Broad international recognition remained elusive for the Afghan Taliban in 2022. After more than a year in power, no foreign nation has officially recognized the Taliban government, although China, Russia, Pakistan and Turkmenistan have accredited Taliban diplomats.

Despite the Taliban’s desire for more engagement with the world, the country’s de facto rulers have continued their hardline policies, forbidding education for girls and dismissing calls for more inclusivity and less repression.

This month, Taliban deputy spokesperson Bilal Karimi told local media, “The policy and stance of isolation, and the creation of distance, has not brought any good results.”

While many support not isolating the Taliban for fear of a larger crisis, others question whether international engagement with the hardline regime will help improve conditions for the Afghan people.

Foreign demands on Taliban leadership

The United States, the European Union and the United Nations have all insisted the Taliban form an inclusive government, enact laws protecting human rights – especially women’s rights – and ensure Afghanistan does not become a base for terrorists to target other countries.

The group has shown some willingness to crack down on terrorist groups such as Islamic State, but leaders of terror group Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan operate in Afghanistan while fighters mount almost daily attacks on Pakistani security forces.

And the U.S. drone strike that killed al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in an upscale Kabul neighborhood last July cast serious doubt on the Taliban’s commitment to opposing global terrorism.

Beyond the Taliban’s ties to militant groups, their government’s repressive and hardline domestic policies have drawn criticism. Along with increased restrictions on women and girls, a clampdown on protests and curbs on press freedom – including a ban on VOA’s TV programs and FM broadcast transmissions in the country – the Taliban recently brought back public executions and floggings, a hallmark of their previous tyrannical rule in the late 1990s.

The Taliban are unrepentant about the practice. After the German mission for Afghanistan — now based in Doha and Berlin — described the public beatings as “a heinous violation of human dignity,” Taliban foreign ministry spokesperson Abdul Qahar Balkhi pointed to Germany’s Nazi past and accused the mission of “spearheading racism and Islamophobia.”

Taliban behavior no surprise for Afghan activists

Speaking to VOA, Afghan rights activist Parasto, who requested that only one name be used for safety reasons, questioned why the world believes the Taliban will soften under international pressure, given the group’s history of repression and ruling by decree.

“I really don't understand why is the world changing its behavior towards the Taliban. That it is not the first time that we are having the Taliban on the ground. It is the second time,” she said.

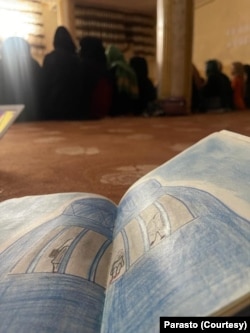

Parasto helps run a network of underground schools and believes the Taliban do not intend to let young girls go back to school. She said they are “just playing with words” when they say they are looking for a safe and religiously acceptable way to get girls to school.

The Taliban have banned girls from attending the 7th through the 12th grades since coming to power. On March 23, they opened most girls’ secondary schools but closed them after a few hours, drawing global condemnation. The Taliban said they would not bow to international pressure.

In December, the de facto rulers ordered public and private universities across the country to immediately suspend female students’ access to higher education until further notice.

Some in Afghanistan, however, have argued for a more cohesive international strategy for engaging with the Taliban.

“Some outright reject them [the Taliban]. Some believe … that a certain sensible leadership can emerge among the Taliban and then lastly there is a group that’s like us, who believe that unless [if] they truly want change, they will have to help us work on the larger population of Afghanistan,” said Obaidullah Baheer, a university lecturer and rights activist.

Baheer said he believes the Taliban’s victory over the U.S.-led coalition in Afghanistan has made the Taliban “stubborn.” He suggested that for now, the U.S. and its allies should set aside larger issues such as inclusive governance and constitution-making and focus on alleviating the day-to-day misery of the Afghan people.

In a recent Gallup survey, 98% of Afghans rated their living conditions as “suffering” under the new regime. More than 65% of the country’s population are in need of humanitarian assistance.

The Taliban blame financial sanctions, asset freezes and the reduction in foreign development aid for the crisis.

The case for engagement

Former U.S. Ambassador Robin Raphel has participated in back-channel diplomacy with the Taliban for decades and favors quiet engagement.

“The more we publicly harangue them on these issues, the longer it's going to take for the reality of the, of the desires of the Afghan people to have an effect on the Taliban,” said Raphel.

In a rare show of moderation, Taliban Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai expressed support for girls’ education earlier this year at a public event in Kabul, saying, “there is no Islamic prohibition for girls’ education.”

Such breaks from the Taliban leader’s ideology are rare and discouraged. “Cohesion is the value that's prized above all,” Raphel explained.

The U.S. has tried to strike a balance by releasing some funds to alleviate Afghans’ suffering, while not validating the Taliban as a legitimate government. Washington has donated more than $1 billion to Afghanistan through aid agencies since withdrawing troops last year, but also imposed new visa sanctions this year on current and former Taliban members for involvement in repressing women.

In a written statement, the U.S. Department of State told VOA, "We remind them constantly that their behavior toward the Afghan people will define our relationship with them. We cannot have a normal relationship with the Taliban until they respect the human rights of all Afghans.”

“First and foremost, the Taliban are accountable to the Afghan people," the State Department said.

At a regional conference of national security advisers held in India this month, Uzbek National Security Adviser Victor Mohammadov was quoted in Afghan media as saying that leaving Afghanistan alone to deal with the social, economic and humanitarian crisis, “will lead to increasing poverty in the region which we are already feeling ourselves.”

Baheer, who helped run the “Let Afghan Girls Learn” campaign this year, believes the Taliban will change only with sustained pressure from within the country and hoped the international community will provide greater support to local activists like him.

“At the end of the day the solution to Afghanistan is inside Afghanistan. ... It's just about time that the international community realizes that and helps us make the Taliban realize that,” he said, adding that if the Taliban don’t cede any space, “they will eventually be met with resistance. That has been the history of Afghanistan and the Taliban. We need to learn from it.”

Currently, more than 300 young girls are studying in six underground schools Parasto helped set up. Another 250 women who were forced to be illiterate when the Taliban were first in power are also learning to read and write there. She believes the financial and travels sanctions on the Taliban are not strong enough.

As international charities work to help Afghans deal with hunger and poverty with assistance largely supplied by the U.S. and its allies, calibrating how to pressure the Taliban without pushing Afghans into more misery remains a challenge.

Even the Taliban’s long-time supporter, Pakistan, is showing signs of fatigue with the group’s hardline stance. Last month, Pakistani Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari said Islamabad would not recognize the Taliban without global consensus, adding, “The world is running out of patience” with the group.