For decades, Christine Uwimana was unable to complete any documents requesting the name of her father. Either she left the space blank, mirroring her uncertainty, or she inserted the word “unknown.” Nor was she able to conjure up much more than the name of her biological mother, from whom she was taken as an infant in Rwanda.

Now, at 48, Uwimana finally can supply the name of her father, Godefroid Nyilibakwe. She also has more details about her mother, Agnes Kabarenzi.

Her newly completed family tree is “the most distinguished diploma I have ever had,” said Uwimana, a psychiatrist in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Both of Uwimana’s biological parents died in prison following a 1973 military coup in Rwanda. Details about their lives and deaths have emerged as part of a VOA Central Africa Service radio series examining the coup and the relative silence enshrouding its victims.

At least 56 people allegedly perished in the coup’s aftermath, according to an Amnesty International report, and an official charged with notifying their families after a Rwandan court ordered the government to provide financial compensation for their deaths.

But that notice did not come until 1985. Meanwhile, relatives were banished from the capital, Kigali, and kept uninformed and in limbo for years. People were too fearful to publicly discuss the disappearances.

Airing secrets

“Rwanda 1973 — Untold Story” penetrated that silence late last year, with 22 hourlong episodes. The Kinyarwanda-language series recounted events leading from that July 5, when army General Juvenal Habyarimana seized power from Rwanda’s first elected president, Grégoire Kayibanda.

An ethnic Hutu from the north, Habyarimana led the country — first under military rule and, as of 1978, as president — until his plane was shot down in April 1994, an act widely blamed for triggering the genocide in which Hutu extremists killed an estimated 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and their sympathizers.

Kayibanda was arrested, along with dozens of others, mostly politicians and senior military officers. The series explored their likely fates: At least 15 reportedly were executed by gunfire within a few months. At least five more allegedly were killed during suspicious nighttime prison transfers. Another 20-some lingered for up to three years before starving to death.

Victims’ widows and children spoke of their own suffering to the program’s host and researcher, Venuste Nshimiyimana. He interviewed the lone man known to have survived, Antony Muganga, plus dozens of other people with firsthand knowledge of events, including a few former officials in Rwanda’s military and judiciary at the time. He solicited listeners’ questions and tips, including the locations where bodies allegedly were dumped.

Their contributions cast light on a shadowy chapter of Rwandan history, creating an opening for more discussion and investigation, said James Gasana, a former Rwandan politician who listened to the VOA series.

“Many people knew” about the killings, said Gasana, 70, who has written a book about later events leading up through his time as a Rwandan cabinet official in the early 1990s.

Because crimes largely went unacknowledged and perpetrators were not held to account, “it became a huge fracture, a huge crack in our society,” Gasana told VOA from his home in Switzerland. “Justice which is not rendered — that’s a huge problem.”

Taken prisoner

Nshimiyimana devoted one episode to Kabarenzi, one of two women taken prisoner soon after the coup. (The other reportedly survives.) At the time of her arrest in early July 1973, Kabarenzi was a 24-year-old social worker in Kigali’s Centre Hospitalier. The reason for her arrest was unclear, though it may have been through association with Godefroid Nyilibakwe, her sister’s husband and a labor ministry official in Kayibanda’s administration.

Six months after Kabarenzi was arrested and sent to a Kigali prison, she gave birth to a baby girl at the hospital where she had worked. She refused to name the father. A week later, the baby was taken from Kabarenzi and given to another woman to raise.

The next month, in February 1974, the coup inmates were transferred to prisons in Gisenyi and Ruhengeri. Kabarenzi was among more than 20 sent to Ruhengeri, also known as Musanze, capital of Rwanda’s Northern Province.

At Ruhengeri, the coup inmates were beaten and tortured with electric shocks, two other men who were imprisoned at the same time told VOA. Finally, sometime in September 1976, they began a hunger strike to protest their treatment.

After a few days, the inmates tried to abandon their hunger strike, but prison authorities refused them any food, witnesses told VOA. They said the inmates, unable to see each other from their respective cells, prayed aloud and sang hymns together for comfort and spiritual sustenance. But as starvation took its toll, the chorus began to fade. The first of the hunger strikers died on day 34. The last to succumb, on day 52, was Agnes Kabarenzi.

