A day after the Ethiopian federal government abruptly suspended nearly eight months of military operations against rebels in its Tigray region, communications with the country's northern region remained sketchy at best, and humanitarians were hopeful the truce would hold so aid could reach the hundreds of thousands of people struggling in famine-like conditions.

"The consequences and impact of the immediate cease-fire remain unclear," U.N. spokesperson Stephane Dujarric told reporters Tuesday.

He said the organization's aid operations have been constrained in recent days because of the fighting but would resume pending a security and access assessment.

"We are looking at supply routes into Tigray in consultation with our security colleagues and logistic experts," Dujarric said, adding that land routes and the airport in Tigray's capital, Mekelle, are closed.

The International Committee of the Red Cross has also temporarily limited its movements outside Mekelle and is monitoring developments closely.

"The situation in the region is very volatile, but Mekelle looks quiet now," ICRC regional spokesperson Alyona Synenko said from Nairobi, where she has been in contact with ICRC staff on the ground. "Shops are open, we see people in the street. Communication networks are down, internet is not working."

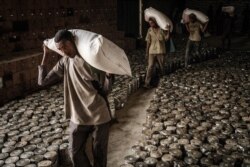

The United Nations says some 350,000 Tigrayans are coping with famine-like conditions because of the fighting. On Tuesday, USAID official Sarah Charles put the number closer to 1 million in testimony to the U.S. Congress.

"Of the 6 million people that live in Tigray, we estimate that 3.5 million to 4.5 million are in need of urgent humanitarian food assistance," she said. "Of these, 700,000 to 900,000 people are already experiencing catastrophic conditions." Without scaled up aid deliveries, she said, "we will likely see widespread famine in Ethiopia this year."

Humanitarian pause

On Monday, the federal government of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed unexpectedly announced it was pausing military activities against the Tigray People's Liberation Front to "help ensure better humanitarian access and strengthen the effort to rehabilitate and rebuild the Tigray region," which it was bombing as recently as one week ago.

Aly Verjee, a London-based researcher for the U.S. Institute of Peace who specializes in East Africa, said that there are two theories as to why Abiy chose this moment to declare a cease-fire, and that the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

"One is that the ferocity of the [Tigrayan] forces' actions has prompted the federal government to resort to a cease-fire," said Verjee. "The second is that the federal government had been planning this, recognizing the humanitarian situation is deteriorating and something needed to be done."

Abiy has been under intense Western pressure to end the fighting. The U.S. restricted economic and security assistance to Ethiopia because of the fighting and imposed visa restrictions on some Ethiopian officials. The European Union has also warned that it is "ready to activate all its foreign policy tools."

What lies ahead?

A senior State Department official warned Tuesday that the country is at an inflection point, and what the parties do now will determine its future.

"If the government's announcement of a cessation of hostilities does not result in improvements, and the situation continues to worsen, Ethiopia and Eritrea should anticipate further actions," Acting Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Robert Godec told a congressional hearing on the situation. "We will not stand by in the face of horrors in Tigray."

Eritrean troops have been fighting the Tigrayan rebels on the side of the Ethiopian military. It is not yet clear whether they have also pulled back or departed.

But the halt in the federal government's offensive does not mean the danger has passed for Ethiopia or the Horn of Africa region.

Cameron Hudson, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's Africa Center, said there are concerns that the country could still break apart along ethnic lines, much as Yugoslavia did in the early 1990s.

"The idea that the Tigrayans are now fully in control of their territory suggests that they are very unlikely to seek a new kind of political union with Ethiopia and will in fact do their best to exert greater autonomy over the region," Hudson said.

He noted simmering ethnic tensions in several other parts of the country, which has a population of 113 million.

"What lesson will they draw from the Tigrayans possibly beating back the government's military, and then exerting greater autonomy for themselves in their region?" Hudson asked.

VOA's Kate Pound Dawson and Jesusemen Oni contributed to this report.