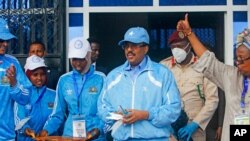

As Somalia marks three decades since a dictator fell and chaos engulfed the country, the government is set to hold a troubled national election.

Or is it?

Two regional states refuse to take part, and time is running out before the February 8 date when mandates expire. A parliament resolution allows President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed and lawmakers to remain in office, but going beyond February 8 brings "an unpredictable political situation in a country where we certainly don't need any more of that," U.N. Special Representative James Swan said this week.

Amid the campaign billboards and speeches in the capital, Mogadishu, is a sense of frustration as people are urged to support candidates but again cannot directly take part.

"Nobody has ever asked us what we want or whom we would choose as president," said Asha Abdulle, who runs a small tea shop.

"Every president wants to extend his tenure and at least add one more year, so why can't they make it official and hold elections every five years instead of four?" wondered Abdirisaq Ali Mohamed as he watched TV at a hotel.

The uncertainty is ripe for exploitation by the Somalia-based al-Shabab extremist group, which has threatened to attack the polls. Meanwhile, the country is adjusting to the withdrawal of 700 U.S. military personnel, completed in mid-January.

A successful election means Somalia's government can move on to address urgent issues like the COVID-19 pandemic, a locust outbreak and hundreds of thousands of people displaced by climate crises such as drought.

Despite its insecurity, the Horn of Africa nation has had peaceful changes of leadership every four years since 2000, and it has the distinction of having Africa's first democratically elected president to peacefully step down, Aden Abdulle Osman, in 1967.

But the goal of a direct, one-person-one-vote election in Somalia remains elusive. It was meant to take place this time. Instead, the federal government and states agreed on another "indirect election," with senators and members of parliament elected by community leaders — delegates of powerful clans — in each member state.

Members of parliament and senators then elect Somalia's president.

Opposition leaders and civil society groups have objected, arguing it leaves them no say in the politics of their own country.

Now the regional states of Jubbaland and Puntland have refused to take part, objecting to issues including how electoral management bodies should be appointed and delegates selected. That includes delegates from the breakaway region of Somaliland, which considers itself an independent country though it is not internationally recognized.

Jubbaland and Puntland finally appointed electoral commissioners late this week, a sign of progress.

"No partial elections or parallel processes," the U.S. Embassy said as it encouraged political leaders to meet on remaining issues. On Saturday, Somalia said the president assured the international community he was willing to "fulfill free, fair and transparent elections."

The opposition alliance, which includes two former presidents and former Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khayre, has urged the president to let all stakeholders play their rightful roles in the election.

"You promised that once president you will be a good Somali elder. You were given to lead a united people in a peaceful way," said one former president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. He himself benefited from an extra year in office when elections were not ready.

He also warned that Jubbaland and Puntland could go the way of Somaliland, with Somalia's unity at stake.

"There's no way that Somalia will go back to the 1990s," Mohamud said of an era in which local warlords ran rampant in Mogadishu and an attempt by the U.S. military to intervene collapsed when the bodies of its soldiers were dragged through the streets.

The objecting states have been given plenty of time to take part in the election, said Ibrahim Hassan Haji, an electoral commission member from Southwest state.

"Otherwise, we will be forced to go ahead without them and select their quotas of [delegates] from here in Mogadishu," he said.

But the head of the local Hiraal Institute think tank, Hussein Sheikh Ali, said holding a partial election would not be tolerated in a country where clans are still "armed to the teeth."

Instead, "it is always the 'sixth clan' [the international community] that intervenes" in such crises and a road map is usually agreed upon, added political analyst Liban Abdullahi.

The U.N. special representative, however, said any resolution must come from Somali leaders, whom he urged to "be imaginative." He would not say how the international community might respond to a vote that goes ahead without all states involved.