that she and her team of researchers had not closed their eyes to the “dark side” of Africa. “We saw a lot of bad stuff. We saw the same things that you see on the [TV] news every night – [starving] kids with bloated bellies. We saw lots of hungry people and we saw lots of people waiting in line to get food aid.”

But too often, she said, this is the only side of Africa people see. So she and her colleagues dedicated themselves to highlighting the “really grassroots African solutions that are helping to alleviate hunger and poverty and protect the environment.”

African innovations to feed cities

Nierenberg said the world must learn valuable lessons from African small-scale farmers, who are playing leading roles in urban agriculture, producing food to save millions of people from hunger in the continent’s cities.

In this regard, one of the African innovations her team found is the concept of “tire gardens.” People in various cities are using them to grow vegetables. They cut old tires in half, and fill them not with fertile soil, which is rare in urban areas, but with refuse. The trash provides stability for plant roots and nourishes the crops.

Nierenberg said the development of urban agriculture is of “critical importance” because half the human population now lives in cities. “In sub-Saharan Africa, 15 million people are moving to cities each year. By 2020, some 40 million Africans will depend entirely on food grown in cities to meet their food requirements,” she said.

Nierenberg warned that unless the world’s food system finds innovative ways to feed cities, food shortages and food price riots will increase in the near future.

“Making sure that urban farmers have access to the inputs that they need, and that they’re not impeded by policies and laws in cities that prevent them from growing food, has become vitally important – not only for Africa’s sake, but for the whole world,” she said.

Preventing food wastage

Nierenberg revealed that Africans have also developed innovations to preserve food and to prevent food wastage – both “crucial” issues in a world suffering frequent food shortages.

“Twenty to 50 percent of the [annual] global [food] harvest is wasted before it ever reaches people’s bellies and so, given all the attention that goes into improving [food] yields, the same sort of attention needs to be focused on preserving food,” she said.

According to the African Development Bank Group, more than a quarter of the food produced in sub-Saharan Africa every year – about 100 million tons – rots before it can be eaten because of poor harvest or storage techniques, severe weather, or disease and pests.

Nierenberg’s project highlights ways Africans are preventing this large-scale loss of food. In Zambia, for example, the National Institute for Scientific Research has developed low-cost driers to preserve fruit by dehydration.

In East Africa, many liters of milk go to waste because dairy farmers don’t have access to refrigeration and pasteurization facilities. So the East Africa Dairy Development project is helping farmers in Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda to form cooperatives. This gives them access to “group-owned and -run refrigerated milk collection centers” and facilities where the milk is pasteurized. At market, the farmers get higher prices for the processed milk and consumers get healthier milk.

Young Africans becoming food producers

Nierenberg said it’s common throughout Africa for agriculture to be used as a “punishment, something that kids are forced to do when they’re bad at school, or when they don’t have the option of going to university.”

But her team saw projects on the continent that are “finding ways to make sure that youth are [positively] involved in agriculture and are excited about it and are making money off of it….”

In Uganda, for example, Project DISC [Developing Innovations for School Cultivation] has inspired 1,100 school children so far to grow crops to combat increasing food shortages.

The Worldwatch Institute said teachers and volunteers trained by DISC show the youngsters “how to grow local crop varieties using traditional and environmentally sound methods. Because of their experiences growing, tasting and cooking fruits and vegetables, the children not only begin to appreciate agriculture, they also learn about the importance of eating high-quality and fairly produced foods.”

In “leading by example” by making agriculture an “attractive option” for youth, said Nierenberg, Africans are demonstrating innovations that in the future will result in more people producing more food, and possibly “insulating” the globe against food shortages.

‘A true character…’

Reflecting on her “incredible quest,” Nierenberg recalled meeting some “unbelievable people” in sub-Saharan Africa. She specifically remembers Kes Malede Abreha, an Ethiopian farmer she said was a “true character.”

“He describes himself as a farmer-priest,” she said, smiling.

Abreha was farming in a very dry area of Ethiopia. Nierenberg explained, “His farm was struggling and he wasn’t able to make a lot of money because he couldn’t water his crops sufficiently. But with the assistance of an NGO he developed very low-tech treadle pumps that helped him save his farm.”

A treadle pump is a simple lever device, made out of metal or wood, pressed by the foot to drive a pump that lifts water from underground. “For a lot of people, the idea of these treadle pumps sounds completely primitive,” said Nierenberg.

So, she continued, when Abreha announced to his community that he was going to extract water from a desert, from a place where water had never been found before, and by means of “something that looked like it was from the stone age,” the farmer’s neighbors and even his own family scoffed.

“All of his neighbors thought he was crazy; his wife left him. She was like, ‘There’s no way you’re going to get water on this farm, and he was able to!” Nierenberg said, adding that by using such a rudimentary water-lifting technology, Abreha increased his farm’s productivity to such an extent that he’s been able to build a better house and send his children to school.

“And now he’s become an example of innovation and success in his community, teaching other farmers both water-lifting technologies for their own farms as well as erosion control techniques,” said Nierenberg.

Hopes for investment in African agriculture

Her project’s findings are contained in a recently published book called 2011 State of The World – Innovations that Nourish the Planet. Soon, Nierenberg and her colleagues will brief a variety of African policymakers on their conclusions, and will also speak to members of the United States Congress and the British Parliament.

But she “really” wants to reach the world’s funding and donor community, which she hopes will pour money into some of the “brilliant” African agricultural initiatives she’s helped expose.

“There’s a lot [of good] going on [in African agriculture]. It just needs more attention and more investment and, ultimately, more research to make sure that those innovations flourish,” Nierenberg said.

![International agricultural researcher Danielle Nierenberg [center, in sunglasses] with farmers in Ghana. She spent two years traveling throughout Africa in search of the continent’s environmentally friendly successes in food production](https://gdb.voanews.com/0729A305-F312-4EE9-B0CB-15EDD6434021_w250_r0_s.jpg)