For Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, who comprise more than 40% of their country’s population and most of the people in the Tigray region, the city of Axum is the holiest of places.

They believe it to be home to the Ark of the Covenant, or the original Ten Commandments, and the birthplace of Ethiopian Christianity.

“I would die to protect this church,” said Alem Gebreslase, a 24-year-old parishioner, on Sunday at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, one of the oldest churches in Ethiopia and Axum’s center or worship. “But God will protect the Ark.”

In past years, pilgrims and tourists would flock to Axum to pray, visit historical sites and snap pictures. Last year, when the coronavirus pandemic swept the world, most stayed away. Then in November 2020, war broke out and visitors stopped coming almost completely.

The war, primarily between the Ethiopian National Defense Force and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, includes Eritrean forces fighting against the TPLF, and militias on both sides.

The violence began in November 2020 when TPLF forces attacked federal military bases in Tigray and Ethiopian forces swept through the region.

In the first month of conflict, Eritrean troops killed hundreds of civilians in Axum, according to Amnesty International.

In Axum, locals described those early days of violence, with details varying from mass shootings to house-to-house raids. Consistent in every person’s story, however, were descriptions of so many bodies.

“Besides the soaring death toll,” Amnesty International said in a February statement, “Axum’s residents were plunged into days of collective trauma amid violence, mourning and mass burials.”

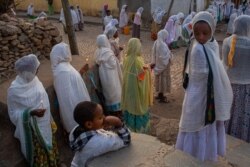

In recent months, Axum has quieted, with violence mostly taking place in the countryside. The city has also begun hosting different kinds of visitors. Families displaced by war in their villages and small towns have come in droves, crowding into empty schoolhouses and on the grounds of the church.

“The situation has become reversed,” said Aygdu, a 57-year-old Axum merchant who gave only his nickname for security reasons. “People were fleeing from the city to the countryside. Now they are fleeing from the country to the city.”

Along the roadsides in remote areas outside of Axum, hundreds of Ethiopian and Eritrean soldiers could be seen in trucks, buses and cars over the weekend. In the city of Axum, Ethiopian federal forces patrolled the streets, enforcing a strict nightly curfew.

In the churchyard early Sunday, a mother of five begged for small amounts of money, saying she just arrived in Axum the day before, when troops entered her town.

“I have no other place to go,” she said.

A city strained

At a restaurant in town that serves traditional Ethiopian food, beers and sodas, Aygdu, the merchant, said the influx of displaced families has forced people to open their businesses, despite sporadic violence.

The church and the schools appear crowded with displaced families, he said, but there are also many households hosting relatives, straining the budgets in a town that has been in economic free-fall for more than a year. Prices of basic food items have doubled, he added.

“We may feel it’s dangerous,” he explained, “But if we don’t open our shops, we may die from hunger.”

In the early days of conflict, locals say businesses, homes and public services were looted and hundreds of civilians were killed. Aygdu’s furniture supply store was looted along with his house, he said.

“Even my television and bed were taken,” he said.

Hospitals overwhelmed

Hospitals and health care centers across the region have also been looted, according to Axum University’s Referral Hospital’s administrative director, Zemichael Weldegebriel.

“We are trying to support poor communities,” he said in his office on Thursday. “But the health care we can provide is not meeting their requirements.”

His hospital, which is supposed to take the worst cases from an area where 3.5 million people live, he said, is now taking every kind of case, because most local health care centers were either damaged or robbed until their cupboards were nearly bare.

People are still dying from war injuries, he added, but mortality rates have also gone up for people who have never been victims of bombs or bullets. More women are dying in childbirth, more children are malnourished, and more injuries and sicknesses are fatal because of late or substandard care, he said.

Essential medicines are missing and agents to conduct medical tests are largely not available, he explained. Free replacement medicine is provided by the federal government, but he said local supply centers are mostly out of stock.

And the war wounded keep coming. “In seven months, we have never been out of patients,” he said.

In a ward filled with the wounded, Nigusse Tadele, 29, said he was hurrying out of the house as bombs drew nearer. A blast hit near him and his next memory was waking up at a clinic where his injured toes became infected before he could get to the hospital.

More than a month later, he has lost his toes and lays in a cot in Axum, waiting to recover and return to his work as a government agriculture worker, he said.

“They may suspect there are TPLF supporters in our village,” he said, considering why he was hit. “But I haven’t seen any military camp.”