Nafisa heard the sound of a woman singing. It was a call for the Janjaweed militiamen to attack.

This kind of singing had ushered in other conflicts in the Darfur region of Sudan, but this was different.

"Before they had spears and knives," Nafisa said. "Suddenly they had Kalashnikovs and heavy weapons we had never seen before."

The Janjaweed swept through the village on horseback burning crops, homes and the people inside.They had orders to exterminate farming communities.

"My husband and two sons were set on fire," she added. "So I hid until I could run to another village where the burning hadn't reached."

Her third son, Tayib, was not home. He survived and fled with his mother. This was in 2003, and it was the first of four times they have now been displaced by violence.

The last time was only two months ago, here in Libya. A week after Nafisa arrived, forces from the east attacked the western capital, Tripoli, and Nafisa fled the bombing.

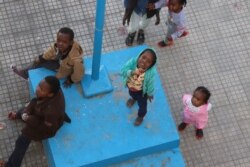

Now, she lives with other people who have survived mass murders, rapes, wars and gang violence in Sudan, Eritrea and other countries. They stay in a schoolhouse that was converted into a displacement camp for people fleeing the Tripoli clashes.

"When the war erupted here we had no other choice than to run out through the rubble," she said.

The Journey

When the "burning" reached the next village, Nafisa and her son fled to a massive camp for displaced families in Sudan called Kalma, where roughly 90,000 people still live.

But the conflict followed them and Kalma remains a notoriously dangerous place to live.In April, 16 people were killed in clashes there.

Nafisa and Tayib walked out of Sudan into Chad, where they caught a ride and spent 17 days in the desert on their way to Libya. They crossed the border and made their way to Umm Al Aranib, a town in Libya's volatile southern desert.

While resting in a garden in Umm AL Aranib, Tayib and some other young men were surrounded by armed militants and forced onto the back of a truck, where they were tied up. Parents were told they needed to pay ransom if they wanted their sons back alive.

Nafisa and other parents begged friends, relatives and strangers for money, and she eventually raised about $3,500 to secure Tayib's release.

"He was tortured," she said." The boys were burned with fire and chained up. There were many from Darfur locked up there."

A week later, in the city of Sabha, Nafisa found a ride to Tripoli, a breezy Mediterranean city that, in March, was at peace. After 15 years of running, she thought she could stop. But now she lives in limbo, having applied for asylum in Libya with no real desire to stay and wait out another war.

"Sudan and Libya are the same," she said." I want to go to Europe."

The Next Stop?

All the Sudanese people staying in this schoolhouse, like Nafisa, share the same hope of finding a way to Europe.

Libya is known as a gateway to Europe from Africa, where a vast network of smugglers send boats into the sea, in the hopes of reaching Italy. The boats are often ill-equipped, overcrowded and deadly.

Nearly 550 people have died trying to cross the Mediterranean into Europe this year alone, according to the International Organization for Migration. By the end of the year, that number is expected to be in the thousands.

But between abject poverty and increasing violence, Nafisa says she has no future in Libya and the Darfur she grew up in is gone. When she was a child, men that now serve as Janjaweed soldiers were nomadic herders, who traveled through the northern farming areas only during the rainy season.

"Sometimes there were tensions when the animals would graze on our farms," Nafisa explained." And sometimes they would give us milk or meat and we would give them watermelons and sorghum."