Researchers are warning of an emerging form of intestinal disease in sub-Saharan Africa. It’s targeting mostly HIV-infected people, who are not on treatment. The disease kills up to 45 percent of those infected.

The disease can be found in all corners of sub-Saharan Africa, according to Chinyere Okoro of Britain’s Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

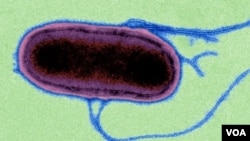

“It’s an invasive disease. It’s a disease that is found in the bloodstream and can invade other internal organs of the patient. It’s caused by a bacterium known as Salmonella Typhimurium. Incidentally, Salmonella Typhimurium in healthy individuals usually results in gastroenteritis, which one of the symptoms will be diarrhea. So, most people would not need extensive treatment or hospitalization of any of that,” she said.

But Salmonella Typhimurium, she said, causes an illness much less like gastroenteritis and more like typhoid in those with compromised immune systems.

“When I mean immune-compromised individuals, I mean people whose immune system is compromised by an existing disease. In this case it’s mostly HIV and in children, who are currently infected with [the] malaria parasite or are malnourished,” she said.

The disease progresses rapidly and can kill in a matter of days.

Okoro said that people, who are receiving antiretroviral therapy, or ART, for HIV infection, are less likely to become infected with Salmonella Typhimurium.

“With appropriate treatment, the individual’s immune system is not as compromised as would be required for the disease to take hold so to speak. So, if ART is available, we expect to see a reduce rate of transmission and incident rates as a result,” she said.

A DNA analysis of the bacterium shows it first emerged in two waves. The first occurred about 50 years ago in southeastern Africa, and the next about 35 years ago, possibly from the Congo Basin. These are similar to the routes taken by HIV.

Okoro said, at first, it was an opportunist infection attacking HIV-positive people. She says now it has found a home among those not on treatment.

Over the past decade, the disease was initially treated with the antibiotic chloramphenicol. However, the bacterium quickly built up a resistance to the drug. That contributed to the disease’s rapid spread among HIV-positive people.

Okoro said the disease can be treated with newer, more powerful and more expensive antibiotics where available.

“What this analysis actually does show very clearly is how pathogens can emerge rapidly given the right conditions and what needs to be done,” she said.

So, getting more HIV-positive Africans on antiretrovirals could help stem the spread of the intestinal disease. The same holds true for better malaria treatment and nutrition for young children.

The exact route of transmission remains unknown, however. Okoro said, right now, it appears the disease is not spread through the food chain.

The disease can be found in all corners of sub-Saharan Africa, according to Chinyere Okoro of Britain’s Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

“It’s an invasive disease. It’s a disease that is found in the bloodstream and can invade other internal organs of the patient. It’s caused by a bacterium known as Salmonella Typhimurium. Incidentally, Salmonella Typhimurium in healthy individuals usually results in gastroenteritis, which one of the symptoms will be diarrhea. So, most people would not need extensive treatment or hospitalization of any of that,” she said.

But Salmonella Typhimurium, she said, causes an illness much less like gastroenteritis and more like typhoid in those with compromised immune systems.

“When I mean immune-compromised individuals, I mean people whose immune system is compromised by an existing disease. In this case it’s mostly HIV and in children, who are currently infected with [the] malaria parasite or are malnourished,” she said.

The disease progresses rapidly and can kill in a matter of days.

Okoro said that people, who are receiving antiretroviral therapy, or ART, for HIV infection, are less likely to become infected with Salmonella Typhimurium.

“With appropriate treatment, the individual’s immune system is not as compromised as would be required for the disease to take hold so to speak. So, if ART is available, we expect to see a reduce rate of transmission and incident rates as a result,” she said.

A DNA analysis of the bacterium shows it first emerged in two waves. The first occurred about 50 years ago in southeastern Africa, and the next about 35 years ago, possibly from the Congo Basin. These are similar to the routes taken by HIV.

Okoro said, at first, it was an opportunist infection attacking HIV-positive people. She says now it has found a home among those not on treatment.

Over the past decade, the disease was initially treated with the antibiotic chloramphenicol. However, the bacterium quickly built up a resistance to the drug. That contributed to the disease’s rapid spread among HIV-positive people.

Okoro said the disease can be treated with newer, more powerful and more expensive antibiotics where available.

“What this analysis actually does show very clearly is how pathogens can emerge rapidly given the right conditions and what needs to be done,” she said.

So, getting more HIV-positive Africans on antiretrovirals could help stem the spread of the intestinal disease. The same holds true for better malaria treatment and nutrition for young children.

The exact route of transmission remains unknown, however. Okoro said, right now, it appears the disease is not spread through the food chain.