Officials are gathering in Niger’s capital this weekend for an African Union summit that begins the “operational phase” of a long-sought continental free trade zone.

Some 50 heads of state were to arrive in Niamey on Friday, a day behind their foreign ministers, for Sunday’s summit on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). By integrating economies and reducing trade barriers such as tariffs, the pact aims to increase employment prospects, living standards and opportunities for the continent’s 1.2 billion people and to make Africans more competitive regionally and globally.

The trade deal got a boost earlier this week when Nigeria’s president, Muhammadu Buhari, committed to signing the deal this weekend. The West African nation of roughly 190 million people boasts Africa’s largest population and economy.

Africa “needs not only a trade policy but also a continental manufacturing agenda,” the Nigerian president’s official Twitter account quoted Buhari as saying. He previously had resisted the deal, even skipping last year’s AU meeting.

Two other nations in the 54-member AU bloc, Benin and Eritrea, have withheld support for the pact.

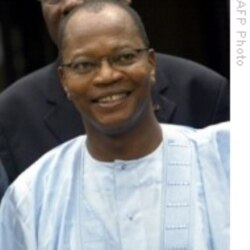

Nigeria’s willingness to sign the pact, along with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adoption of a common currency last week, will help boost trade throughout the continent, says Mohamed Ibn Chambas, the U.N. secretary-general’s special representative and head of the U.N. office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS).

“The continental free trade area will to a large extent also reinforce regional free trade areas,” Chambas told VOA. “And this is where a common currency comes in. If you have a free trade area and it is matched also by a regional common currency, the impact of course will be to boost both free trade and easy commerce within the area.”

Regional common currency

ECOWAS plans to introduce the ECO currency in 2020, though its debut has been delayed repeatedly since 2000.

The African free trade zone has been under discussion since 2002, with a draft deal signed in early 2018. In May, it surpassed a threshold of ratification by at least 22 member countries’ legislatures.

“And now the process of free trade can start,” said Ibrahima Kane, a Senegal-based senior program adviser with the Open Society Foundations.

A date of next July 1 has been put forward for trading to begin, but “saying that this treaty will be operational in 2020 is not realistic,” said Kane, who focuses on African Union matters. “People are still negotiating on a number of critical issues,” including rules of origin, which determine whether a manufactured product gets taxed or not.

Challenges, disparities

Kane cited other challenges, including disparities among African countries’ connectivity, infrastructure, customs and regulatory enforcement, payment systems and more.

“Many things will be done online,” he said. “How many countries have official borders? How many will be equipped with this kind of infrastructure? … African countries need to agree on standards. It’s a long, long, long process.”

AU and national leaders also are expected to decide Sunday where to locate the trade zone’s headquarters. Five countries are in the running for headquarters: Egypt, eSwatini, Ghana, Kenya and Madagascar. As Reuters points out, a country’s selection will bring it more prominence.

The pact is intended to improve circumstances for the whole AU bloc. Currently, intra-African trade accounts for 16% of exports, up from 5% in 1980 but “low compared to intra-regional trade in Europe and Asia,” according to the African Export-Import Bank.

Tariffs on intra-African trade average 6.1%, more than those levied on non-African countries, the French news agency AFP reported. It also cited an International Monetary Fund report that said “improving trade logistics, such as customs services, and addressing poor infrastructure could be up to four times more effective in boosting trade than tariff reductions.”