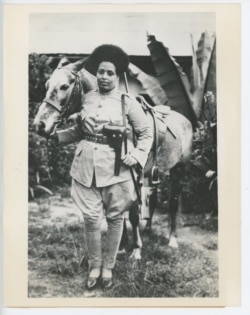

When novelist Maaza Mengiste began researching the Ethiopian resistance to the 1935 invasion by Italian forces, she came across photographs of women dressed in military attire with rifles slung over their shoulders. As she organized them by date and location, she began to build a picture of the conflict she never learned about in school.

“These women decided to join in the front lines,” Maaza told VOA. “I had never heard that story. And this is what really inspired me to continue this, because if I didn’t know it, and if a lot of other Ethiopians weren’t speaking about it, this means maybe that nobody really had been paying attention to this.”

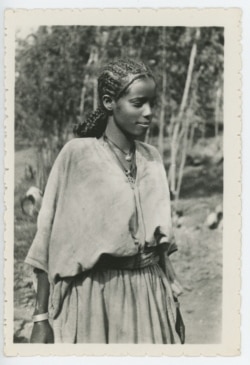

As Maaza kept digging, she found photographs of Ethiopian girls taken as mementos by Italian soldiers. Some photos were used to entice men to join the conflict. Others were much darker and showed the horror of war.

“Those photographs showed the extent of that brutality,” she said. “And those were photographs not taken by journalists. They were taken by soldiers for fun, and they were passed around as jokes and as postcards to send home. And that was the side of war also that I wanted to show.”

The research inspired her novel “The Shadow King.” It tells the story of Hirut, an orphaned and mistreated girl who becomes the personal guard for a person pretending to be the exiled King Haile Selassie. The novel, her second, has won international acclaim and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.

“It’s a book that works for many different people in many different ways,” Kamila Shamsie, an award-winning Pakistani novelist, said in a video trailer promoting Maaza’s book (Kamila Shamsie on Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King). “Maaza is doing things with history that hadn’t been done before. She’s putting women into that story in a way that’s really compelling. It’s very intelligently structured. It’s beautifully written.”

Maaza was shortlisted alongside Zimbabwean author Tsitsi Dangarembga, who was arrested for participating in anti-government protests against corruption during the time of her nomination. Dangarembga’s recent novel, “This Mournable Body,” looks at the everyday struggles of Zimbabweans.

Maaza’s book revisits part of forgotten history, said Lee Child, an author of 24 novels and among the judges for the 2020 Booker Prize.

“The story is important, really, the opening shots of the Second World War, but rarely told before. And the whole is wrapped in gorgeous lyrical prose at the highest quality,” Child said in a video discussing the novel. “Its place on the shortlist merely confirms its status as one of the great novels of the year.”

Maaza said she was not a natural novelist. Born in Ethiopia in 1971, her family fled the brutal Derg regime when she was 4 years old. The family spent time in Nigeria and Kenya before relocating permanently to the United States.

As a girl, she recalled memories of her first years in Ethiopia. But it wasn’t until she was much older that she considered writing them down.

“I’m surprised I kept those memories, because I was very young,” she said. “But I think that the shock of what I experienced both in Ethiopia but also the migration was so intense and so deep that everything froze for me and stayed inside. And so, I would keep coming back.”

And even though her decision to pursue writing wasn’t immediately welcomed by her parents, she felt she had stories bursting within her. She believes other Ethiopians feel the same but do not necessarily have an avenue to share their stories with the world.

“Across East Africa, history and literature is told orally,” Maaza said. “And I think all of us remember those moments when we are sitting around at a dinner table or sitting having a meal and someone starts a story. And the entire room moves in that direction. Everyone is laughing, or people are crying. That’s a book inside a human being. And my inspirations came from my relatives. Some of them didn’t go to school.”

Now, she wants to open the door to new authors. She has edited a collection of stories by 14 Ethiopian writers called “Addis Ababa Noir.” She believes there is a lot of talent that could be shared with a wider audience with the help of translators and publishing companies.

Over the next year, Maaza plans to hold workshops to train translators, editors and writers of fiction and nonfiction.

“That is an imperative task in front of us now because there is talent in Ethiopia, and we don't have enough translators to cross over,” she said.