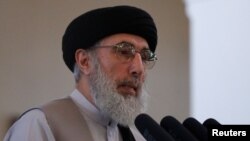

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hizb-i-Islami party is preparing to place thousands of fighters in Afghanistan's security forces, in one of the most complex parts of last year's peace deal between the Western-backed government and the former insurgent warlord.

Hizb-i-Islami has drawn up a list of 3,500 members of its militia for vetting and has handed over 80 names, mostly senior officers, to a special commission set up to oversee the integration, said Karim Amin, one of Hekmatyar's closest aides.

The move was agreed upon under the terms of the peace deal that brought in Hekmatyar, notorious for his forces' indiscriminate bombardment of Kabul during the 1990s civil war, after years of armed opposition.

While Hizb-i-Islami played little part in combat in recent years and ceased all operations since the accord, thousands of its fighters have not been disarmed, said Ahmad Farzan, the official in charge of overseeing implementation of the agreement.

Officials said the 80 names handed over were mainly those of older commanders who might be put on the payroll but who would probably go onto the inactive list.

Vetting is vital

Younger fighters present a bigger problem. Strict vetting is intended to weed out fighters who could pose an internal threat; in the first two months of 2017, at least a dozen "insider attacks" took place where service members turned on their colleagues.

Defense Ministry spokesman Dawlat Waziri said there would be no problem integrating Hizb-i-Islami members, provided they met selection criteria.

"Joining the national army is voluntary and anyone eligible who meets certain criteria can join to serve, and that includes Hizb-i-Islami members," he said.

However, the process, involving formal lists of fighters to be included in the army and police, goes beyond personal decisions to enlist. There is the question of how to integrate members of a militia who refuse to disarm and retain strong, personal loyalty to their leader into a NATO-trained force intended to represent the nation as a whole.

"They can be enrolled in the army, but the concern is that these guys will always be Hekmatyar's forces," said a senior official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The issue illustrates wider challenges facing the government as it seeks to implement an agreement with former insurgents that it hopes will pave the way for a broader peace deal with the Taliban, Afghanistan's dominant insurgent group.

No quiet transition

Hekmatyar, who has called for the constitution to be amended and said President Ashraf Ghani's government was not working, has already made it plain since his return to Kabul last week that he would not simply blend in quietly.

In public remarks, he called the Taliban his "brothers" and urged a peace agreement with them that would get foreign forces, which train the Afghan army, out of Afghanistan.

Amin went further this week, saying in a television interview that all combatant deaths in the war, including Taliban, should be referred to as "shaheed" or "martyred," a term currently used by the government only for its own forces and civilians.

While the Kabul government and its Western partners agree that only talks with the Taliban will end fighting, Hekmatyar's sympathetic stance risks complicating his militia's integration into forces that lost 6,785 killed last year fighting militants.

The Hizb-i-Islami militia's refusal to disarm suggested continued mutual suspicion between former insurgents and the government.

"No one can guarantee that if a commander puts down his weapon, he would survive," said Hizb-i-Islami spokesman Qareem ur Rahman. "They can't put down their weapons, but they won't fight against the government."