“I didn’t know how she had been tortured or mistreated. … I didn’t know that she lived in hell for another three years after my birth,” Uwimana told VOA in a phone interview.

In fact, Uwimana had known very little of her mother. Sleuthing by VOA’s Nshimiyimana would change that.

A search for family history

While researching Kabarenzi, the journalist learned of her baby girl and determined to find out what had happened to her. Working from his home in London, he followed a trail that eventually led to the adult Uwimana in Switzerland. By then, it was late September, and she had begun listening to the series.

She told Nshimiyimana of growing up in Gitarama, a central Rwandan city now known as Muhanga. Anastasie Nyirahabimana had provided a loving home and, with her husband, a younger sister who now lives in Belgium.

“She’s a hero — someone wonderful, with lots of love,” Uwimana said of her adoptive mother.

Both parents are deceased, and the sisters remain close.

“I grew up knowing that Christine is my elder sister, and I still believe so,” Bernadette Tuyishime told VOA on the program.

The family encouraged Uwimana’s education, and she pursued a degree in psychiatry in Rwanda. She moved to Switzerland in 2006 to continue her professional studies at the University of Geneva, later working in hospitals and, as of several years ago, in private practice in Lausanne.

Over the years, Uwimana craved information about her biological parents. In 1985, as an adolescent, she got the sparest of details about Kabarenzi, including the news that she was dead.

“I only knew her name. I had seen her picture. I had heard she was intelligent, kind. C’est tout,” Uwimana said.

As for her paternity, Uwimana had three theories: an unnamed fiancé, an unknown lover or a particular government official. She once asked a relative of that official to consider genetic testing but was turned down.

Uwimana shared her suspicions with Nshimiyimana, who already was investigating. The journalist persuaded the relative, now living in France, to submit to a cheek swab for DNA testing, as did Uwimana. By late October, a Swiss hospital’s forensic genetics unit had results indicating a close match. The two almost certainly had the same father — former labor ministry official Godefroid Nyilibakwe.

Like Uwimana’s mother, Godefroid Nyilibakwe is believed to have died at Ruhengeri prison, though the exact date and cause of death are unknown.

“I know his name now,” said Uwimana, who became the centerpiece of the series’ December 6 episode. In it, the genetic findings were disclosed.

Breaking free of taboo

Uwimana later thanked VOA for providing a forum in which “to talk about things that were taboo. You allowed many people to open up and talk. From there, you managed to give me back my parents.”

Albert Bizindori, who leads a support group for people whose parents were killed in the coup, told VOA in the December 20 episode that “the joy that you brought to Christine was for all of us.

“For 47 years, everything was done to keep our parents in the darkness, hoping they would be forgotten,” he said. “But thanks to VOA, all Rwandans now know that they were unlawfully killed. They are part of Rwanda’s history.”

Bizindori has recommended bringing together relatives of the victims and their alleged torturers to confront the past — as an exercise in healing, not vengeance. He said further exploring that history could “lead to a genuine reconciliation and unity.”

Others have suggested erecting a memorial to the victims.

“I would ask the government to build a memorial for them … a place to put flowers,” said Clarisse Kayisire, a listener in Ottawa, Canada. She left Rwanda at age 24, just before the 1994 genocide that claimed some of her own relatives. She said it was important to address uncomfortable truths. “We have to say it, even if it’s not good.”

Uwimana is mindful that her paternity results may discomfit her blood relatives.

“I don’t want to create any jealousy,” she emphasized, but added that she would welcome more details about Nyilibakwe, such as where he was born, grew up and studied.

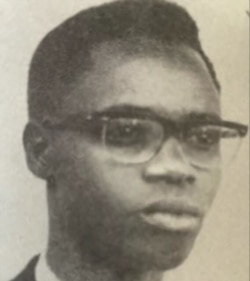

Meanwhile, Uwimana has found a published photograph of the man, which she cut out and taped into a frame. It is on display for her blended family — three children from her first marriage and three stepchildren with her partner, Marc Pidoux, an educator.

Her biological children — two daughters and a son, ranging in age from 12 to 17 — “have always asked me who was my father,” Uwimana said. “They have been able to complete now our family tree. That was the missing part. …. My story is complete now.”

Central Africa Service chief Etienne Karekezi contributed to this report and also edited the radio series.