A foiled coup in the Ethiopian state of Amhara that left five senior officials dead, including the army's chief of staff, has thrust ethnic militias in one of Africa's fastest-growing economies into the spotlight.

The two attacks on Saturday night were led by Amhara's head of state security General Asamnew Tsige, who had been openly recruiting fighters for ethnic militias in a state that has become a flashpoint for violence.

Militias formed by ethnic groups are proliferating across Ethiopia, threatening sweeping political and economic reforms that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed kickstarted after he took power in the Horn of Africa country in April 2018.

Why are militias emerging?

Ethiopia's 100 million citizens come from dozens of ethnic groups with competing claims to land, resources and influence.

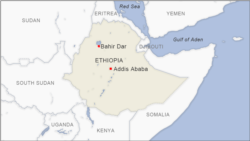

The country's federal government based in the capital Addis Ababa oversees nine ethnic-based regional states, which have autonomy over their revenues and security forces.

The governing EPRDF coalition that seized power in 1991 was dominated by the minority Tigrayans, who make up about 6% of the population. The government kept a lid on bubbling tensions for decades by quashing virtually all dissent, including expressions of ethnic nationalism.

But in 2018, Abiy's predecessor resigned after three years of widespread anti-government protests. Abiy was selected by the EPRDF as its leader and his government prosecuted security officials accused of past abuses, lifted bans on some separatist groups and released thousands of political prisoners.

Local leaders are now taking advantage of the new freedoms to build ethnic power bases. Groups that felt excluded in a system once dominated by Tigrayans are flexing their muscles.

Some Tigrayans and other regional power brokers also feel victimized by Abiy's personnel changes, especially his shake-up of the military and intelligence services.

What do they want?

Since Abiy embarked on his ambitious reforms, old state border disputes have reignited. Large ethnic groups that dominate in many regions are demanding more territory and resources. At the same time, smaller groups, tired of being sidelined, are pushing back.

While Ethiopia's constitution guarantees all ethnic groups the right to a referendum on self-determination, the government has long forbidden such votes. The southern Sidama people, for example, are now demanding one.

How widespread is the problem?

The latest round of violence began in Oromia, Abiy's home region and the hotbed of the protests that propelled him to power. A surge in killings there last year forced mass displacements of people.

Violence in other regions followed, including in Amhara which has border disputes with two of its neighbors. Many in the Tigray region are also now hostile to the federal government.

New York-based Human Rights Watch has reported ethnic killings in the Harari and Somali regions of Ethiopia too.

How bad is the violence?

Ethnic militias are committing vigilante violence, killing local government officials, burning homes and raping women, according to Addis-based officials, diplomats and aid workers.

Such attacks have driven some 2.4 million Ethiopians from their homes, the United Nations says.

In one of the worst recent attacks, about 200 people were killed in tit for-tat violence in May in the Benishangul-Gumuz region near the border with Sudan.

Displaced people in southern Ethiopia told Reuters they had fled Oromo youth armed with knives and firearms. The family of a coffee farmer said a mob chopped his limbs off before hanging his body from a tree.

Ethnic killings have also been reported on university campuses in Tigray and Amhara as students turned on students, university administrators say.