On a hilltop above the port city of Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos, Mohamed Eckberry sits on a bench in a pine forest with five other Afghan friends, escaping the heat of a sunny Mediterranean day.

“It's nice up here,” he says, reflecting on events of the last 20 days, since he leaving his Kabul home.

Eckberry is just 17. His parents weren't sure about him leaving. Would he be killed by smugglers, or drowned at sea? Afghanistan's never-ending war and their economic future also weighed heavily on their minds.

Eckberry, still in high school, was more sure than they were. “If I stayed in Afghanistan I cannot continue my education. I really have no future in Afghanistan. I want to study and continue my education here in Europe,” he said.

In the end, they gave him their blessing and he set out with five other friends for what he hopes will be a better life.

Mohamed Eckberry's friends are in their early 20s, a bit more worn in the face, and speak no English. But they sit calmly and listen while we talk. “Do you know anywhere we can go swimming?” he asks with teenage excitement that gives away his age. An odd question to ask sitting on a hilltop surrounded by the Aegean Sea.

A dangerous journey

Getting out of Afghanistan was not easy. Smugglers took him and 21 others across the border into Iran.

“They put 22 people in a small car, and they kept pushing and pushing us farther into the back," he recalls. "It was the worst experience of my life."

Crossing the border into Turkey only saw things get worse. Turkish police spotted them and took pursuit firing guns. The young men ran into the mountains and hid for three days.

“There was water because water was coming from the mountain," he says. "There was no food, bread — nothing and it was really cold at night. I thought we were going to die on that mountain.”

The 3-kilometer crossing from Turkey to Lesbos island didn't go much better. Smugglers pack as many as 60 people into a small rubber inflatable boat that is made to carry 10. The boats are usually underpowered with small inexpensive Chinese-made 15 to 20 horsepower outboard engines that have a high failure rate.

The smugglers do not get in the boats with the migrants. They designate someone to steer the boat with the outboard engine, point out a direction on the horizon, or a light in the distance at night, and send them off. Parts of the eastern coastline of Lesbos island are littered with abandoned rubber boats.

Eckberry told us he and his friends were in a boat with about 50 people. Halfway across, the motor was swamped with water and failed. “The waves were really high and we thought we were going to die in the middle of the sea. We kept drifting.” Finally they were spotted by the Greek coast guard and brought to Lesbos.

North into Europe

The food in the migrant camp on the outskirts of Mytilene was not to their liking, so Eckberry and his friends left to buy ferry tickets to Athens at the travel offices in town. Each morning, hundreds of migrants line up in front of the offices, pouring into the street, dodging traffic. The first person in line is usually squeezed hard against the office door by the constant pushing from people behind.

The ferry to Athens is large, about the size of a small cruise ship, but sells out fast every day. After four hours in line, Mohamed Eckberry and his friends were able to buy a ticket for the following day.

That evening's ferry was sold out.

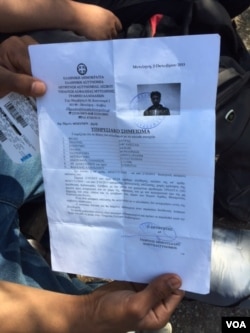

He proudly pulled his ticket and registration papers from his pocket to show VOA. The registration, with his picture on it, is written in Greek. He asks, “is this good for all of Europe?”

Having spent all their money on ferry tickets, the group considers returning to the camp for free food. Reminded that they will need a lot more money to continue their journey northward to Europe, they resolve to buy a somewhat decent meal anyway.

“We will have our relatives wire more money to a bank in Athens," says an optimistic Eckberry, his youthful enthusiasm coming through. "We are not going back now!”